Those postings have now prompted two more substantial and quite different articles at the Journal of the American Revolution website.

First and more important, Larry Kidder wrote up the information he had collected about Pvt. Francis into the fullest biography of the man yet published. Here’s a taste of his portrayal of the young man’s decision to join the Continental Army outside Boston in the fall of 1775:

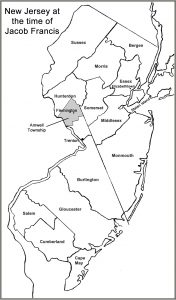

Not knowing his family surname, Jacob used the name of his third “time” owner, Minne Gulick or Hulick, an Amwell farmer of Dutch ancestry. However he felt about the ideals of liberty and independence driving the Revolution, as a free black who had experienced indentured servitude most of his life, he probably enlisted at least partly because he was a young man accustomed to authority, who needed a job, and who may also have been seeking adventure. When approaching the recruiting officer, though, he found that free blacks were not encouraged to enlist and often not accepted.That article fills out Pvt. Francis’s military experiences, particularly in his home state of New Jersey, and his life in the early republic. It’s a fine resource for people writing about African-American soldiers in the Revolution.

From the time Washington took command at Cambridge, he wanted to exclude black men from the army. Washington interpreted the fact that there already were “boys, deserters, & negroes” in the Massachusetts regiments as proof that not enough qualified white men were enlisting. At the very time Jacob enlisted in October, Washington was discussing with his officers and Congress whether or not blacks should be enlisted and, while not unanimous, most leaders wanted to eliminate black enlistment entirely. By October 31, just days after Jacob’s enlistment, Washington’s general orders stated that blacks should not be enlisted and this order was reinforced in November.

In addition, I assembled my postings about Jacob Francis’s anecdote into an article. While writing that, I found a third version of Francis’s story that a veteran of the siege of Boston named Simeon Locke reportedly told as an old man in Maine:

“‘I was a soldier in the army of the Revolution, and was detailed, with others, to build the breastworks on Dorchester Heights. A day or two after the works were begun, General Washington rode into the enclosure. I was a sentinel. Near me was a wheelbarrow and shovel; not far off was an idle soldier.I still hope someone will find the first published version of that story from 1839, the source of the earliest examples I’ve unearthed. That could reveal more about how it got passed along, and how funny tales old soldiers told each other became moral lessons for the new republic.

“‘“Why do you not work with the others?” asked Washington, addressing the soldier.

“‘“I am a corporal, sir,” he replied.

“‘The general immediately dismounted, and marched to the barrow, shovelled it full of sand, wheeled it to the breastworks, dumped his load, and returned the empty barrow to its place. Without uttering a word, he mounted his horse and rode away.’”

No comments:

Post a Comment