Monday last being the Anniversary of the Commemoration of the Preservation of the British Nation from the Popish Plot, the Guns at Castle William and at the Batteries in Town were fired at One o’Clock.This article was probably written to put Boston in the best possible light for readers, both locally and in other towns. It may therefore not be correct in all its implications.

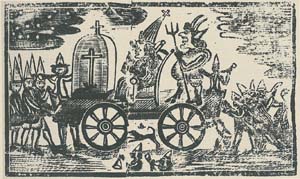

It was formerly a Custom on these Annniversaries for the lower Class of the People to celebrate the Evening in a Manner peculiar to themselves, by having carved Images erected on Stages, representing the Pope, his Attendant &c. and there were generally carried thro’ the Streets by Negroes and other Servants, that the Minds of the Vulgar might be impress’d with a sense of their Deliverance from Popery, and Money was generally given to regale themselves in the Evening when they burnt the Images.——

But of late those that are concerned in this Pageantry make a Party-Affair thereof, and instead of celebrating the Evening agreeably, the Champions at both Ends of the Town prepare to engage each other in Battle, under the Denomination of South End & North End.— . . .

It should be noted that these Parties do no subsist much as any other Time.

First, the custom of moving around effigies of the Pope, Devil, and others wasn’t peculiar to Boston. Most New England ports and many British towns observed Pope Night the same way (though they might have different names for the holidays). There were giant effigies, often on wagons; appeals for money; and a bonfire after dark.

The dismissal of the celebrants as “the lower Class of the People,” “Negroes and other Servants” (probably meaning apprentices), and “the Vulgar” disguised how broadly the population participated in Pope Night. Even if genteel men didn’t join the crowds, their treats funded the activity. Women and girls watched and might have helped the preparations.

Perhaps the biggest question is whether the North End–South End divide really did disappear on most other occasions, as the newspaper claimed. We know that there were separate North End and South End Caucuses in town politics in the early 1770s, though they tried to work together. According to Henry Adams, a version of that rivalry (turned into a fight between the Boston Latin School students and every other boy) persisted until the mid-1800s.

In one important respect, the New-Letter report seems accurate: only in Boston did the Pope Night celebrants divide into neighborhood gangs and end the night with a head-bashing rumble. Joshua Coffin’s detailed 1835 account of the event in Newburyport, for instance, mentioned nothing of the sort. That town’s young men and boys all worked together.

The News-Letter implied that this neighborhood brawling was a recent development, added on top of the genral rowdiness of procession and pageantry. But how recent? The intra-town fight was reported in a newspaper as early as 1745, or before at least some of the brawlers of 1764 were born.

The 1764 celebration was actually fatal—but was that the fault of the gangs?

TOMORROW: The first death.

No comments:

Post a Comment