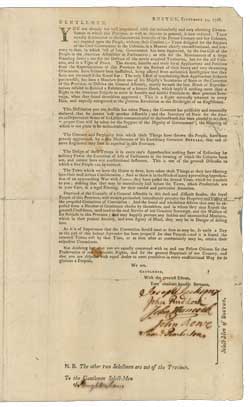

“Boston Surrounded with aboute 14 Ships”

At 3 O’Clock P. M. the Lanceston of 40 Guns, the Mermaid of 28, Glasgow of 20, Keven [Beaver, wrote John Rowe] of 14, Senegal 14, Bonnetta 10, several armed schooners, which with the Romney of 50 Guns (which had been hear most of the Summer) & the other Ships of War before in the Harbour, Capt. [James] Smith in the Mermaid Comadore, all came up to town bringing with them the 14th Regiment Col. [William] Dalrymple & 29th Regt. Col. [Maurice] Care.Boston’s selectmen had been expecting those troops as far back as 10 September. After that, they met on the 11th, 12th, 13th (twice), 14th (twice), and 15th (twice). Most of those meetings produced no official decisions, the exceptions being typical small tasks such as admitting a person to the poorhouse or setting the price of rye bread.

So that now we See Boston Surrounded with aboute 14 Ships, or Vessells of war. The greatest perade perhaps ever seen in the Harbour of Boston.

On the 18th, the selectmen went to the Council Chamber in the Town House and received official word that four regiments were on their way, two from Halifax and two later from Ireland. Those thousands of soldiers would need a place to stay, the Council relayed. Three days later, the selectmen returned to the Council and said the only place for the soldiers was in Castle William.

The selectmen met again on the afternoon of the 21st, the 23rd, 26th, 28th, 29th, and 30th (twice). Again, most of those meetings officially resulted in nothing. The record of the afternoon meeting on the 30th even says: “A number of His Majestys Justices were present, but nothing transacted, matter of minuting.”

(On 26 September a cloth dyer named Thomas Mewse alerted the selectmen that he had come to Boston from Norwich, England, with his son. Mewse would go into “the Weaving Business” with William Molineux, a partnership that broke down in mutual recriminations, lawsuits, and newspaper essays. I wrote a long chapter about how that dispute connects to Molineux’s sudden death in October 1774 for The Road to Concord, and then I cut it for length. But it was nice to see Mewse make his entrance.)

The reason for the selectmen’s frequent meetings, and the magistrates’ presence on the 30th, is that Gov. Francis Bernard was trying to make the Manufactory building near the Common available as barracks. He told Col. Dalrymple that the Manufactory “is a building belonging to the Province and at present not leased or appropriated to any Person or Purpose.”

In fact, there were a few families in that large building weaving cloth or stockings or making buttons on a small scale. Moving them out would require a legal eviction, hence the justices of the peace—but most of those appointees stood with the selectmen in opposing the troops’ presence in town.

As much as Gov. Bernard wanted to turn the Manufactory over to the army, he didn’t want to take all the responsibility for doing so. He had spent almost two weeks trying to get his Council to agree with the idea. Those elected officials refused, also siding with the Boston selectmen.

In his letter to Col. Dalrymple, the governor wrote, “you have requested of me the Use of the building called the manufactory house.” So far as I know, Dalrymple had never been in Boston, but the governor wanted the request to come from the army.

On 30 September, Gov. Bernard finally bit the bullet and acted on his own authority—but he turned all the hard work over to Dalrymple:

as it is my Duty to preserve the Peace of the Town by all means in my Power, for which it is necessary to prevent an intermixture of the Soldiers and the People, as it must certainly give frequent occasions for the breaking the Peace, I do hereby assign & appoint the Manufactory house being a building appropriated to no use, & belonging to the Province; & I do authorise you to take possession of the same as & for a Barrack for the quartering the King’s Troops.Until that building was available, the governor said, he had no objection to the regiments camping on Boston Common. As for straw for that camp, he would speak with the Council—the same uncooperative Council that didn’t want the troops in Boston in the first place.

TOMORROW: The landing.

(The picture above, courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, is one version of Christian Remick’s painting of the fleet in Boston harbor as seen from Long Wharf.)