A couple of weeks back I

dissected the records of

Josiah Quincy, Jr.’s 1774–75 visit to Britain, and in those postings I now believe I misidentified a man.

I think I erred because of an error in the notes to

Quincy’s London journal as edited by Daniel R. Coquillette and Neil Longley York for the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. And I think Coquillette and York erred because of an error by Josiah Quincy, Jr., himself.

So let’s go back to the start of the eighteenth century. When

Benjamin Franklin was a

boy, he was already an uncle. That was because little Ben was the youngest son of the second marriage of Josiah Franklin (1657–1745). That man had had seven children by his first wife, starting in 1678 before the family moved to Massachusetts.

Baby Ben was thus almost thirty years younger than his oldest half-sibling, and the earliest half-siblings married and had children as he was growing up. When Ben was six years old, his half-sister Anne (1687–1729) married William Harris, and when Ben was twelve that couple had a baby named Grace (1718–1790). Grace was thus a niece of young Benjamin Franklin.

In 1746 Grace Harris married a man named

Jonathan Williams. At this point the situation becomes confusing because there were

two prominent men named Jonathan Williams in mid-1700s Boston, and authors have amalgamated the records of their lives. As a result, at Founders Online the editors of the Franklin Papers and the Adams Papers disagreed on when the Jonathan Williams who married Grace Harris was born and died.

The Adams Papers at one point said that man “(d[ied]. 1788),” probably based on a report in the

Massachusetts Centinel of 29 Mar 1788 that “Deacon Jonathan Williams” had just died at age 88. The records of the First Meetinghouse say “Jonathan Williams (Son of the late Deacon Williams)” was himself chosen a deacon in 1737, and he appeared in those papers through 1776. However, that deacon’s widow was named Sarah, according to her own death notice in the 16 Sept 1789

Centinel.

On 14 Apr 1790 the

Centinel reported the death of “Mrs. GRACE WILLIAMS, aged 71, the consort of Jonathan Williams, Esq. of this town, merchant.” That woman’s given name indicates she was Franklin’s niece. Her husband survived her for a few years, moving to his son’s home at Mount Pleasant near Philadelphia. Then the 1 Oct 1796

Columbian Centinel reported the death there of “Jonathan Williams, Sr., formerly a reputable merchant in this town [Boston].”

Therefore, after going back and forth on the question many times, I’ve decided that the Franklin Papers were correct in saying that the Jonathan Williams connected to the Franklin family lived “1719–1796.” (The

Adams Family Correspondence volumes adopted these dates, too.) I can’t find confirmation for the birth year but can say that, contrary to many profiles of him, this man

wasn’t the son of the Deacon Jonathan Williams who appeared in

Samuel Sewall’s diary.

The Jonathan Williams who married Grace Harris was a successful merchant and Boston

town official, thus earning the suffix “Esq.” As a Whig, he served on some town committees and in November 1773

moderated of one of the extra-legal tea meetings in

Old South.

Franklin used this merchant Jonathan Williams as his business agent in Boston, referring to him as

“Cousin Williams” and

“Loving Cousin” since our language doesn’t have a specific term for a niece’s husband. However, when he was feeling conspiracy-minded,

Thomas Hutchinson described that Williams as “a Nephew of Doctor F———ds,” making the relationship closer than it really was.

Now here’s where it gets more confusing. Jonathan Williams, Esq., had a brother named

John (d. 1791). In 1767

Franklin told his son

William that this man was “brother to our cousin Williams of Boston.” John Williams went to work for the

Customs service in the late 1760s, though he ended up feuding with his superiors and spent most of the 1770s trying to go over their heads in London.

And here’s where it gets even more confusing. Both brothers, Jonathan Williams and John Williams, had sons in the 1750s whom they named Jonathan. So did their sister Mary, who married

Samuel Austin. Two of those three first cousins named Jonathan studied

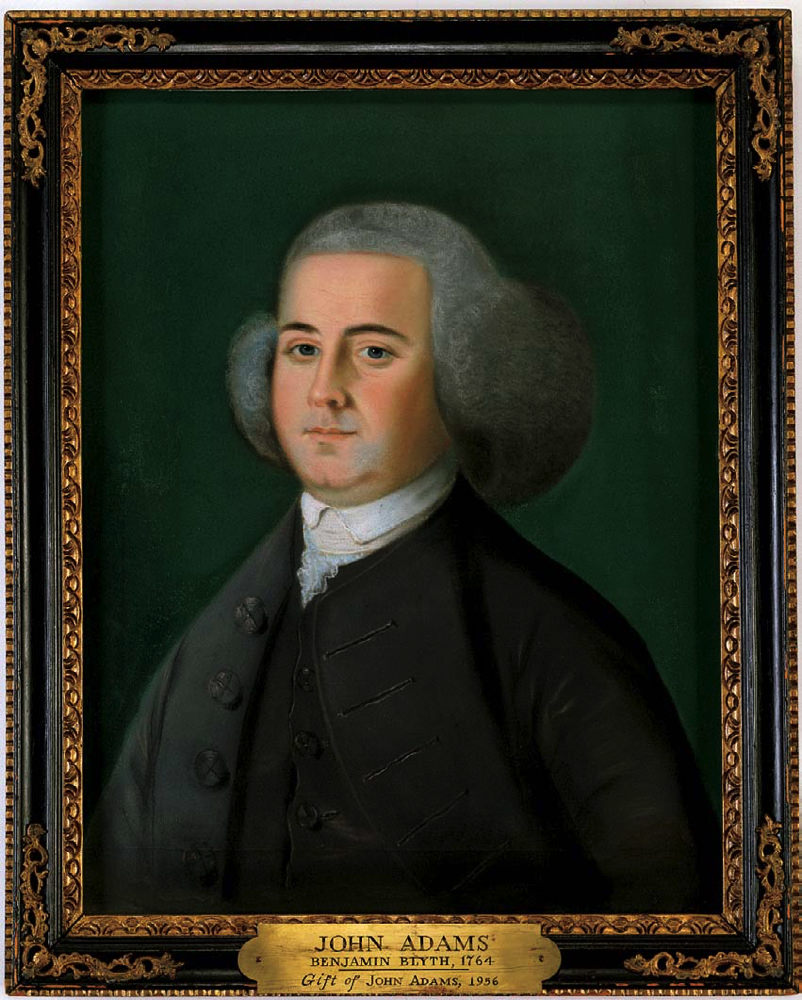

law under

John Adams. A different two spent years in

France during the Revolutionary War. And two died during the war.

So who met with Josiah Quincy in London in 1774?

TOMORROW: Sorting through the Jonathan Williamses (and John).