The town did not stay calm, as the Newport Mercury reported:

Next Morning the Stamp Master’s Resignation being publickly read, the People announced their Joy by repeated Huzza’s, &c. and the Storm ceased.The whole situation had gone topsy-turvy twice. First, the “Gentlemen” merchants who had led the town’s anti-Stamp protest turned against the self-proclaimed leader of the mob that followed. They put that young man on board the same Royal Navy ship as Martin Howard and Dr. Thomas Moffatt, two targets of that protest. That left him in danger of impressment, so the Newport crowd turned against those local merchants until they brought him back to town.

Things, however, did not continue long in this easy State: An Irish young Fellow, who had been but a few Days in the Town, stood forth, like Massaniello, openly declared that he was at the Head of the Mob the preceding Night, and triumphed in the Mischief that was done. Some Gentlemen, to prevent any further Evil, thought it best to seize immediately upon this Desperadoe, and put him on board the Man of War, which they accordingly did: But this, instead of answering the desired Purpose, kindled a new Fire.

The Mob began again to collect; and a Number of Persons, who, it seemed, were not before concerned, were so irritated as his being carried on board the Man of War, that it became necessary to bring him on Shore again. This was done; and upon his promising immediately to quit the Government [i.e., leave the colony], he was released, and the Night passed without any Tumult.

The Morning following [30 August], Massaniello appeared again in the public Streets, boldly declaring himself to have been the Ringleader of the Mob, and threatning Destruction to the Town, more particularly to the Persons and Houses of those who seized him the preceeding Day, unless they made him Presents agreeable to his Demands.

The Attorney-General, who was the late Stamp-Master, being met and insulted by him, heroically seized upon him; and some Gentlemen running to his Assistance, they carried him off to Goal. This proved effectual;—nobody appeared to rescue him, nor to say a Word in his Favour. He is now under Confinement;—the Town is again in Peace, and we sincerely wish it my continue so.

But then the young man kept threatening disorder, enough to be arrested by the colony’s Attorney General—none other than the central target of that anti-Stamp protest three days before. Johnston had resigned as stamp master and was now helping to stifle class conflict, so the local gentry accepted him again. (As I noted yesterday, the populace was also more lenient on Johnston than on Howard and Moffatt, so he might have had more social capital built up overall.)

One thing that didn’t change was how the other two Newport protest targets were still unwelcome. The 2 September Mercury concluded: “The Ship Friendship, Capt. Lindsey, sailed for England Yesterday. Doctor Thomas Moffat, and Martin Howard, jun, Esq; of this Town, went Passengers.”

The same issue of the Newport Mercury contained this advertisement.

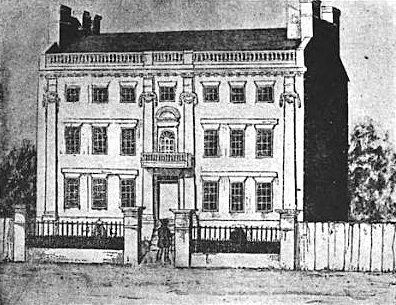

Howard’s house is now the Newport Historical Society’s Revolution House. In London the Crown government gave both supporters new patronage positions, Howard as Chief Justice in North Carolina and Moffatt as a Customs official in New London, Connecticut.

COMING UP: Who was that “Irish young Fellow”?