Russell took those remains home and showed them to neighbors. It’s unclear what evidence led to this conclusion, but people settled on the idea that those were “the bones of Revolutionary soldiers.”

Later that year the Medford selectmen paid the sexton Jacob Brooks $2.50 to bury the bones in a box in the town graveyard on Salem Street. But the town didn’t pay for that site to be marked.

[ADDENDUM: In 1855 Charles Brooks wrote in his town history:

Before the battle of Bunker Hill, General [John] Stark fixed his head-quarters at Medford, in the house built by Mr. Jonathan Wade, near the Medford House, on the east side of the street. After the battle, twenty-five of the general’s men, who had been killed, were brought here, and buried in the field, about fifty or sixty rods north of Gravelly Bridge. Their bones have been discovered recently.Stark was still a colonel in 1775. Other sources put his headquarters in the Isaac Royall House or the Admiral Vernon tavern, though of course he moved around. It’s not clear where Brooks received his information.]

Decades later, the Daughters of the American Revolution was eager to honor the graves of all Revolutionary War veterans. (Those markers were often credited to the Sons of the American Revolution, but it looks like the D.A.R. did a lot of the work involved.)

Eliza M. Gill, a town hall clerk, seretary of the Medford Historical Society, and founder of the local Sarah Bradlee Fulton chapter of the D.A.R., led the effort to identify all the local graves—including those not previously marked. It was well known that some regiments from New Hampshire had arrived in town early in the war and made their camps there.

A local man named Jacob Winslow Vining came forward with a story. He was Jacob Brooks’s grandson, born in 1848. Sometime in his youth, he had been helping his grandfather mow the Salem Street cemetery. The old sexton pointed out a bare spot, described burying the box of bones there, and told the boy to remember it. “Some time some one will want to know,” Grandpa Brooks reportedly said.

No one asked Vining about that information for decades, and he never told the story until Gill came looking for Revolutionary graves. Then he took her to that spot in the Salem Street cemetery.

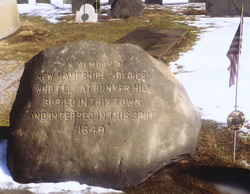

On behalf of the S.A.R. of New Hampshire, Alvin Burleigh of Plymouth picked out a local boulder and shipped it to Medford. The D.A.R. chapter arranged for that stone to be lettered, placed on the proper spot in the burying-ground, and dedicated on 29 Oct 1904, fifty-five years after the bones had been reinterred.

The boulder reads:

in memory ofThe 1904 ceremonies included a short “dedicatory exercise” on the site, an assembly at the Royall House hosted by Medford’s mayor, and a historical address by Eliza M. Gill.

New Hampshire soldiers

who fell at Bunker Hill

buried in this town

and interred in this spot

1849.

But were the remains buried under that boulder actually from casualties of Bunker Hill? Col. John Stark’s and James Reed’s regiments did suffer losses at that fight, probably two dozen dead. But how many of those bodies were they able to remove from the field? A few men did later die of their wounds. In addition, men from regiments stationed in Medford no doubt died in camp over the ensuing months.

It’s not clear how many bones John Russell dug up in 1849, or how people then determined that they came from the Revolution. But we can’t doubt the determination of the people of Medford in that year, and in 1904, to honor the men who came a long way to the siege lines and fell in the war.

No comments:

Post a Comment