It came from the young merchant and future Loyalist Isaac Winslow (1743-1793), who wrote:

The 5th of November happily disappointed ones fears, a union was formed between the South and North, by the mediation of the principal gentlemen of the townThat year’s Pope Night was unusual. In 1764 a morning tussle between North End and South End gangs with their big wagons had accidentally killed a young boy. Town officials tried to confiscate the wagons and effigies, but the gangs brought them out again at the end of the day and proceeded to their usual brawl. That evidently left one of the gang leaders seriously hurt (a detail I hadn’t read before).

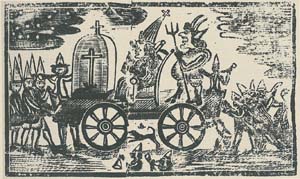

[The Pope effigies] paraded the Streets together, all day, and after burning them at the close of it, all was quiet in the evening. There were no disguises of visages, but the two leaders, [Ebenezer] M’cIntosh of the South, and [Henry] Swift of the North, (the same who was so badly wounded last year[)], were dress’d out in a very gay manner

Furthermore, in the late summer of 1765 Boston had been roiled by protests against the Stamp Act, culminating in a riot that nearly destroyed Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s North End mansion. The town’s political leaders were determined not to let the Fifth of November revelry get out of hand. That would have damaged not only local property but Boston’s reputation elsewhere.

Whig gentlemen bribed and cajoled the gangs into acting peacefully. By promising the young men a banquet, they made collecting money through the traditional processions unnecessary. Then the men called on the youths to channel their energy into a dignified patriotic parade against the Stamp Act rather than a battle against each other. That worked for 1765, and the next few Pope Nights in Boston were relatively peaceful as well.

The quotation above comes from a family history called the “Winslow Family Memorial”; researchers can download Robert Newsom’s transcription of it in PDF form from the M.H.S. website.

No comments:

Post a Comment