According to a reprint in Niles’s Weekly Register the following month, it said:

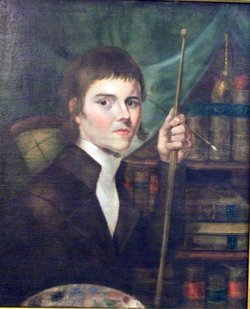

I stepped into the house of a friend the other evening, and he told me, that in rummaging over some old drawers he found a curiosity. It was indeed very interesting and curious, to me at least, I dare say it would be so to you, reader.Publishers were intrigued. Some made inquiry and discovered the man who possessed the hand-drawn map was Jacob Cist of Wilkes-Barre, a postmaster, artist, naturalist, and promoter of anthracite coal (shown above).

The thing referred to was a view or plan of the battle of Bunker’s hill, taken by a British officer at the time, who was in the engagement. The execution was in a style of uncommon neatness; and as far as it was possible for me to judge, extremely and minutely accurate.

The references were numerous and particular. The place of landing of the British was laid down—each regiment numbered—the artillery and light infantry particularly designated—the precise line of march pointed out—the situation of the American posts of defence, even to a barn, and the particular force that attacked the barn, laid down.

The place of the greatest carnage or loss of the British—the two vessels that were moored to annoy our people—the battery that played upon our fortifications—the line of retreat and the situation of the craft stationed to cut off our troops, the situation of the commanding officer of the British; and indeed every thing that could tend to give a full and clear idea of the situation and movements of the parties.

On looking over this map deep and strong emotions were excited—pride at the glorious defence made by our undisciplined American yeomanry, against the best regular forces of the old world—patriotism, by considering the spirit and devotion of our militia in defence of freedom and their country—pity for the suffering of the number who fell, and admiration of the dauntless spirit of the assailants and the assailed.

At the same time it was impossible to repress the smile, half in anger and half in mirth at the repetition of the word “Rebels” which occurred so often in the delineation. It brought to our minds the battle of the kegs, where the frequent use of the odious and contemptible expression is so handsomely ridiculed.

This probably is the only accurate plan of that memorable battle, in existence. It ought certainly to be engraved, and the copies multiplied, together with a correct account of the engagement, and to be in the possession of every friend to the liberties of the country.

A man named I. A. Chapham copied Cist’s map and brought it to Philadelphia, where an engraving firm produced prints for the February issue of the Analectic Magazine. Here’s a digitized image from the Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

The next month, the Port Folio published a second engraving copied from the competing magazine with red marks overlaid to show corrections by Gen. Henry Dearborn, a veteran of the battle. Here’s an image of that map. Dearborn’s accompanying article ignited a feud with descendants of Gen. Israel Putnam and others that lasted for years.

The publication of the Analectic engraving revealed the name of the British officer who had sketched the map: Lt. Henry DeBerniere, misidentified as an officer of the 14th (rather than 10th) Regiment.

The manuscript sketch doesn’t survive. Neither does any clue about how DeBerniere’s sketch came into the hands of Jacob Cist. He was born in Philadelphia in 1782, and we know DeBerniere was in that city with the British army in 1777-78. Had the officer left the sketch behind, just as he had left his written manuscripts in Boston?

Cist also worked for the U.S. Post Office Department in Washington, D.C., from 1800 to 1808 before settling in Wilkes-Barre. Did he collect the map as a curiosity? Was he really just “rummaging over some old drawers” when he realized what it was?

The provenance will remain a mystery. Similarly, we have no idea how the historian Peter Force came by DeBerniere’s map of the Massachusetts countryside now in the Library of Congress collection. But Lt. DeBerniere’s map has been one of the main sources for every printed map of the Battle of Bunker Hill since 1818.

COMING UP: The post-Revolutionary career of Henry DeBerniere.

No comments:

Post a Comment