“Mean is the man, M—N is his Name”

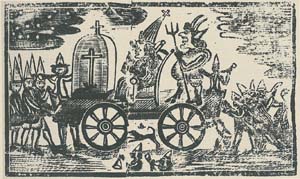

This is the Fifth of November, which Bostonians of the mid-1700s celebrated as “Pope Night.” Young men and boys would parade with what they called pageantry and we’d call floats: wagons decorated with giant puppets representing the Pope, the Devil, and political enemies of the day.

In 1769, the 5th was a Sunday, so Pope Night was piously observed on 6 November. Here’s a description of the pageantry from the 13 November issue of the Boston Evening-Post:

Mein was also an immigrant, a Scotsman, and an associate of the Rev. Robert Sandeman, who had established a new sect of Protestantism in New England. All those things caused most Bostonians to view him with suspicion. He responded by mocking the local Whigs’ heroes, needling their sore spots, and exposing their hypocrisies.

On 29 Oct 1769 that conflict had come to a head as Mein got into a fight on the street with several Boston merchants. He fled to a British army barracks for protection and then went into hiding. Mein’s partner, John Fleeming, continued to put out their Chronicle newspaper, but Mein would soon leave Boston forever. And, judging by the Pope Night poem, not many locals missed him.

There will be more about Mein—how he had attacked another printer physically, and how John Hancock managed to put him out of business—in my talk at the Boston Public Library tomorrow evening. Come by and hear lots of gossip from “Boston’s Pre-Revolutionary Newspaper Wars.”

In 1769, the 5th was a Sunday, so Pope Night was piously observed on 6 November. Here’s a description of the pageantry from the 13 November issue of the Boston Evening-Post:

Description of the POPE, 1769.Who was John Mein, whose name was spelled out in that acrostic? He was publisher of the Boston Chronicle, the most vociferous pro-Crown newspaper in Boston.

Toasts on the Front of the large Lanthorn.

Love and Unity. — The American Whig. —

Confusion to the Torries, and a total Banishment to Bribery and Corruption.

On the right side of the same. —An Acrostick.

J nsulting Wretch, well him expose,

O ’er the whole World his Deeds disclose,

H ell now gaups wide to take him in,

N ow he is ripe, Oh Lump of Sin.

M ean is the Man, M—N is his Name,

E nough he’s spread his hellish Fame,

I nfernal Furies hurl his Soul,

N ine Million Times from Pole to Pole.

Mein was also an immigrant, a Scotsman, and an associate of the Rev. Robert Sandeman, who had established a new sect of Protestantism in New England. All those things caused most Bostonians to view him with suspicion. He responded by mocking the local Whigs’ heroes, needling their sore spots, and exposing their hypocrisies.

On 29 Oct 1769 that conflict had come to a head as Mein got into a fight on the street with several Boston merchants. He fled to a British army barracks for protection and then went into hiding. Mein’s partner, John Fleeming, continued to put out their Chronicle newspaper, but Mein would soon leave Boston forever. And, judging by the Pope Night poem, not many locals missed him.

There will be more about Mein—how he had attacked another printer physically, and how John Hancock managed to put him out of business—in my talk at the Boston Public Library tomorrow evening. Come by and hear lots of gossip from “Boston’s Pre-Revolutionary Newspaper Wars.”

8 comments:

I'm no expert on these matters, but it seems that Mein was not only an interesting colonial figure, but that his relationship w/ J. Hancock was also quite interesting. The latter is important b/c it harkens back to a proposition made by yourself several months ago, that JH was virtually unknown to Europeans before the Decl'n of Independence. But Mein, himself, almost singlehandedly ensured that London(at least) knew who JH was, and on two different fronts:

John Mein fled Boston in '69 or '70 for England and apparently spilled his guts to Lord Dartmouth about Patriot activities immediately upon arrival. Hancock must have been mentioned. I think it is this same Lord Dartmouth who was the President of the Board of Trade (London), and would have already known JH. Pg. 21:

http://www.archive.org/stream/athenaeumcentena00bostiala/athenaeumcentena00bostiala_djvu.txt

Moreover,JH's rocky (legal) relations with John Mein are fairly well documented - JH (and Adams) drew Westminster's attention 1770-1772, if for nothing else, than pure legal matters:

https://www.masshist.org/publications/apde/portia.php?id=LJA01d061

"The issue of a jury's right to decide the law independent of the court's direction or in violation of it (and the closely related question, whether or not counsel could argue law to the jury) claimed much attention in 18th century England and America. It was present not only in this [Mein's] case, but also in Cotton v. Nye, No. 3, and in Rex v. Richardson No. 59."

Please be exact in your comments, Mark. My earlier statement expressed doubt about John Adams’s later claim that Hancock was known “all over Europe” as "King Hancock" in early 1775.

Not just to British officials with responsibility over North America. Not just to London merchants who did business in North America. Of course those people were aware of Hancock as one of Boston’s richest merchants and a leading local politician.

But "all over Europe”? That’s what Adams said, and there’s just no good evidence for that.

In considering Hancock's role in the Mein case, we have to beware of the pitfall of sample bias. The records of that legal action are easily available now because John Adams was involved, so they've been published as part of Adams's papers. If Adams hadn't become President and his family hadn't done such a good job saving his papers, the documents of that case would be filed away with thousands of other debt cases in colonial Massachusetts courts. Did British officials pay much attention to that case? Mein certainly reported on it to them, but they hardly took up his cause.

