So here’s what the Whigs reported on 27 Dec 1768:

A report is current, that Mr. Alderman T—k, has procured a copy of the will or instruments whereby C—m—r P——, gave to the late C. T——d, the reversion of an estate represented to him as worth £50,000—which he intends to produce in the House of C—m—s next s—s—n, in order to shew what secret influence had been exerted for the procurement of an American B—d of C—s—ms.Well!

It might also be of special service to present that H—e with the picture of a certain lady of pleasure, whose influence was powerful enough to procure £500 a year for a B. that those guardians of the people might see how the monies taken from Americans is charmed away and applied not for the lessening of the national debt but for the support of M——l w—h—s and p—si—s.

Let’s translate.

- “Mr. Alderman T—k” was Barlow Trecothick, a leader of the London merchants who did business with the North American colonies. He had trained with and married a daughter of the late Boston potentate Charles Apthorp. Massachusetts merchants considered him one of their best friends in Parliament. They didn’t know that on 15 November Trecothick told the House of Commons, “I look upon America as deluded.”

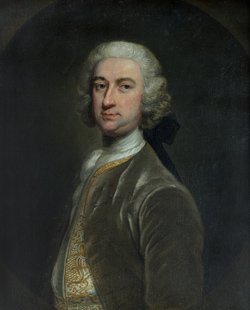

- “C—m—r P——” was Charles Paxton, one of the Commissioners of Customs in Boston (shown here). He was the most unpopular of those five men at this time, having worked at the port’s Customs house for years before getting the big promotion of overseeing the service across North America.

- “the late C. T——d” was Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer in London until his unexpected death in September 1767. He designed the Townshend Acts, which imposed duties on certain goods shipped from Britain to North America in order to pay for colonial administrators’ salaries.

- “in the House of C—m—s next s—s—n”: in the House of Commons next session.

- “American B—d of C—s—ms”: American Board of Customs.

It’s true that Paxton was in London while Townshend wrote the new law. However, the sparse surviving correspondence between the two men shows no friendship or close collaboration. Townshend was already talking about reforming American colonial government before Paxton arrived.

Trecothick never produced the rumored evidence of corruption. Indeed, he may have had no idea about how the Boston Whigs were invoking his name in spreading this conspiracy theory.

In the second sentence above:

- “that H—e”: the House of Commons.

- “a certain lady of pleasure”: no idea.

- “£500 a year for a B.”: a Board? a Baronet? (Gov. Francis Bernard was made a baronet in 1769, and his pension indeed turned out to be £500.)

- “M——l w—h—s and p—si—s”: ministerial whores and pensioners.

Underneath that accusatory propaganda was a serious political issue. The Townshend duties were enacted by a Parliament where the colonists had no representatives, and they were earmarked in part to insulate royal appointees from colonial pressure through regular salaries. Charles Townshend really did seek to increase London’s power in the colonies, and Charles Paxton really was one of the bureaucrats charged with and benefiting from that effort.

No comments:

Post a Comment