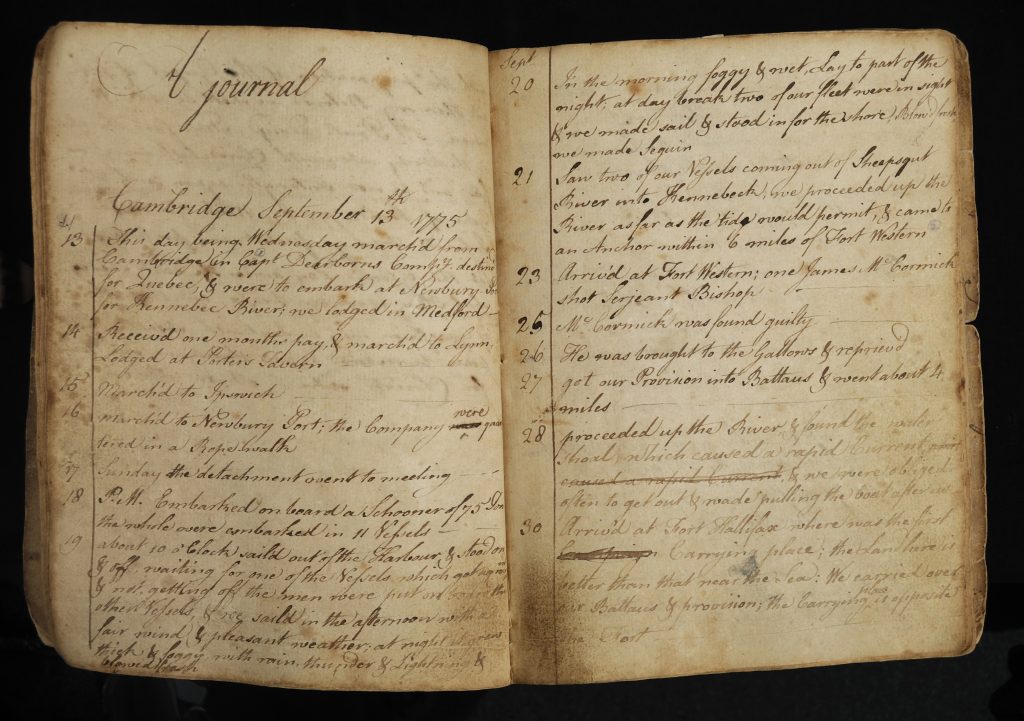

Pvt. James Melvin’s Journal in Manuscript

The American Revolution Institute, part of the Anderson House museum and library of the Society of the Cincinnati, has acquired the manuscript journal of Pvt. James Melvin.

Melvin was born in Concord in 1749, according to John Melvin of Charlestown and Concord, Mass. and His Descendants (1905), but different calculations of his age suggest he was born as late as 1753. James’s father moved the family to Chester, Nova Scotia. After his father’s remarriage and an unhappy indenture, James returned to Concord to live with an older brother. He mustered for the April 1775 alarm and enlisted in the army from yet another Massachusetts town, Hubbardston.

In the summer of 1775, Melvin joined Col. Benedict Arnold’s expedition through Maine to Québec. His journal covers that journey from the soldiers’ departure in September through imprisonment in Canada to freedom on parole in August 1776.

Pvt. Melvin’s journal was transcribed and published in 1857. That text was issued twice more on its own, most recently in 1902. The total number of copies from those editions was 450.

Kenneth Roberts reprinted the whole Melvin journal in March to Quebec while also suggesting its text had been copied and developed from the diary of another soldier, Moses Kimball.

However, Stephen Darley collected all the known journals of the Quebec mission in Voices from a Wilderness Expedition (2011). He reports the Melvin and Kimball journals each have material not found in the other, with Melvin’s continuing for months after its supposed source. On the other hand, Darley says the Melvin diary offers “no special content,” meaning no historical events that other diaries don’t already document.

The fact that so many men on the Quebec mission kept journals shows how significant they and their descendants felt that undertaking was. Some of those diaries are near copies of others while some are quite individual. Some documents appear to have been the actual papers men carried on the trek while others are later copies.

After returning to the U.S. of A. in late 1776, Melvin remained in the army, stationed for the most part at the artillery laboratory in Springfield, making gunpowder. He married a widow there in 1778 after they conceived a child and lived the rest of his life in Springfield and Chester, Massachusetts. Melvin lived at least until 1828, when he unsuccessfully applied for a pension.

Melvin’s record was still in her family’s hands when it was first published, but then it went underground—until now. The American Revolution Institute plans to digitize the manuscript and share the images. It reports the manuscript also contains a couple of essays titled “Treatise upon Air” and “An Explanation of Scripture Taken from the Epistle of St. Paul the Apostle to the Gallations.” There’s no report of text on the Québec march that we haven’t seen before, but we’ll see Melvin’s account in its oldest surviving form.

Melvin was born in Concord in 1749, according to John Melvin of Charlestown and Concord, Mass. and His Descendants (1905), but different calculations of his age suggest he was born as late as 1753. James’s father moved the family to Chester, Nova Scotia. After his father’s remarriage and an unhappy indenture, James returned to Concord to live with an older brother. He mustered for the April 1775 alarm and enlisted in the army from yet another Massachusetts town, Hubbardston.

In the summer of 1775, Melvin joined Col. Benedict Arnold’s expedition through Maine to Québec. His journal covers that journey from the soldiers’ departure in September through imprisonment in Canada to freedom on parole in August 1776.

Pvt. Melvin’s journal was transcribed and published in 1857. That text was issued twice more on its own, most recently in 1902. The total number of copies from those editions was 450.

Kenneth Roberts reprinted the whole Melvin journal in March to Quebec while also suggesting its text had been copied and developed from the diary of another soldier, Moses Kimball.

However, Stephen Darley collected all the known journals of the Quebec mission in Voices from a Wilderness Expedition (2011). He reports the Melvin and Kimball journals each have material not found in the other, with Melvin’s continuing for months after its supposed source. On the other hand, Darley says the Melvin diary offers “no special content,” meaning no historical events that other diaries don’t already document.

The fact that so many men on the Quebec mission kept journals shows how significant they and their descendants felt that undertaking was. Some of those diaries are near copies of others while some are quite individual. Some documents appear to have been the actual papers men carried on the trek while others are later copies.

After returning to the U.S. of A. in late 1776, Melvin remained in the army, stationed for the most part at the artillery laboratory in Springfield, making gunpowder. He married a widow there in 1778 after they conceived a child and lived the rest of his life in Springfield and Chester, Massachusetts. Melvin lived at least until 1828, when he unsuccessfully applied for a pension.

Melvin’s record was still in her family’s hands when it was first published, but then it went underground—until now. The American Revolution Institute plans to digitize the manuscript and share the images. It reports the manuscript also contains a couple of essays titled “Treatise upon Air” and “An Explanation of Scripture Taken from the Epistle of St. Paul the Apostle to the Gallations.” There’s no report of text on the Québec march that we haven’t seen before, but we’ll see Melvin’s account in its oldest surviving form.