The Harvard College Thanksgiving banquet in November 1787 ended badly. By the evening, window glass and wooden benches were lying on the ground outside the hall. That might have had something to do with how every student had brought a bottle of wine.

The Harvard College Thanksgiving banquet in November 1787 ended badly. By the evening, window glass and wooden benches were lying on the ground outside the hall. That might have had something to do with how every student had brought a bottle of wine.The Harvard faculty levied a ten-shilling fine on each student who had gone to that dinner and couldn’t prove he'd left before the destruction started. The administration then relented in the case of the sophomores, but not the seniors or juniors—including Charles Adams, class of 1789.

The fines went out in the quarterly bills at the start of 1788. So there was no way Charles could keep the bad news from his family (as he would try to do with financial reverses in the late 1790s).

At the time, Charles’s parents, John and Abigail, were still on a diplomatic mission in Britain. The task of looking after their sons had fallen to relatives: Abigail’s older sister Mary Cranch in Braintree; her younger sister Elizabeth Shaw and her husband John in Haverhill; and John’s cousin Dr. Cotton Tufts of Medford, who managed the family money.

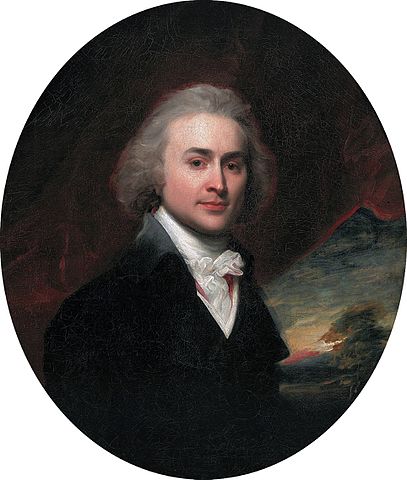

Eldest son John Quincy Adams (shown above) had graduated from Harvard the year before and gone to Newburyport to study law. On breaks he got together with both younger brothers. On 2 Feb 1788, after one such visit, John Q. wrote in his diary:

I had with Mr. Shaw some conversation upon the subject of the disorders which happened at College, in the course of the last quarter: his fears for my brothers are greater than mine: I am perswaded that Charles did not deserve the suspicions which were raised against him: and I have great hopes that his future conduct, will convince the governors of the University, that he was innocent.The Rev. John Shaw had tutored both Charles and Thomas Boylston Adams to prepare them for college, as well as other boys. (Including Charles’s first roommate or “chum,” who’d gotten into worse trouble—but I’ll talk about that some other time.) Shaw was clearly worried about Charles’s behavior while John Q. tried to stand up for him.

Two weeks later John wrote to Dr. Tufts for some spending money, noting that he’d asked Charles to pass on the request but, well, “I am apprehensive he forgot to deliver my message.” Like many oldest sons, he seems to have felt both protective of his little brothers and convinced they were incurable idiots.

John Q. went on with more hopeful comments about the situation:

The riotous ungovernable spirit, which appeared among the students at the university in the course of the last quarter gave me great anxiety; particularly as I understood, that one of my brothers, was suspected of having been active in exciting disturbances; but from his own declarations and from the opinion I have of his disposition, I hope those suspicions, were without foundation—I conversed with him largely upon the subject, and hope, his conduct in future, will be such as to remove, every unfavourable impression.Others in the family were adding their voices, perhaps less optimistically. The next day, 17 February, Aunt Elizabeth wrote to Aunt Mary:

I long to hear from Charles & Thomas I charged them to write to me— I do not know that Mr Shaw & I could have given them better advice if they had been our own Sons— I hope they will conduct agreeable to it—& be wiser than they have been, & more cautious of abusing Government, for what they from choice suffer—the Ten shillings penalty, I mean—As I wrote a couple of days ago, I think the record shows that only Charles had been fined the ten shillings and Tommy still had a near-spotless record at college. But he was the little brother, and the family didn’t want Charles to lead him astray.

Unfortunately, all those admonitions didn’t keep Charles out of trouble in his senior year.

TOMORROW: A rough winter in Cambridge.

No comments:

Post a Comment