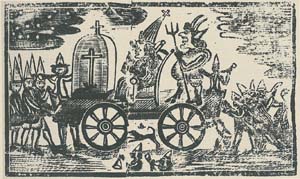

This woodcut shows a Boston Pope Night wagon surrounded by excited boys in conical hats, blowing on horns. On the wagon itself is a "lantern" (like a tent made of oiled paper, illuminated from inside), the effigy of the Pope seated on his throne, and the effigy of the Devil standing on cloven hoofs behind him. Below the wagon runs a little dog, an eighteenth-century cartoonist's way of symbolizing that things had "gone to the dogs."

This woodcut shows a Boston Pope Night wagon surrounded by excited boys in conical hats, blowing on horns. On the wagon itself is a "lantern" (like a tent made of oiled paper, illuminated from inside), the effigy of the Pope seated on his throne, and the effigy of the Devil standing on cloven hoofs behind him. Below the wagon runs a little dog, an eighteenth-century cartoonist's way of symbolizing that things had "gone to the dogs."This woodcut appears on two broadsides that survive from the 1760s, and was probably used on more. The earlier of the two, from 1764 or before, is headlined:

Extraordinary VERSES on POPE-NIGHT.

Or, A Commemoration of the Fifth of November, giving a History of the Attempt, made by the Papishes, to blow up KING and PARLIAMENT, A.D. 1588. Together with some Account of the POPE himself, and his Wife JOAN; with several other Things worthy of Notice, too tedious to mention.

Then comes a long verse about how awful and silly the Pope is; Conrad Bladey has transcribed the text (though laid out in a way that's tough to read) on his Fawkes Day in the USA page. At the bottom of the broadside is the note "Sold by the Printers Boys in Boston"—probably meaning the apprentices had written and printed it themselves.Or, A Commemoration of the Fifth of November, giving a History of the Attempt, made by the Papishes, to blow up KING and PARLIAMENT, A.D. 1588. Together with some Account of the POPE himself, and his Wife JOAN; with several other Things worthy of Notice, too tedious to mention.

One question that should immediately occur to students of history is what exactly those printers' boys thought they were commemorating. The Guy Fawkes plot to blow up Parliament occurred in 1605. "A.D. 1588" was the year of the Spanish Armada. [Incidentally, if you haven't read Garrett Mattingly's The Armada, you really should.]

Furthermore, the broadside never mentions Guy Fawkes or any of his fellow plotters by name. Instead, it first includes the Stuart Pretender among the conspirators, even though in 1605 the Stuarts were still on the British throne (which requires some backing and filling by the "blund'ring Poet"). There's a long digression about the legend of "Pope Joan." The verse doesn't mention attempts by the current Pretender or Charles ("Bonnie Prince Charlie") Stuart to regain the crown, as in 1745, but it does name "Old Harry in his Rome"—Henry Stuart, Duke of York and cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.

In sum, when those printers' devils celebrated Pope Night, they had no clear picture of Guy Fawkes and his barrels of gunpowder under Parliament. They lumped together that Catholic plot against the British government with every other reason they'd heard to hate the Pope, from the attempted Spanish invasion to the number "Six Hundred Sixty six." Then they threw on every insult they could assemble, saying, for example, that the Pope was both married and cuckolded.

I wonder if New Englanders felt some ambivalence about celebrating James I's escape from the Guy Fawkes plot of 1605. A generation later, the Puritans who had founded the Bay Colony helped remove James's son Charles I from the throne. New Englanders sheltered three "regicides"—members of the Cromwellian Parliament who voted to execute that king; one was buried in the town of Stow. So it might have been easier for Bostonians to treat the Fifth of November as an all-purpose anti-Catholic holiday than to celebrate the deliverance of a Stuart king. That may explain why in New England the Fifth of November wasn't Guy Fawkes Day, but Pope Night.

Both broadsides about Boston's Pope Night illustrated with the woodcut above are reproduced in the Dublin Seminar volume New England Celebrates.

TOMORROW: Pope Night Gets Political in the 1760s—or does it?

No comments:

Post a Comment