I’ve studied schooling in Boston, but the opportunities there weren’t typical for a mainly rural society. Shammas offers a wider view:

The eighteenth century addition of cursive handwriting and arithmetic to reading as the desired skills to be transmitted to free boys and then girls in a primary school environment notably increased the cost of education. The latter two skills demanded classrooms, textbooks and stationery supplies. . . . Children had to go to school, often a distance away, and that journey meant taking time from their field or domestic work and employment from a third party that supplemented their family’s income. . . .Shammas holds the John R. Hubbard Chair Emerita in History at the University of Southern California. Having written books about inheritance, household government, investing, consumption, and other aspects of everyday life in America and Britain, she is currently studying “the long, torturous process whereby American children mastered the three Rs.”

Consequently, the poor relief records that I examined indicate that children of indigent parents most commonly obtained schooling through the indenturing of their labor to a master until they reached adulthood, 16-18 for girls and 21 for boys. . . . In exchange, this system required the new master to take over support of the child by providing him or her with shelter, food, and clothing as well as a specified amount of instruction—boys sometimes received instruction up through arithmetic and girls usually learned reading and needlework. Other indentures instead set aside a time period for schooling, never more than one quarter a year (13 weeks), and usually in the winter, which in an urban area could also be in the evening. In effect, these children self-funded their education through their labor services. . . .

Children in rural areas had more difficulty accessing their schoolhouses during bad weather, which kept them home more than students in cities. Additionally, farmers, more than workers in other occupations, viewed what they called “ornamental” learning suspiciously and had greater reluctance to increase the time devoted to their children’s education.

Census data revealed these trends. I found in a one-of-a-kind school census from 1798 for New York state that children living in more newly-settled, low-density, high-fertility agricultural areas attended school for a significantly fewer number of days than did children living in more urban and less agricultural counties. All in all, the average attendance in those counties ranged from 9-13 weeks. . .

Because of the need for child labor, few boys or girls enrolled for a full academic year or the equivalent of three quarters, and even fewer attended even 90% of the time. Because the majority of North American households engaged in agriculture, boys could be utilized for fieldwork and animal husbandry most months. However, having only a quarter year of schooling meant that children had to constantly re-learn material the following year before they could be presented with new lessons.

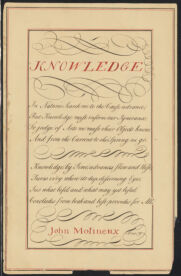

(The image above is a handwriting specimen that John Molineux produced in the 1760s for his writing-school master, Abiah Holbrook, now in the Harvard University library collection.)

No comments:

Post a Comment