We must be exact in reading that paragraph from the Adams Legal Papers. It says rightly that the question of jury nullification was a big issue in eighteenth-century British law. It doesn't say that the Mein case was a major example in that argument, or even that anybody writing on the issue brought it up. In contrast, Rex v. Richardson was a major controversy: the Privy Council discussed it in granting Richardson a pardon, and I think the Declaration of Independence refers to it.

Good stuff. Have you heard much about Mein's anti-American writings from London in 1774-75? I just recently read something about them, but there wasn't much context. I see Mein resurfaced briefly in a few New England newspapers in fall 1774, but his name seemed to be mostly forgotten by 1771.

I defer to your expertise. I'm sure I'm missing a large amount of context. But my comment was never about the King Hancock angle. It was instead a reference to your singular sentence:

"Most likely, however, few Europeans had ever heard of John Hancock before the Declaration of Independence."

Am I parsing this too finely ? Perhaps. Probably. But on its face, the sentence is patently untrue, as even an unresourceful hack like myself was able to find some evidence that he was known. If he was extremely well-known in England (and he was), its not a big stretch to assume that others on the continent would have heard of him as well. And that's all I was alluding to. I'd love to spend some time in continental European archives to see what one could dig up. I've never had that luxury myself.

I'd love to hear the talk on Boston newspapers....I wish you the very best on that front. I'm sure its going to be very interesting.

It's not patently untrue, Mark. It's a matter of accepting that there were millions of people in Europe in 1775 and only a small fraction, almost all in the British Isles and almost all directly connected with business in North America, had ever heard of John Hancock. If you can find evidence to the contrary, please share it.

Indeed, please share evidence for your statement that John Hancock was “extremely well-known in England," and "extremely" must mean beyond the metropolitan elite.

I've come across mentions of Mein's writing about America after he left. Harvard holds a document in which he provided the names of various Boston Whigs he'd lampooned. And he claimed that Hancock had tried to have sex with a maid during a trip to London and been unable to perform. The best study of Mein seems still to be John R. Alden's "John Mein: Scourge of Patriots" from 1942, and perhaps there's more to say.

Its convenient for you to employ such parameters in this discussion......you know as well as I do that the avg. person of the 18th c. never had a real voice, and that his sentiments/opinions never made it into the pages of period newspapers or the halls of power for consideration. They were the unrecorded. Nevermind that most people at the time couldn't read. When JH felt he was given the cold shoulder during his London visit, I'm sure he wasn't referring to the locals.

JH was well known where it mattered....in commercial, legal and political spheres, all before the Decl\n of Independence.

Here's a couple things to consider:

A letter sent specifically to John Hancock (JH) in 1766, signed by 50 + merchants in London who dealt with North American trade. They were notifying (congratulating ?)JH of the Stamp Act being repealed, esp. since they considered JH the leading merchant in N. America. It would suggest they saw him as a symbolic leader, as much as a commercial one:

http://myloc.gov/Exhibitions/creatingtheus/DeclarationofIndependence/RevolutionoftheMind/ExhibitObjects/RepealofStampAct.aspx

And JH's own London agents also informing him:

http://archive.org/stream/lettertojohnhanc00harr/39999063782617#page/n0/mode/2up

Over 100 of bills of lading signed by JH between 1761-1774 - a number of which deal with the Board of Ordinance in London.

http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/books-manuscripts/hancock-john-signer-bound-volume-5156243-details.aspx

Letter signed by both JH and John Easson (from the London Board of Ordinance) - Annapolis Royal, NS, 1764. (might have to click link for pg 99).

http://books.google.ca/books?id=vnBEnLRDJoIC&pg=PA99&lpg=PA99&dq=auction+%2B+letter+%2B+john+hancock+%2B+annapolis&source=bl&ots=myptpEozMp&sig=7L2KrMOv_dQ0s1_rTAmJHzZkMAY&hl=en&sa=X&ei=9mWTUeGxGMayqAGn74GIDA&sqi=2&ved=0CCsQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=auction%20%20%20letter%20%20%20john%20hancock%20%20%20annapolis&f=false

Here's a political connection, one of many I'm sure: William Smith, an agent for Apthorpe & Hancock in Halifax was busted for refusing Indian tea, and reprimanded by Francis Legge, the Governor of NS. Francis Legge was a relative to William Legge (Lord Dartmouth), a well-connected statesman in England, and leader of the London Board of Trade in the 1760's. In fact, it was William Legge who appointed Francis Legge as the Governor....

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/legge_francis_4E.html

Stuff like this is obviously the tip of the iceberg.

I'm not the one defining parameters conveniently, Mark. When I wrote "people," I meant people, not one slice of society. When I wrote "Europeans," I meant people from the whole continent of Europe, not just one corner.

You've decided to treat the mercantile elite of British ports as all that matters. To borrow a phrase, it's patently untrue to equate that group with Europeans as a whole. And it's rude to claim that your redefinition of terms allows you to criticize my statement as false.

I still await evidence that John Hancock was known to many people in Europe before 1776, or that he was "extremely well known" in Britain beyond some members of the elite. Just because you can do a Google search and find Hancock's name on trade documents from the 1760s doesn't show either of those things. Have you compared the frequency of his name in contemporaneous sources to those of other big American merchants? Have you considered how many people ever saw bills of lading sent with shipments to London? (Answer: Very few.)

The Hancock in the Apthorp and Hancock firm was John's uncle Thomas.

Post a Comment