In May, the Boston Globe ran a story about Boston’s earthquake risk, with a map showing the areas that face the greatest danger. The color thumbnail image in this post shows a detail from that map with the contrasts turned up: the pink parts of the land are more vulnerable to quakes, the cream parts more stable.

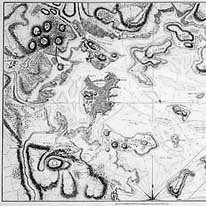

In May, the Boston Globe ran a story about Boston’s earthquake risk, with a map showing the areas that face the greatest danger. The color thumbnail image in this post shows a detail from that map with the contrasts turned up: the pink parts of the land are more vulnerable to quakes, the cream parts more stable.The Globe’s map of relatively safe areas makes a rather close match to a map of Boston and its neighbors in 1775. The grayscale thumbnail image is a detail from one such map, now for sale at Historic Urban Plans.

The Boston of the Revolution (at center, and marked "Downtown" in the new map) is relatively safe from quake danger, along with Dorchester Heights, central Charlestown, and several harbor islands and former islands—i.e., all the dry ground of the 1700s. But much of today’s city was built on landfill in the 1800s: the Back Bay, what we now call the South End, Logan Airport, and land connecting some islands to the mainland. (Modern Boston also includes several parts that were separate towns in the 1700s: Dorchester, Charlestown, Roxbury, &c.)

Most of the areas that glow pink on the modern quake-danger map were underwater at high tide back in 1775. Only one narrow strip of land then connected Boston to the mainland. That's why the settlers of 1630 chose the area as their base, and why the British army could hold off a much larger provincial force for eleven months in 1775-76—a peninsula is easy to defend. Now Boston's old “Neck” has thickened like a wrestler’s so we can easily commute into the expanded city. But one day the original confines of the town may still offer the best refuge.

What an eerie, and non-coincidental, matchup. Your statement that "one day the original confines of the town may still offer the best refuge" reminds me of maps of New Orleans -- contemporary and historic -- after the catastrophe of 2005.

ReplyDelete