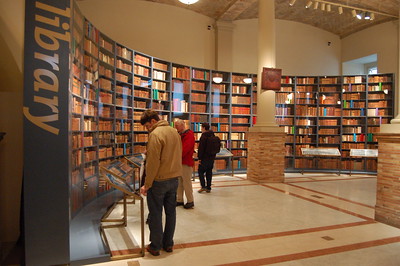

The B.P.L. had a handsome exhibit of those books in 2006-07, as shown here courtesy of Brian O’Connor. More recently it digitized the collection through the Internet Archive.

Scholars have long studied those volumes, many of which include Adams’s notes responding to what he read. Now everyone can look at images of those pages and see how, for instance, he engaged in a running debate with Mary Wollstonecraft on the French Revolution.

John Adams and his family also left a very large archive of manuscripts—letters, diaries, trial notes, drafts of essays, expense accounts, and so on. In 1956 the Adams Manuscript Trust donated all those papers to the Massachusetts Historical Society. Since then the M.H.S. has managed an extensive program to transcribe and publish the family documents, both for scholars and the public.

The text of the published papers appears online within the M.H.S. website and at Founders Online. Images of the correspondence of John and Abigail Adams, John Adams’s autobiography and diary, and John Quincy Adams’s diaries, among other documents, can also be viewed online.

The Adams family also deeded their historic houses in Quincy to the National Park Service, starting in 1946. The Adams National Historic Park complex now includes a stone building erected in 1870 for John Quincy Adams’s library, significantly larger than his father’s (though he inherited about 10% of those books).

In 1939, Franklin D. Roosevelt forged a new path for handling his Presidential and other papers. He established a library on his estate at Hyde Park, New York; raised money to fund it; and turned it over to the U.S. government through the National Archives. That became a model for a new institution: the Presidential library. Soon Harry S Truman and Herbert Hoover followed that example. After the Watergate crimes, the U.S. Congress mandated that Presidents’ official papers remained part of the National Archives, no longer their personal property.

Presidential libraries have become so popular that private and public institutions have been establishing libraries for earlier Presidents. Some of those places are the repositories of the President’s papers, but others aren’t.

For instance, the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon doesn’t own Washington’s papers; those are, for the most part, at the Library of Congress and the Library of Virginia. It doesn’t own Washington’s own books; the bulk of that collection is at the Boston Athenaeum. But the library at Mount Vernon has quickly established itself as a study center with a large collection of published studies, fellowships, and public programs.

The Presidential libraries also often function as shrines to their subjects, on par with their birthplaces and mansions. Those libraries are tourist sites as much or more than anything else. There’s ongoing tension between showing each President at his best and promoting objective, scholarly assessments of his actions and legacy.

All that brings me to this year’s twist in the story of the John Adams Library. In January Thomas Koch began his sixth term as the mayor of Quincy. In his inaugural address he outlined several ambitious plans for city institutions. Among them, according to the Quincy Patriot-Ledger:

Koch said he will work to bring the John Adams Book Collection back to the city and create a John Adams Presidential Library in the Adams Academy Building. The book collection was loaned to the Boston Public Library decades ago, Koch said, because the city didn’t have the facilities to care for or display them.Now that’s not what Adams Temple and School Fund said in 1893 when it decided to move the Adams collection to the Boston Public Library. The books were then in Quincy’s recently built Thomas Crane Public Library, and there doesn’t seem to have been any suggestion they weren’t safe. Rather, the alleged problem was that nobody was coming to Quincy to study them.

“I am proud to say that thanks to the passion and hard work of a lot of people, those reasons no longer apply. That’s why I plan to petition the Boston Public Library and the City of Boston to return the books to their rightful home in Quincy,” he said.

TOMORROW: How would this proposal for a John Adams Presidential Library work?

No comments:

Post a Comment