Almost no other mentions of maypoles appeared in the colonial American press in the quarter-century leading up to the Revolutionary War. But from that handful of items, this one stood out.

It appeared in the Boston Post-Boy on 17 Sept 1770:

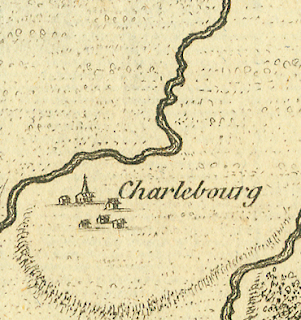

QUEBEC, August 9.Charlebourg was then a village north of Québec; today, spelled Charlesbourg, it’s a borough of the city.

On Monday last there was a dreadful Thunder-Gust at Charlebourg, which lasted for 2 Hours, and first struck a May-Pole, standing before the Parsons House, carried away the Weather-Cock and the Iron Rod, which fell to the Ground without being melted or damag’d, tho’ the May-Pole was very much shatter’d,

it [the lightning] then fell on a House where it tore the Inside of a double Chimney, struck a Woman who was kneeling at the side of the Chimney, who did not survive afterwards longer than to repeat three times, My God, I am dying: Help.

On examining her Body, the Bones of her Arms were found to be broken, without any outward Marks; in the Back Part of her Shift was a Hole the Size and Form of a Canon-Ball, and on her Back a Mark of the same Size and Figure, without any Scratch.

The French settlers in Canada had brought their own maypole tradition to the New World. According to Gilbert Parker and Claude G. Bryan’s Old Quebec (1903), that city’s pole was “surmounted by a triple crown in honour of Jesus, Maria, and Joseph.” Old-fashioned New Englanders would of course have seen all of that paraphernalia as well deserving of a lightning strike.

Québecois erected new maypoles as they moved west. In 1778 the Scotch-Irish fur trader John Askin wrote from Michilimackinac (now Mackinaw City, Michigan), “je ne crois pas que Le may que Monsr. Cadotte a planté Regarde personne de Bord que vous ne vous servés pas pour des pavillions”—I don’t think the maypole Mr. Cadotte planted matters to anyone as long as you don’t use it as a flag-staff.

The famous Quincy family of Massachusetts chose Mount Wollaston as the name for the Quincy estate, which is amusing. The name derived from the original English plantation in the area, established in 1625 by a Captain Wollaston. But the early settlers soon changed the name to Merry Mount, in celebration of their riotous living. A contemporary account described one such scene of “great licentiousness of life”: “they setting up a Maypole, drinking and dancing about it, and frisking about like so many fairies, or furies rather; yea, and worse practices, as if they had anew revived and celebrated the feast of the Romans’ goddess, Flora, or the beastly practices of the mad Bacchanalians.” See Nathaniel Morton, New England’s Memorial (Boston: Congregational Board of Publication, 1855), p. 91.

ReplyDeleteThe Adams family came into possession of Mount Wollaston in the nineteenth century and were well aware of the disputes between Thomas Morton’s settlement and New England’s dominant Puritan communities. John Quincy Adams II (1833–1894) named his home “Merrymount” in recognition of the early settlement there.

ReplyDelete