I also promised a look at DeBerniere’s career after the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, which he helped to make happen when and where it did.

My research was complicated and delayed by what David C. Agnew wrote about the DeBerniere family in the genealogical reference book Protestant Exiles from France, Chiefly in the Reign of Louis XIV (1874):

Jean Antoine de Bernière…came over to Ireland. He is reputed by the present French representatives of the family to have been the chief of his name. For conscience sake he left the estate of Bernières near Caen; he is called in the Crommelin Pedigree, “gentilhomme d’aupres d’Alencon.”If that birthyear is correct, then Ens. Henry DeBerniere was only twelve or thirteen years old when he scouted the roads to Worcester and Concord, drew his maps, and wrote his report. That narrative doesn’t read like the writing of a young teenager, and there’s no indication that the people DeBerniere met perceived him as unusually young.

The refugee served under the Earl of Galway at the battle of Almanza; he was wounded and lost a hand; his life was also in danger, but by means of an ancient ring which he wore, and which had been the gift of a French king to one of his ancestors, he was recognised by a tenant on the Bernières lands and received quarter.

On his return to Ireland he married Madeleine Crommelin, only daughter of the great Crommelin. His grandson was Captain [Louis Crommelin] De Bernière of the 30th Regiment, who died from exhaustion after the siege of Senegal in 1762, leaving an only son and heir, Henry Abraham Crommelin de Bernière, who rose to be a Major-General in the British army.

Major-General de Bernière, was born in 1762, and joined the 10th regiment in 1777, at once entering upon active service in America under General [John] Burgoyne.

Furthermore, Agnew was obviously wrong about when Henry DeBerniere joined the British army. He was serving in Boston in early 1775, so he probably enlisted before that. Plus, he wasn’t his father’s “only son.”

This webpage about the Crommelin family offers different and seemingly more reliable information, though it doesn’t cite sources:

In 1739 Louis Bernière married Elinor Donlevy, sister-in-law of the Bishop of Dromore, Louis was also a soldier and saw service in Canada and Senegal where he became ill and was sent home on furlough. He never reached Lisburn, dying at sea in 1762. His wife had died previously in 1759 and their children were taken by relatives to be brought up.Since Henry’s mother died in 1759, he must have been at least sixteen and quite possibly a little older when he did his scouting missions. Not too much older since ensign was the most junior officer’s rank, but at least in his late teens.

The elder son, John Anthony De Bernière born in Lisburn in 1744, was sent to his aunt, the wife of Bishop Marlay, and eventually entered the army. The younger son [Henry] went to Dublin, to the home of Paul Mangin, and in time he also became a soldier, serving in America and France and rising to the rank of Brigadier.

In the 1890s Washington Chauncey Ford published a compilation of “British Officers in America, 1754–1774” in the New England Historical Genealogical Register. It included these listings of commissions:

Birniere, Henry / Ensign / [blank] / 22 August, 1770.Because of the contradictory information, I had to consider the possibility that there were two men named Henry DeBerniere, perhaps cousins, serving in the British army at the same time. But the Army Lists published in the 1770s and 1780s show only one.

Ensign / 10[th Regiment] / 14 September, 1779.

Birniere, John de / Ensign / 55 / 22 November, 1755.

Lieut. / 44 / 9 August, 1760.

Lieut. / 18 / 4 February, 1769.

In the end, I concluded that Henry DeBerniere followed his father and his older brother John into the army in 1770. It looks like the DeBerniere family had connections and a military pedigree but not a lot of money, plus Henry was the younger son. His army career was probably slower than other officers because he couldn’t buy higher ranks as easily.

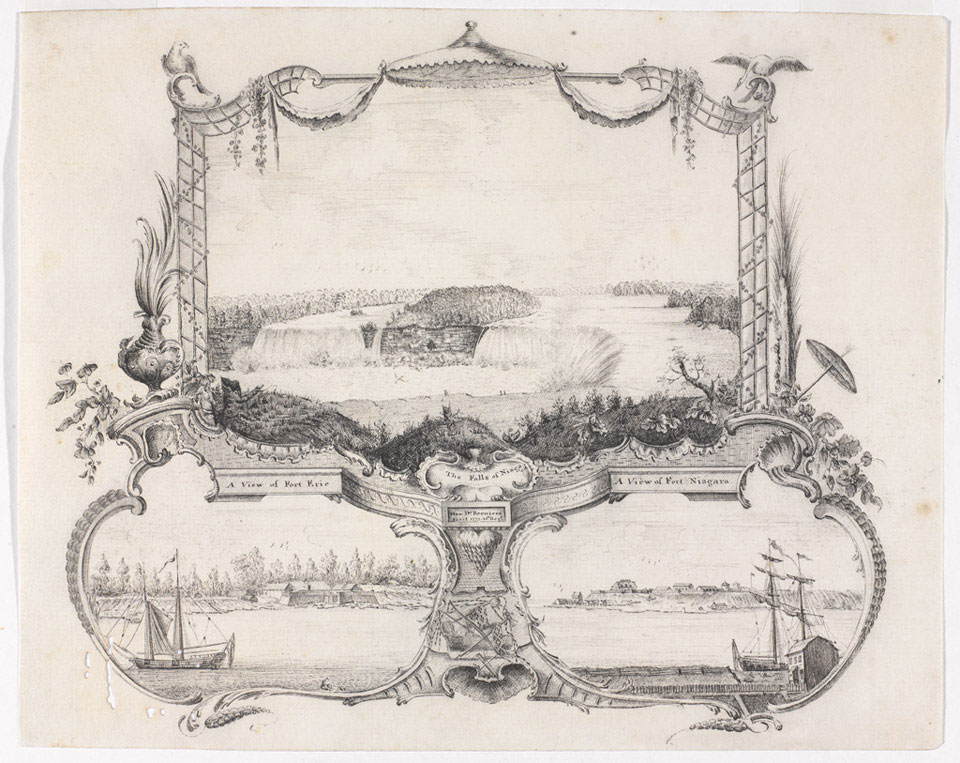

In 1773 the 10th Regiment was stationed along the Niagara River. And we have Ens. DeBerniere’s sketches of Fort Erie, Fort Niagara, and Niagara Falls from that year. Those appear above, courtesy of the U.K.’s National Army Museum. I found another statement saying he probably drew a map of Detroit around the same time.

Thus, by early 1775 Ens. DeBerniere had nearly five years of experience in the army and in North America, and was a practiced draftsman.

TOMORROW: DeBerniere after 1775.

John Anthony DeBerniere’s death record says he was 67 years and 6 months old when he died in May 1812. That means he was born near the end of the year 1744.

ReplyDeleteHow does that square with his commission as an ensign being dated November 1755? It wasn’t uncommon for military families—and the DeBerniere brothers’ father was serving at that point—to put their sons down for commissions at a very young age. They didn’t actually start to serve until they were older. But it still looks like John DeBerniere was at work in the 44th Regiment by his mid-teens.

I suspect Henry’s first commission didn’t come when he was eight, or even eleven, because his father wasn’t alive to obtain it. Instead, he probably made the decision to enter the army a few years later.