For more than a century the

U.S. Supreme Court had a seat reserved for New Englanders.

The early Presidents had two good reasons for that. First, by appointing justices equally from all regions of the country those Presidents—especially all those Virginians—avoided charges of favoring their home region.

Second, in its early years the Supreme Court justices also rode circuit, hearing federal cases in their districts. So a New Englander covering the northeastern states wasn’t so far away from home.

For the first two decades, that New Englander was

William Cushing, formerly chief justice in Massachusetts. In 1795 President

George Washington promoted him to be the chief justice, and the Senate confirmed him. But Cushing declined the commission. Being chief justice just wasn’t as prestigious and powerful as the job has become.

Justice Cushing remained on the bench longer than any of the other original court. He was also the last to wear the full judicial

wig inherited from the British system. When Cushing died in 1810, President

James Madison needed a replacement from New England. He also wanted someone from his own Republican party. Which was difficult because most New England lawyers were Federalists.

Madison’s first choice was

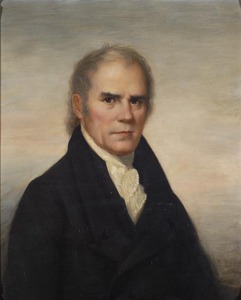

Levi Lincoln of

Hingham—former U.S. attorney general under Thomas Jefferson, former lieutenant and acting governor of Massachusetts (shown above). The Senate voted its approval. But Lincoln declined, citing bad eyes. Again, being a Supreme Court justice wasn’t that great.

Madison then nominated

Alexander Wolcott of

Connecticut, mentioned in

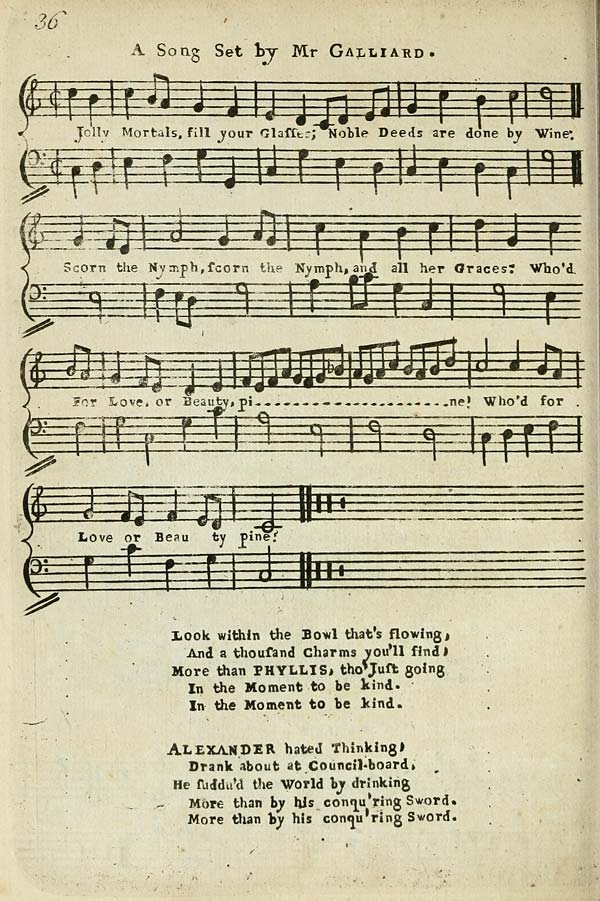

yesterday’s posting. Wolcott had practiced law, but he was primarily known as the leader of his state’s Republicans. He engaged in harsh political disputes and oversaw patronage appointments. The closest he’d gotten to judicial experience was in his own patronage position as a

Customs inspector. The Federalist

Columbian Centinel called Wolcott’s nomination “abominable.”

Nonetheless, the Republicans were firmly in charge of the U.S. Senate, 28 votes to 6, and Supreme Court nominees usually got approved within a week. In Wolcott’s case, the Senators referred the court nomination to a committee for the first time. Then they didn’t take a vote until nine whole days later, on 14 Feb 1811.

The U.S. Senate rejected Alexander Wolcott’s nomination to the Supreme Court by a vote of 24 to 9. This was the largest percentage against any court nominee ever. Even Republican Senators voted against the nomination by a margin of at least 2:1.

Wolcott went back to Connecticut politics. President Madison looked around for another New Englander to nominate to the high Court. Again, he needed a prominent Republican—but one with a less partisan history.

Madison’s third choice was

John Quincy Adams, former Federalist Senator from Massachusetts. Adams had bucked his party’s foreign policy on several issues under President

Thomas Jefferson and ended up a politician without party backing. In 1809 Madison appointed him the

U.S. minister to Russia, a country Adams had first visited as a teen-aged secretary for the

Continental Congress’s envoy,

Francis Dana.

As with Lincoln, the Senate gave their advice and consent in favor of President Madison’s nominee. And as with Lincoln, the nominee declined the job. Adams would go on to be U.S. Secretary of State, President, and a long-time Representative from Massachusetts.

Once again President Madison scanned the New England legal landscape. The best candidate he could find was a lawyer from

Marblehead, only thirty-two years old, with one term in the U.S. House of Representatives under his belt. This was

Joseph Story, still the youngest person ever nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Story was confirmed and served thirty-three years. As an associate justice, law professor, and author, he exercised more influence over the U.S. legal system than anyone else in the early 1800s but Chief Justice

John Marshall.

When Story died in 1845, President James K. Polk nominated Levi Woodbury of

New Hampshire to succeed him. After Woodbury, the justices in that line were Benjamin Curtis of

Watertown; Nathan Clifford of

Maine; Horace Gray of Boston; and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., of Boston. The replacement for Holmes was Benjamin Cardozo of

New York, though by that time Louis Brandeis—a native of Kentucky who had established his legal career in Boston—was representing New England on the high bench.