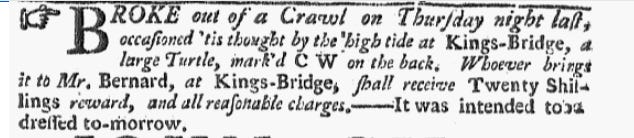

Here are some tasty extracts from Washington biographer Alexis Coe’s conversation with Prof. Mary Draper about the background behind this ad:

Mary: In the 18th century, colonists throughout British America loved eating turtle. No one compared it to chicken (that I know of), but people routinely likened it to venison or veal. Merchants would ship live turtles in the hulls of vessels — alongside the other goods they bought and sold in the Atlantic world. They kept them alive by dousing them with salt water every few days.More details and pictures at Coe’s website.

When these vessels cruised into port, their arrival was cause for celebration. Merchants took out ads in local newspapers. Tavern keepers announced turtle feasts. And members of the early American elite attended “turtles” — elaborate parties where guests dined on turtle meat and caroused late into the evening. . . .

Alexis: The turtle escaped the day before it was to be cooked and eaten! What drama! But why is “CW” on the turtle’s shell? I hope it was painted, but I’m guessing it was carved.

Mary: Sometimes, these turtles were destined to specific people from the moment they were loaded onto a vessel. A local merchant might solicit a ship captain, asking him to acquire a turtle. Or someone living in a more tropical location might ship a turtle to friends elsewhere in the Atlantic world. When this happened, the turtle was marked with the recipient’s initials. I’ve come across other ads and letters that mention these markings and, sadly, they seem to be carved.

In 1776, The Pennsylvania Evening Post chronicled the capture of a ship sailing from Jamaica to London during the Revolutionary War. On board, there was a turtle to be delivered to Lord North, the British Prime Minister. His name was “nicely cut into the shell.” . . .

Alexis: Tell me everything you know about the turtle’s great escape.

Mary: First, we have to talk about crawls. Once turtles were off-loaded from vessels, they were placed in a crawl. This was an enclosed fence-like structure that was partly underwater. It allowed innkeepers and merchants to keep the turtles alive until the moment they were dressed. But they weren’t the most secure containers. Storms and high tides…could flood crawls and give turtles the perfect opportunity for escape. Hopefully, this turtle made its way back to the Atlantic Ocean, but we’ll never know.

For more turtle content, here’s a P.D.F. download of Megan C. Hagseth’s doctoral dissertation ”Turtleizing Mariners: The Trans-Atlantic Trade and Consumption of Large Testudines in 16th- to 18th-Century Maritime Communities,” with numerous illustrations and newspaper extracts.

And here’s the Sea Control podcast episode in which Walker Mills interviews Dr. Sharika Crawford of the United States Naval Academy about her new book, The Last Turtlemen of the Caribbean: Waterscapes of Labor, Conservation and Boundary Making.

No comments:

Post a Comment