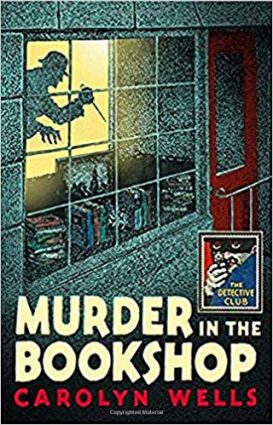

In Murder in the Bookshop (1936), Wells’s MacGuffin is a small book signed by Button Gwinnett, delegate to the Second Continental Congress from Georgia.

Gwinnett was one of the fifty-six men who signed the Declaration of Independence. He died less than a year later, on 19 May 1777, leaving behind a much sparser paper trail than his colleagues who didn’t engage in dueling.

In the nineteenth century, there was a craze for collecting historical autographs, which resulted in the mutilation of lots of letters and forms. Wealthy Americans competed to own a signature from each Declaration signer. Gwinnett was the rarest. As of 2016, only fifty-one examples of his signature were known to survive, with only ten of those in private hands.

It would thus make sense for a book signed by Gwinnett to be worth a lot of money, possibly even worth killing for. A character in Murder in the Bookshop describes the object of desire this way:

“It’s a small book, a pamphlet, but in fine condition. It is entitled Taxation Laws of Great Britain and U.S.A. Gwinnett was a student of Government and Politics and this was his book. He had not only autographed it on the fly-leaf but had signed it two other times and, moreover, had made annotations in his own hand on various pages. So you can grasp the importance of the book. Such finds do occur, but very seldom.”My eyes perked up at that description, but not because I imagined the book as valuable. I knew that there were no ‘taxation laws of the U.S. of A.’ by the time Gwinnett died in 1777 or for many years afterward. The U.S. government didn’t become a legal entity until the adoption of the Articles of Confederation in 1781, and didn’t gain the power to levy taxes until after the new Constitution in 1789.

Thus, there couldn’t have been a copy of Taxation Laws of Great Britain and U.S.A. printed in time for Gwinnett to sign it. Was that a clue? Perhaps the detective would reveal this book was a fraud, and the finger of suspicion would swing toward the book dealer.

But as I read a little further, it became clear that all the characters in Murder in the Bookshop behave absurdly. No one comes across as a genuine, logical person.

Wells knew the world of book-collecting well—she amassed a top-notch collection of Walt Whitman material. She wanted to set a story in that milieu. But by this point in her writing career, she was putting out four mysteries a year, and it seems that she expected readers to value the right twists (secret lovers! second murder! kidnapping! masked genius!) more than logic.

No comments:

Post a Comment