The Wall Street Journal just ran Prof. William Anthony Hay’s laudatory review, which zeroes in on a fundamental aspect of John Hancock’s character:

As Ms. Barbier emphasizes, Hancock possessed an innate sociability—it was a core aspect of his identity: He wanted to be liked. Not for him the disciplined reserve of his fellow New Englanders, the aloof dignity of George Washington and the Virginia planter class, the intellectual ferocity of John Adams. He was, though hardly ordinary, never a grandee; for all his display, he radiated an affability that would appeal to social orders well below his own. . . .I think that last part of the review shortchanges Hancock’s dominant role in Massachusetts’s state government. He was, after all, governor for eleven of the thirteen years from October 1780 to October 1793, never losing a race. That was also the period when he fully threw himself into being a politician instead of a merchant who dabbled in politics.

Hancock was not “all-in” for independence at first. Far from seeing a march to inevitable confrontation between the colonies and the crown, he hoped that the reversal of certain policies—like the Stamp Act and the Townshend Duties, a range of taxes on goods imported from England—would restore good relations. Tensions would fade, he believed, along with resistance. And tensions did fade for a while.

It was a tax on imported tea—the only duty left over from the hated Townshend program—that pulled Hancock back into an oppositional mode. Trouble peaked on Dec. 16, 1773, with the Boston Tea Party, during which a disguised mob threw cargo into the harbor. Hancock took no direct part in the act but had rallied a crowd at the Old South Meeting House that night by declaring: “Let every man do what is right in his own eyes.” . . .

It is safe to say that, at this point, the “moderate” Hancock was in abeyance, but he was not gone. At the Continental Congress—which began in 1774—Hancock tried to balance the proponents of reconciliation against the radicals, though he did see the necessity of independence once British authorities rebuffed overture after overture. Ill health took him from the forefront of events when he stepped down from the congress in 1777.

Still, Hancock kept his hand in affairs. During the war, he tempered local hostility to France, a Roman Catholic ally that had lately been a bitter foe in Canada. After the war, he checked tensions arising from the discontent of indebted farmers and artisans. He urged Massachusetts to ratify the federal Constitution—but with amendments that would safeguard liberties.

Barbier’s book doesn’t omit Hancock’s activity after the Declaration of Independence, devoting a quarter of the chapters to those years. Being the biggest man in Boston may seem anticlimactic to Wall Street Journal readers, but in a period when state governments wielded more power than the national government, being the popular governor of a big state was a very big deal.

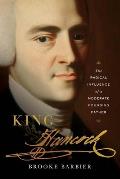

I've been looking forward to this book. There hasn't been a good biography of John Hancock available for quite some time; and he deserves one. I heard Brooke talk about the book at History Camp back in August, and I'm really excited that she's written it.

ReplyDeleteHarvard Book Store in Cambridge is hosting an author night for Brooke on Wednesday, October 25. It seems to be her only local event this fall.

[A completely unpaid announcement.]