Author Gene Procknow has shared his thorough early review:

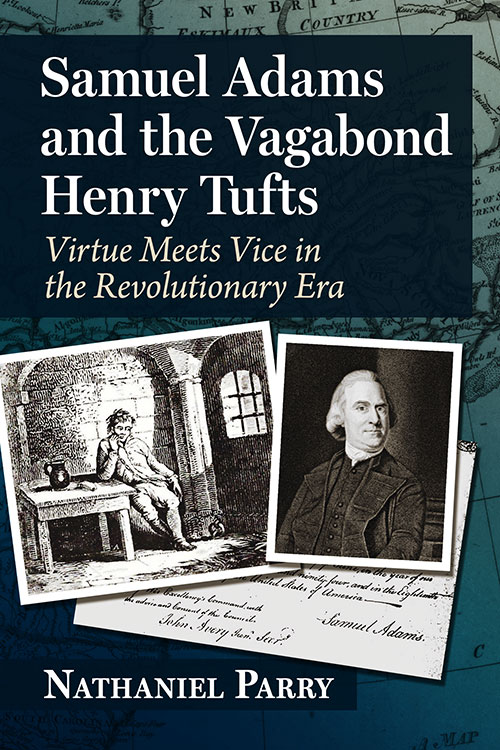

Comparative founder profiles are a crowded book genre with numerous volumes depicting any combination of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin as rivals, friends, or brothers. Nathaniel Parry offers a novel twist to this well-trod approach by comparing the lives of a famous founder, Samuel Adams, with a common criminal, Henry Tufts. . . .While most of those dual biographies could trace a long relationship between their subjects, in this book the insights arise from the big gap between the two men.

Their lives briefly intersected in 1794 when Massachusetts Governor Adams saved Tufts’ life by commuting the thief’s death sentence to life in prison.

While Adams was devoted to political action, for example, Tufts joined the Continental Army only for the enlistment bonus and then promptly deserted. He was a habitual criminal, though Parry “asserts that if he were a tea smuggler rather than a thief, Tufts would be lauded as a Revolutionary hero.” Tufts did get a certain amount of glory as a rogue from his 1807 autobiography, most likely ghostwritten, which is the main source on his life.

The similarities between the two men can also be telling in reflecting attitudes that permeated their society. Procknow highlights how they shared common sentiments about slavery and race. Even after spending years with the Abenaki, Tufts (or at least his book) refers to Native Americans as “savages,” a term Adams also used.

At times, the review says, Parry pushes too hard on its theme of socioeconomic difference:

For example, the author overplays class conflict by asserting that Continental Army officers were “motivated more by class advancement than by deeply held convictions for the revolution” and, as evidence, cites a lieutenant who fought at Bunker Hill and Benedict Arnold’s self-aggrandizement (142, 241). However, for the vast majority in the Continental Army, officer advancement did not lead to newly found post-war wealth or status. . . .In all, Procknow concludes, by “innovatively comparing the lives of Samuel Adams and Henry Tufts,” Parry does a good job showing how “the nation’s founding was the product of elites and ordinary people” both.

Other minor weaknesses include several technical misstatements such as mislabeling Congressional members (Roger Sherman represented Connecticut, not Massachusetts), the object of British troops on the Lexington and Concord raid (General Thomas Gage sought four missing cannons and not the capture of Samuel Adams and John Hancock) and the number of allowable lashes in the Continental Army (100 was the maximum, not 500).

No comments:

Post a Comment