I was struck by this

passage from an interview by Jack Miller Center Resident Historian Elliott Drago with J. L. Tomlin, a professor at Fairmont State University:

We read early American source material too often with the arrogance of speaking the same language we are reading in the sources. We presume to know exactly what they meant with the words they used. The prevalence of anti-Catholic language, for instance, was simply chalked up to Protestant fear and hatred of Catholics for decades of scholarship. This explanation, however, doesn’t hold up when we realize they were calling each other Papists or labeling certain behaviors Popish [despite all obviously being Protestants].

The popular culture of the time had taken the word and developed it into an expression of something entirely different. It becomes clear we didn’t understand how these words or phrases were actually being used or their real meaning.

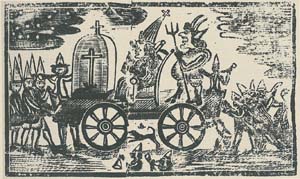

That understanding of “popery” as something infused through Roman Catholicism but not confined to it, Tomlin argues in his dissertation, gave “anti-popery” a wider meaning than just anti-Catholic bias.

…religious slurs came to be a vehicle to articulate aspects of a preferred political economy and governing system. In so doing, it reveals a founding paradox of American history: language born of xenophobia, sectarianism, and fear was used to articulate a political and social vision based in gradually expanding pluralism, tolerance, and political optimism.

Of course, vocabulary that equated Catholicism with authoritarianism reinforced the underlying prejudices against Catholics even as it might prove useful in discussing the overwhelmingly Protestant politics in America at this time.

No comments:

Post a Comment