As I quoted back here, the father of that family was Bartholomew Green, trained by his own father as a printer but making his living spotting ships as they came into Boston harbor. The source of that information, Isaiah Thomas, also reported, “he had some office in the custom house.”

The Customs service rented a house on King Street near the Town House from the widow Grizzell Apthorp. The Green family lived in the building, apparently supplying housekeeping and meals for the Customs staff working there. Green might also have been a tide-waiter or some other low-level employee during the day; Treasury Department records could preserve more detail.

When four British army regiments arrived in town in the fall of 1768, Boston’s Whigs began to send a series of reports about how horrible they were to newspapers in other American ports. Oliver M. Dickerson collected these heavily slanted dispatches in a 1936 book titled Boston Under Military Rule. One item dated 26 Jan 1769 described a concert the night before that British army officers had attended:

Some officers of the army were for a little dancing after the music, and being told that G[overno]r B[ernar]d did not approve of their proposal, they were for sending him home to eat his bread and cheese, and otherwise treated him as if he had been a mimick G[overno]r; they then called out to the band to play the Yankee Doodle tune, or the Wild Irishman, and not being gratified they grew noisy and clamorous; the candles were then extinguished, which, instead of checking, completed the confusion; to the no small terror of those of the weaker sex, who made part of the company.—Thus, as of January 1769 the Boston Whigs considered Green “inoffensive,” despite his work for the hated Customs Commissioners. Or at least they were ready to portray him that way if it made rowdy army officers look bad.

The old honest music master, Mr. [Stephen] D[e]bl[oi]s, was roughly handled by one of those sons of Mars; he was actually in danger of being throatled, but timously rescued by one who soon threw the officer on lower ground than he at first stood upon; the inoffensive Bartholomew Gr—n, who keeps the house for the Commissioners, presuming to hint a disapprobation of such proceedings, was, by an officer, with a drawn sword, dragged about the floor, by the hair of his head, and his honest Abigail, who in a fright, made her appearance without an head dress, was very lucky in escaping her poor husband’s fate.

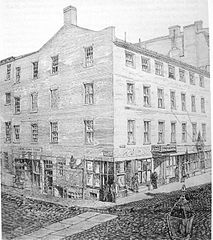

[The picture above is said to show Concert-Hall as it appeared in the mid-1800s; it might have been expanded since 1769.]

"made her appearance without an head dress,"! Oh dear. Well, we'll forgive her this once.

ReplyDeleteA clear sign of panic in the "weaker sex."

ReplyDeleteWhat is your source of information about Grizzell Apthorp renting the town house to His Majesty's Customs? There's an article in the Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series, Vol. 46 (Oct.,1912 - Jun., 1913), pp. 468, that notes the Joseph Harrison opened the first custom house in Boston after he was appointed customs collector on October 28, 1766. I wonder whether the fact that Boston had a real brick and mortar custom house helped Charles Paxton advocate for Boston as the seat of the American Board of Customs Commissioners while Paxton was in London in 1766-67. See, The American Historical Review, Vol. 45, No. 4 (Jul., 1940), pp. 778.

ReplyDeleteHiller Zobel, citing a Treasury Department document, says Grizzell Apthorp was the Customs Commissioners’ landlady on page 66 of The Boston Massacre.

ReplyDeleteIn addition, James Murray wrote of “the Custom house (Apthorp’s house)” in a letter on 12 Mar 1770, printed in Letters of James Murray, Loyalist.

In addition, Boston real estate records show that that corner of King (State) and Exchange Streets belonged to the Apthorp family for three generations, from Charles to his granddaughter Sarah Morton.

ReplyDeleteGreat. Thanks for the sources.

ReplyDelete