Stedman was born into a military family, his father a Scotsman who had joined the army of the Dutch Republic and his mother reportedly a Dutch noblewoman.

At twenty-seven years old, feeling the need for both money and adventure, Stedman volunteered to command a corps fighting “Maroons,” or people of African descent who had freed themselves from slavery and were challenging the white colonial society.

Stedman arrived in Suriname, a South American colony that really functioned as part of the West Indies, in February 1773. He stayed for four years, fighting Maroons and his boss with equal fervor.

Gaddy explained:

In his diary, Stedman described the Maroons, the armed tribes he was fighting, the lush landscape and the indigenous Arawaks who lived in the dense tropical jungle. He also wrote about his relationship with an enslaved woman named Joanna, the many sexual encounters he had and the lives of both masters and the enslaved. What he did, the music he heard, the unusual foods he ate and the indigenous plants he saw — everything was recorded in his journal. In addition, he collected “curiosities” — now part of the collection at the Museum Volkenkunde (the National Museum of Ethnology) in Leiden, the Netherlands — and painted vivid watercolors of scenes from Suriname.In 1988 Richard and Sally Price finally created an edition that compared Stedman’s manuscript diary, which ended up at the University of Minnesota, against the published version. The original had a lot more sex, it seems.

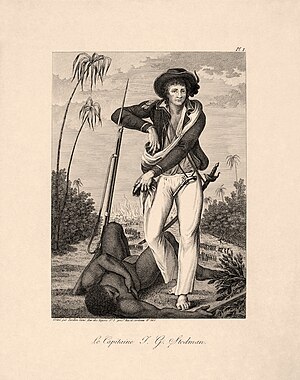

When he returned to the Netherlands in 1777, Stedman set to crafting a story from his diary entries, eventually selling the rights to Joseph Johnson, a London publisher. Starting in 1790, Johnson devoted six years to transforming Stedman’s watercolors into engravings — he commissioned William Blake to produce several plates — that could be reproduced for the book.

That book — Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition, Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana, on the Wild Coast of South America — came out in 1796 and became an immediate popular success. While slavery existed in Europe, large plantations did not, and Stedman’s evocative, at times graphic account of both free and enslaved lives was richly illuminating to people across the Continent. “[Stedman’s book] was fundamental to people’s understanding of slavery” in the late 18th and early 19th century, says Karwan Fatah-Black, assistant professor of history at Leiden University in the Netherlands. Narrative was quickly translated into Dutch, Swedish, Italian, French and German, and became an international best-seller that would ultimately appear in 25 editions.

It was the kind of overnight success that would have thrilled most authors. But Stedman was enraged. It turned out that Joseph Johnson had secretly hired an editor to revise the original text and then published a version Stedman condemned as an outright distortion. “My book was printed full of lies and nonsense,” he wrote to his sister-in-law, and he claimed to have burned 2,000 copies.

Interestingly, the editing also made Stedman out to be more supportive of slavery than he really was. (It sounds like he was a bit cynical about everything.) Nonetheless, Stedman’s account of the slave society—perhaps because it wasn’t about a British colony—became one of the foundational texts of the British anti-slavery movement.

The Wikipedia article on Stedman is impressively detailed and worth reading alongside Gaddy’s.

No comments:

Post a Comment