Col. Gridley’s Half-Pay

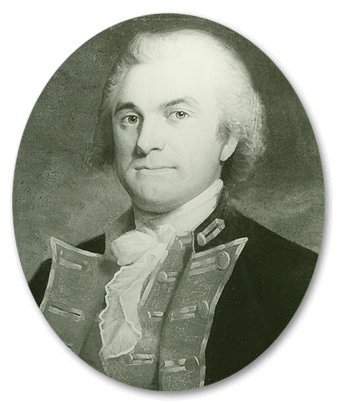

In the same period Scar Gridley’s father, Col. Richard Gridley, was also seeking more pay.

Though promoted to the post of the Continental Army’s Chief Engineer in fall 1775, Col. Gridley had stayed behind in New England at the end of the siege of Boston. And Gen. George Washington was fine with that. He had lost respect for the colonel and preferred his new artillery commander, Henry Knox. Gridley finally retired at the end of 1780.

Back in April 1775, when Col. Gridley agreed to come out of retirement to work for the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, he asked that rebellious legislature to make up for the likely loss of his half-pay pension from the Crown. Once he retired again, the colonel expected that the Continental Congress would start paying the equivalent of that pension since it had taken charge of the army raised in Massachusetts.

In February 1781 the Congress “recommended to the State of Massachusetts to make up to Richard Gridley the depreciation of his pay as engineer at sixty dollars per month…and charge the same to the United States.” It promised to pay the colonel “four hundred and forty-four dollars and two-fifths of a dollar per annum” as a pension. Samuel Huntington transmitted that news to Massachusetts governor John Hancock.

Two years later, however, Gridley reported to Robert Morris “that upon his application to the said State they granted and paid the depreciation by giving their notes, and also made him a grant for the sum of £182 10/ Massachusetts currency, being for eighteen months half pay; and that he had received a warrant on the Treasurer of the State for the said sum, but that he had not received any money upon it.” Gridley had received only government notes, which were rapidly losing their value.

At that time, lots of other retired officers were complaining about their pay as well. Legislators had made more explicit promises to Col. Gridley than the rest, “as he abandoned his British half pay on an agreement made by Congress to indemnify him therefor.” The Congress recognized that difference. But basically they couldn’t do much about it.

TOMORROW: Beating a dead horse.