For a presentation this week that didn’t come off, I picked out three extracts from the letters of young teenager Anna Green Winslow to her mother in Nova Scotia, showing her political awakening. She wrote between November 1771 and May 1773.

Richard Gridley, retired artillery colonel, explained the political factions to Anna.

As a girl, and an upper-class girl at that, Anna wasn’t supposed to demonstrate in the streets. But the Whig movement encouraged girls to participate in other ways, such as learning to spin so that local weavers could make more cloth so that local merchants didn’t have to import so much from Britain.

But Anna didn’t know how to spin.

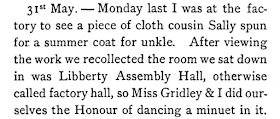

So she contented herself by visiting the Manufactory where her cousin Sally’s yarn had been woven into cloth, and doing a little dance there.

Anna could also participate in the movement as a consumer, choosing to buy more locally produced goods. In one letter she proudly described herself to her mother as a “daughter of liberty.”

I’m not sure how Anna’s family felt about the politics she was learning in Boston. Her father, Joshua Winslow, was more closely allied with royal officials. Later in 1773 he lucked out (he thought) in being named one of the East India Company’s tea consignees in Boston. But when the town mobilized against allowing that tea to be landed, he had to lie low in Marshfield. Eventually, he left Massachusetts as a Loyalist.

Anna Green Winslow remained in the state, living in Hingham, but she died in 1780. Alas, outside of those letters to her mother in 1771–1773 we have almost no sources about Anna’s life, so we don’t know how her political outlook changed after the Whigs made her father an enemy for agreeing to sell tea, and after the war began.

No comments:

Post a Comment