Pope Night is turning out very long this year. Some

Boston 1775 readers thought yesterday’s description of the Fifth of November celebration in 1765 put too much emphasis on upper-class gentlemen manipulating the crowds. But I can read the same events the other way as well: the crowds manipulating the elite. Or perhaps both groups got what they wanted together.

There are many more sources from the genteel class than from the working class, of course. Rich men of all political persuasions wrote about the “mob” with distaste. Friends of the royal government blamed

riots on secret Whig instigators. Whigs blamed the same events on oppressive laws spurring entirely foreseeable anger from the lower sort. No one recorded much about what workingmen themselves thought, how they organized, and what they hoped to accomplish.

Alfred F. Young’s “

Ebenezer Mackintosh: Boston’s Captain General of the

Liberty Tree,” an essay published earlier this year in

Revolutionary Founders, collects what we know about the most prominent working-class political figure in pre-Revolutionary Boston.

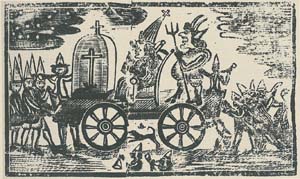

Mackintosh, a twenty-seven-year-old shoemaker, was the captain of the South End gang in 1764. It looks like the youth of that part of Boston chose him for that post, along with some unnamed lieutenants, but we have no idea how. The South Enders won that year’s Pope Night brawl, but a young boy was killed, town officials tried to seize the wagons, and North End captain

Henry Swift lay in a coma for days.

In March 1765 Mackintosh, Swift, and others were indicted for rioting, with a stern lecture from Chief Justice

Thomas Hutchinson. Yet the same month, Bostonians elected Mackintosh as a Sealer of Leather, one of the town’s many inspectors. So clearly he was still popular, and commanded some respect from the men who could vote in

town meeting.

The next month brought news of the

Stamp Act, scheduled to take effect at the start of November. Boston was the site of America’s first public protest against that law, carried out by a large crowd in the South End on 14 Aug 1765. With Ebenezer Mackintosh as a very visible leader, that protest used the same sort of effigies as on Pope Night. The elm hanging over the proceedings was later dubbed “Liberty Tree,” and Mackintosh became its “Captain General,” a term borrowed from the

militia.

Behind the scenes, it looks like the

Loyall Nine, a group of young merchants and luxury craftsmen, did much of the preparation for that protest. Records also show that two days before it

Samuel Adams had sworn out a warrant for unpaid taxes against Mackintosh and his partner; later, Adams apparently dropped that matter. Was that because Mackintosh had kept the violence under control and directed against the property of Stamp Act agent

Andrew Oliver?

On 26 August, a more spontaneous crowd sacked Hutchinson’s house in the North End. That’s a very murky affair, made murkier by Hutchinson’s conspiracy theories. Mackintosh was arrested for the riot, then let go on the grounds that there would be worse trouble if he were locked up. No one preserved evidence that Mackintosh was actually involved, but by then many officials perceived him as controlling the Boston crowd.

That fall, protests against the Stamp Act spread up and down the Atlantic coast. In Massachusetts it became clear that Oliver wouldn’t be able to collect the new tax, and that judges and other officials would proceed without requiring stamped paper. With that struggle going his way, and legal threats still hanging over him, Mackintosh had an incentive to help keep Boston peaceful. At the same time, his South End gang constituency was probably looking forward to their Pope Night celebrations.

Yesterday’s posting said that town leaders convinced the South End and North End gangs to forgo their traditional brawl on 5 Nov 1765 by supplying a festive banquet instead. In fact, gentlemen paid for large quantities of food and drink three times that fall:

- In late October, the two “richest men in town”—perhaps John Hancock and John Rowe—hosted two hundred workingmen at a tavern, with Mackintosh and Swift at the head table.

- On Pope Night, there were refreshments for all under Liberty Tree as the gangs rolled their wagons around peacefully.

- There was another formal dinner a week after the holiday, filling five rooms.

Furthermore, merchants gave the Pope Night officers new blue and red uniforms, hats, and canes. The young men first wore those in a public march on 1 November, the day the Stamp Act was to take effect. Mackintosh walked alongside

William Brattle, general of the Massachusetts militia and

Council member. A gentleman and a shoemaker, South Enders and North Enders, Pope Night officers and militia units—Bostonians thus showed their unified opposition to the Stamps. If Pope Night was all about having fun while showing off one’s patriotism, those parades and banquets accomplished the same thing without anyone getting bashed on the head.

Mackintosh wasn’t just getting a few meals and a fancy coat, furthermore. He was also getting a seat at the political table, a show of respect from gentlemen. There’s some evidence Mackintosh did have a wider political consciousness; he named his first son after a famous Corsican rebel. But we don’t have any sense of his platform, or how he might have differed on issues with the town’s rich merchants and employers. Was he a puppet, or a puppeteer, or just another actor in a complex process?

Supporters of the royal government and officials in London continued to worry about Mackintosh until the start of the war. Back in Boston, he was never prominent after 1766. Debt, the death of his wife, and possibly drink caught up with him. Mackintosh took his children to Haverhill,

New Hampshire, in 1774.

More genteel men such as

Dr. Thomas Young and merchant

William Molineux became the Whigs’ street leaders. Members of the Loyall Nine, such as

Thomas Crafts, rose to more high political offices. As for the crowds, they continued to act on their own, sometimes supporting Whig positions and sometimes defying pleas from Whig leaders. Even Mackintosh couldn’t really control everyone.