The conversation is as much about the process of writing that book and the current public debate about Revolutionary legacies as about the American Revolution itself.

That approach has its own interests, as this long passage from Holton early in the conversation shows:

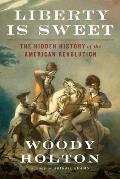

I really wanted to reach people who love history but don’t realize that what they have seen so far—mostly wealthy white men—is only the tip of the iceberg. My pitch to American Revolution lovers is that their favorite topic becomes even more exciting when you fully engage with its ambiguity and kaleidoscopic diversity.Here’s the whole interview.

My focus on non-scholars shaped the book in two ways, only the first of which I anticipated. I knew history buffs would want a narrative, and I was happy to provide one, since one of my main points is that women’s, Indigenous, military, and all the other histories transpired on the same timeline, constantly influencing each other, and we miss a lot when we devote one chapter to African Americans, one to diplomacy, one to the economy, and so on. But going chronological does not have to mean merely telling stories. I tried to use events like the boughs of a Christmas tree, with the ornaments being placed where I paused the narrative to share various social historians’ insights as well as my own.

The unintended consequence of my determination to reach beyond college towns was that I became a military historian! My initial attitude toward the battles was cynical: amateur historians demand them, so I had to write them up. But as I began that research, I overcame the conventional academic prejudice that military history is mere storytelling, and I ended up offering what I consider some fairly new interpretations of the war.

Here’s one: the British realized early on that they could not win, since whenever they captured a hill—starting with Breed’s/Bunker—at the cost of 50 percent casualties, all the rebels had to do was drop back to the next hill and start the process over again. So all the Whigs (I found Patriots too partisan) had to do was stay on defense. But George Washington was initially bent on going on offense, and his classic elite-British-empire-masculine aggressiveness several times nearly ended in disaster. But he learned from his mistakes, and while he devised nearly a dozen plans to drive the British from their headquarters in Manhattan, he never actually executed even one of them. Ultimately Washington’s greatest contribution to the war effort was restraining his own aggressive instincts.

No comments:

Post a Comment