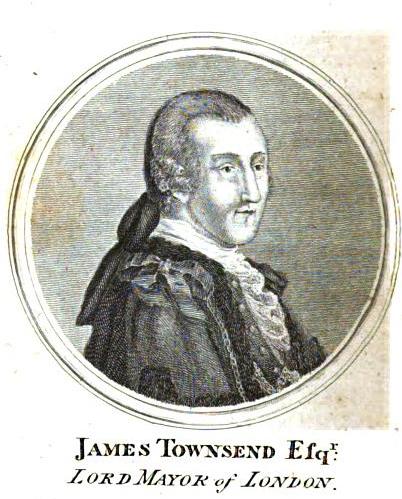

He was also a Member of Parliament for two stints, in 1767-74 and 1782-87. Unlike his father, who allied with George Grenville, Townsend became part of Lord Shelburne’s wing of the Whigs.

That put him on the left of British politics. The History of Parliament Online says of Townsend:

He made himself conspicuous in Parliament as an advocate of [John] Wilkes’s cause, contributed to his election expenses, and was a foundation member of the Bill of Rights Society. In 1771 he refused to pay the land tax on the ground that Middlesex was not represented in Parliament.That was, of course, an argument about taxation without representation within greater London itself.

In 1772 Townsend and John Horne Tooke broke with Wilkes while still remaining radical reformists. That year, Wilkes won more votes for Lord Mayor than anyone else, but the sheriff manipulated the voting process to put Townsend in office instead. That prompted riots against the new mayor, and he served only one term.

In October 2016 Notes and Queries discussed another aspect of Townsend’s life: one of his eight great-grandparents was African. In the part of eastern Africa that Europeans then called the Gold Coast, now Ghana, that woman reportedly had a child with a Dutch soldier.

That child, named Catherine, married James Phipps, a long-time employee of the Royal African Company of England. Toward the end of his life Phipps was the Captain-General of the company and Governor of Cape Coast Castle. In 1722 he lost those posts after being accused of embezzling and abusing power, and the following year he died. Phipps had wanted to bring his wife to Britain, even writing incentives for her to do so into his will, but she never left Africa. Instead, she became a major trader (and slaveowner) on the Gold Coast.

Back around 1715, the couple had sent two of their daughters, Bridget and Susanna, to Britain. Both girls, who had one African grandparent, were then around nine years old. Phipps’s family was surprised to receive “some issue” of him, but they duly sent those girls to a school in Battersea. Phipps’s wealth no doubt helped—there might have been something to those embezzlement charges.

In 1730 Bridget Phipps got married in the Fleet Prison, the venue probably chosen to evade parents and guardians. Her new husband was a London merchant and mining investor named Chauncy Townsend. They had many children, including James.

James Townsend’s legal papers in Britain reportedly contain no hint of his African great-grandmother. Nor does that ancestry appear to have come up in gossip about him as a politician. As Wolfram Latsch wrote in Notes and Queries and this blog post, “this fact was either unknown, or went unnoticed, or it was ignored.” His grandmother’s decision to stay away from Britain was probably a factor in how society perceived the Townsend family.

Latsch nonetheless identifies Townsend as “Britain’s first black MP” and the first black Lord Mayor of London. In one way he indeed was. But if no one knew about his ancestry, in another way he wasn’t.

No comments:

Post a Comment