On Saturday, 5 July, the

Longfellow House–Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site will host the

Sestercentennial commemoration of Gen.

George Washington taking command of the

Continental Army.

Washington arrived in

Cambridge on the afternoon of 2 July and assumed command from Gen.

Artemas Ward. Nineteenth-century tradition held that 3 July was the crucial day, imagining the new commander reviewing all his troops on Cambridge common, but that was at best an

exaggeration. The 4th is of course claimed by an event from 1776. So Saturday the 5th is the most convenient date for a celebration this year.

Here’s the

“Headquarters of a Revolution” schedule. Unless stated otherwise, all of these events start at 105 Brattle Street, the Longfellow–Washington site. Some offerings overlap, so it’s not possible to see everything. The talks are about half an hour long, the house tours almost an hour, the walking tours more like ninety minutes. Folks who need air conditioning or shelter from rain will no doubt prefer the talks and house tours.

10:00 A.M. to 3:00 P.M.The New Generalissimo

John Koopman and Quinton Castle

On the mansion’s lawn, visitors can meet and talk with living historians portraying Gen. George Washington (Koopman) and his body servant,

William Lee (Castle), as they assess the

siege, the Continental Army, the political situation, and living arrangements in Cambridge. Photo opportunities.

10:15 A.M. talk in the Longfellow Carriage HouseGet Ready with Martha

Sandy Spector

Learn all about the

clothing of 1775 as

Mrs. Washington finishes dressing for her day. There will be some stories and some gossip, too! Spector is a Boston-based historian, researcher, and interpreter known for bringing emotional depth, humanity, and a sense of humor to her portrayal of Martha Washington.

10:30 A.M. walking tour Children of the Revolution: Boys & Girls in Cambridge during the Siege of Boston

J. L. Bell

Meet at the mansion’s driveway for a walk around the Tory Row neighborhood and Harvard Square viewing sites and hearing stories of

young people caught up in the opening of the Revolutionary War:

Loyalists forced from their homes, soldiers in their teens or younger, war refugees, and

enslaved children seizing their own liberty.

11:00 A.M. talk in the Longfellow Carriage House

The Revolutionary War Diary of Moses Sleeper

Kate Hanson Plass

An almost-anonymous journal in the Longfellow–Washington site’s collection provides a look at daily life in the Continental Army in Cambridge. Cpl.

Moses Sleeper spent most of the Siege of Boston encamped and building barracks around Prospect Hill. Hanson Plass, the Longfellow House Archivist, explains how Sleeper’s perspective adds to our understanding of the experience of the soldiers under General Washington’s command.

11:30 A.M. house tour

Deep Dive: Headquarters of a Revolution

National Park Service staff

Explore Gen. George Washington’s first headquarters of the American Revolution. That mansion became a testing ground for many of the ideals, institutions, and questions that still define our nation. This conversational tour explores Cambridge Headquarters as a hub of revolutionary activity, where generals, enslaved people, paid laborers, poets, Indigenous diplomats, politicians, and soldiers shaped history—and how later generations would shape its memory.

