The Outcome of Harvard’s “Butter Rebellion”

Certainly the undergraduates did end their action on 11 October, nearly all of them signing the confession dictated by the faculty.

However, we shouldn’t lose sight of what the students had achieved already. First, the faculty inspected steward Jonathan Hastings’s supply of butter and rejected most of it. The tutors had already complained the President Edward Holyoke about the butter, but nobody made any changes. The protest got that very real problem fixed.

Second, the bulk of the student body had stood united from 24 September to 11 October—more than two weeks. They presented a strong defense for their actions, demonstrated unity and order, and commanded the attention of the college’s highest board. Despite all signing that confession, they received no punishment. There were just too many of them.

The students thus achieved a concrete benefit in exchange for a symbolic concession.

What about the individual scholars?

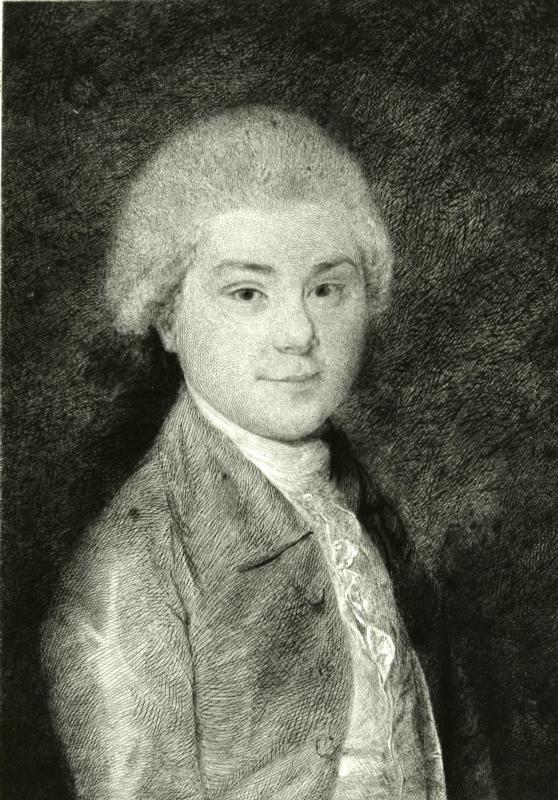

Asa Dunbar was the senior who started the controversy by complaining about the butter to his tutor and refusing the man’s order to sit down. His classmates feared he would be expelled. Instead, the faculty demoted him to the bottom of his class (which was still ranked by social standing rather than grades). Everyone knew that punishment could be reversed, and indeed that’s what the college administration did at the end of the school year.

Earlier I mentioned “a telling of the event that’s entirely in mock Biblical language.” That document refers to Dunbar as “Asa, the scribe,” and his private notebooks show he wrote similar pieces about other events in his life, so Harvard chronicler Clifford K. Shipton concluded he wrote the account. A person doesn’t normally compose and share long, satirical stories about events that embarrass them, so I don’t think Asa Dunbar felt much shame about his actions or punishment.

Thomas Hodgson moderated the first student meeting, which concluded with a mass threat to withdraw from college if Dunbar was expelled. He didn’t graduate with the class of 1767—but that was because in the spring he was caught with a “lewd Woman” in his room. He went home to North Carolina and died young.

Daniel Johnson, the senior who defied the faculty’s demands in long discussions on 26 September, suffered no immediate consequences from this protest at all. He was caught up in the “lewd Woman” infraction with Hodgson and demoted, but then restored to his place again.

After graduating, Dunbar was a minister in Bedford and Salem, and then an attorney in Keene, New Hampshire. One of his grandchildren was Henry David Thoreau, who created his own history of protest.

Johnson became the minister in the town of Harvard. He was a strong supporter of the Revolution, even joining his parishioners in marching toward Boston in April 1775. In the summer of 1777 he served as chaplain for a militia regiment guarding Boston harbor, apparently contracted an illness, and went home and died at the age of thirty.

As for younger Harvard students involved in the butter protest, one of the “College Committee” that signed the defense was Stephen Peabody. He learned his lessons so well that he was in the thick of an even bigger protest in 1768.

Because the administration hadn’t quashed student protest at all.