“They shou’d have been obliged to have eat all the Bad Butter”

The unrest started with a protest against rancid butter in autumn 1766. According to one account, on 23 September student Asa Dunbar told the college’s senior fellow, Belcher Hancock, “Behold our butter stinketh and we cannot eat thereof!”

That quotation appears in a telling of the event that’s entirely in mock Biblical language, so I’m not convinced those were Dunbar’s actual words.

Whatever Dunbar said, the faculty deemed his behavior “a very great Misdemeanr. by an high act of Disobedience.” They demanded an apology and demoted him to the bottom of his class.

Predictably, instead of stopping the protests, that harsh punishment caused more discontent. Most of the undergraduates had a meeting that night. Then more bad butter was served the next morning. When more boys complained, their tutors replied by saying that morning’s butter was “pretty good—much better than they had frequently been served with.”

At that point, senior Daniel Johnson (1747–1777) stood up and started walking out of the dining hall, before the faculty read the prayer of thanks and dismissed the students. A second later, as they had agreed the night before, almost all the undergraduates stood and followed him. Only three upperclassmen and a few freshmen remained in the hall. Outside in the yard, the students huzzahed and fanned out into Cambridge to find breakfast.

The students didn’t know that the faculty had appointed a committee “to examine the Condition of the Stewards Butter & condemn what they tho’t not proper to be offerd to the Scholars.” Later that day, that committee rejected one barrel and six firkins of butter and deemed four firkins suitable “for Sauce only.” The tutors agreed that the butter was bad, and indeed they’d made their own complaints to college steward Jonathan Hastings.

The bigger problem, as far as the college administration was concerned, was that the undergraduates had not “presented a Petition to those in the im̄ediate Governmt. of the College, to have this Grievance redress’d.” Instead, their large meetings and collective actions constituted “a Breach of the Law relating to Combinations.”

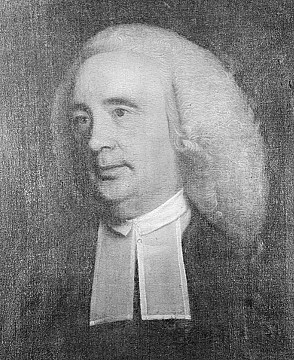

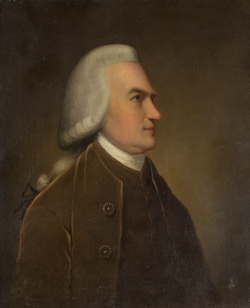

That evening, after prayers, the long-tenured college president, the Rev. Samuel Holyoke (shown above), announced the butter committee’s findings. But he demanded that students confess they had broken college rules while promising that he might remit their punishment.

Prof. Samuel Wigglesworth summoned Daniel Johnson, a former tutee, and asked him to cooperate to avoid being rusticated (and presumably set an example for the rest of the student body). Johnson refused to sign any acknowledgement of guilt, insisting that the students had no other way of gaining redress.

On 26 September, more faculty members met with Johnson, asking him to sign, and get his classmates to sign, an admission “That some of our late Proceedings, in Order to procure Relief from a Grievance we have lain under, were irregular & unconstitutional.”

Johnson refused to sign any confession. Furthermore, he said most of the undergraduates would leave the college before signing any confession.

This wasn’t a confession, the faculty insisted; it was merely an expression of sorrow. Johnson said he had nothing to express sorrow about. He repeated that the students’ method of protest was the only way they could be heard. That response echoed what American Whigs were saying to the Crown.

The discussion continued to go round and round about proper procedure:

He was told, that the College Law prescrib’d, First an Application to the Presdt. & Tutrs., Then to the Corporation & Overseers.Having made that promise, the faculty asked Johnson to read their language to his fellow students. According to William C. Lane, the senior said he’d “be afraid to enter the College Yard should it be known that he had such a paper about him, for he should either have his limbs broke or be hissed out of the Yard.”

He said, if they had proceeded in that Manner, they shou’d have been obliged to have eat all the Bad Butter before They cou’d have procur’d Redress.

Upon this he was told, That upon emergent Occasions [i.e., in emergencies] The Presdt. call’d a Meeting of the Corporation im̄ediately & that if Theyhad made a proper Application, There might probably have been a Meeting of the Corporation on ye next Day.

Increasingly desperate, the faculty invited Johnson and his fellow scholars to draft their own “Declaration of Grievances and the Reason of their Conduct” and sign that. And if anyone objected to signing that, he could speak personally to the college president.

Half an hour later, President Holyoke was about to leave his house to lead evening prayers. Almost the whole student body was on his doorstep asking to explain their objections to him.

TOMORROW: The controversy churns.