12:30 P.M. talk in the Longfellow Carriage House

Washington in the Native Northeast

Dr. Ben Pokross

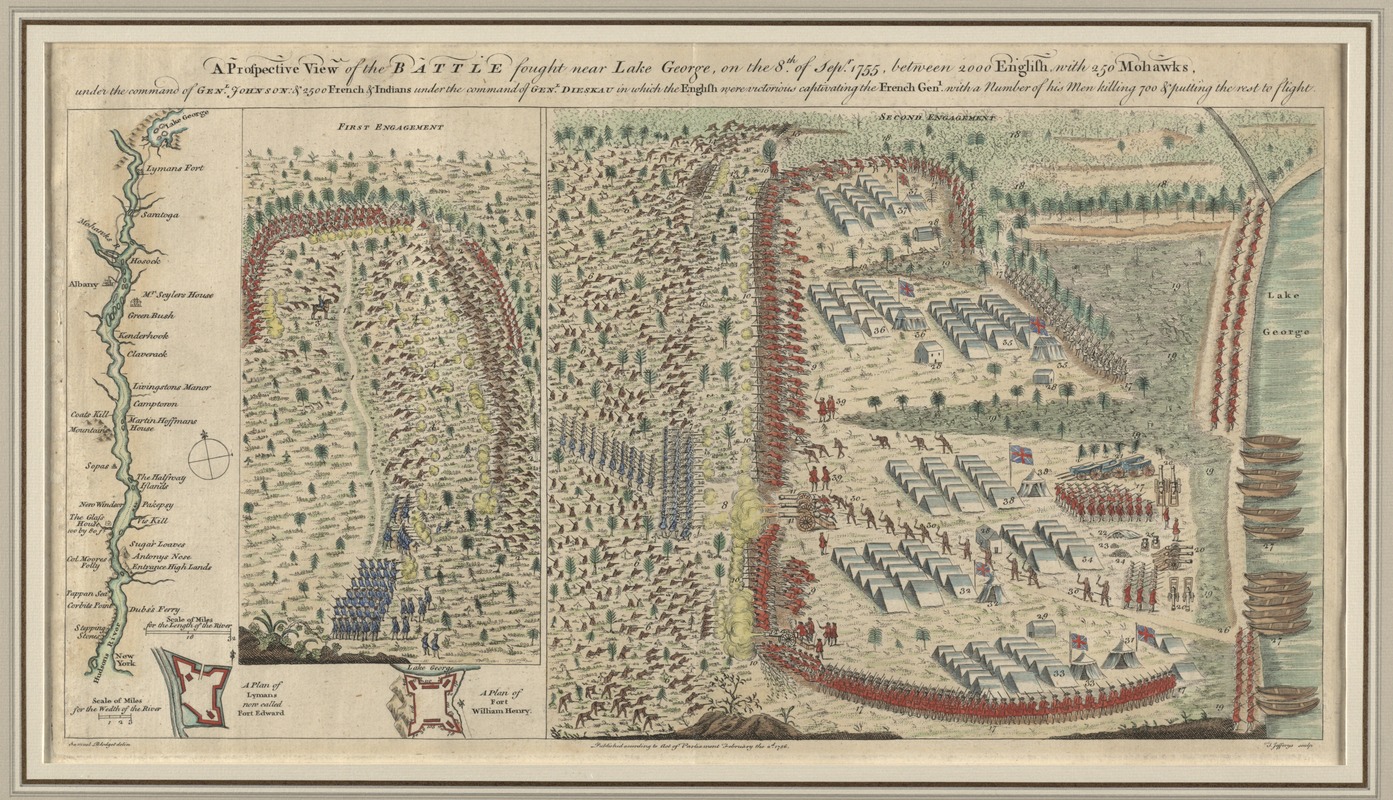

This talk describes George Washington’s interactions with

Indigenous people while he lived in the Vassall House. After a look back on Washington’s experiences as a surveyor in the Ohio River Valley, the presentation will focus on his

diplomatic encounters with Abenaki, Haudenosaunee, Passamaquody, and Maliseet peoples, among others, during the Siege of Boston. Ben Pokross was a Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow at the Longfellow–Washington site researching its Indigenous history. In the fall, he will be a Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Trinity College in Hartford.

1:15 P.M. talk in the Longfellow Carriage House

On Managing a Headquarters that is Also a Household

Sandy Spector

Martha Washington made her own arrival in Cambridge in December 1775 and stayed until April, setting the pattern she would follow throughout the Revolutionary War: she spent every winter with her husband and the army, and during campaign season usually remained as close as she safely could. Spector describes how the commander’s wife maintained a genteel household in the midst of war.

1:30 P.M. walking tour

Cambridge as a Seat of Civil War

J. L. Bell

Meet at the Washington Gate on Cambridge Common. This tour explores how the Cambridge community split on

religious, political, and class lines between 1760 and 1775, culminating in a

militia uprising in September 1774 and the outbreak of actual war in April 1775. Hear how the wealthy and congenial Tory Row neighborhood fell apart and became a stretch of military barracks and hospitals.

2:00 P.M. talk in the Longfellow Carriage House

Phillis and George: Thoughts on Letter-Writing, Power, and Self-Representation

Dr. Nicole Aljoe

One famous event during Washington’s time in Cambridge was his exchange of letters with

Phillis Wheatley, the young poet who had been kidnapped into slavery. Aljoe, Professor of English and Africana Studies at Northeastern University, explores this encounter in context. She is co-Director of The Early Caribbean Digital Archive and Mapping Black London digital project, Director of the Early Black Boston Digital Almanac, and author of multiple books and articles.

2:30 P.M. house tour

Deep Dive: Headquarters of a Revolution

National Park Service staff

See above.

2:45 P.M. talk in the Longfellow Carriage House

Cambridge’s Black Community, 1775

Dr. Caitlin DeAngelis Hopkins

The American Revolution was a time of both possibility and peril for Black residents of Cambridge. Enslaved people could pursue their liberty but faced the threats of family separation, deadly epidemics, and violence. Whether moving far away, taking jobs at Washington’s Headquarters, or making complex

legal arguments to claim pieces of their enslavers’ estates, Black residents used their knowledge and networks to protect themselves and their families. Hopkins is working with the descendants of

Cuba and

Anthony Vassall to document the Black history of 105 Brattle. She holds a Ph.D. from Harvard and was formerly the head researcher for the Harvard and the Legacies of Slavery Project.

This commemoration is funded by Eastern National, a non-profit partner of the National Park Service. It’s supported by friendly organizations like History Cambridge and the Friends of Longfellow House–Washington’s Headquarters.

.jpg/220px-Admiral_Sir_Alexander_Inglis_Cochrane_(1758%E2%80%931832).jpg)