The Aspect of the Declaration of Independence that Bothers Me

For decades, something about the grievances in the Declaration of Independence has bothered me: They’re not grammatically parallel.

I know this problem might not look as weighty as one-sided descriptions of policy, piling all the blame onto King George, the hypocrisy of complaining about wartime measures the Continental governments had also taken, or the hollowness of those “self-evident” truths in practice, but it really did bother me.

The Continental Congress listed twenty-seven grievances, starting with “He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good” and ending with “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

As you see, the grumbling moves from a vague disagreement about policy and governance to incendiary language about non-white warriors killing women and children.

Along the way, the grammatical structure of those grievances changes. The first thirteen are complete sentences beginning “He has…” Then come “For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us” and eight more similarly constructed phrases that are not even complete sentences. The list resumes the “He has…” for the last five complaints.

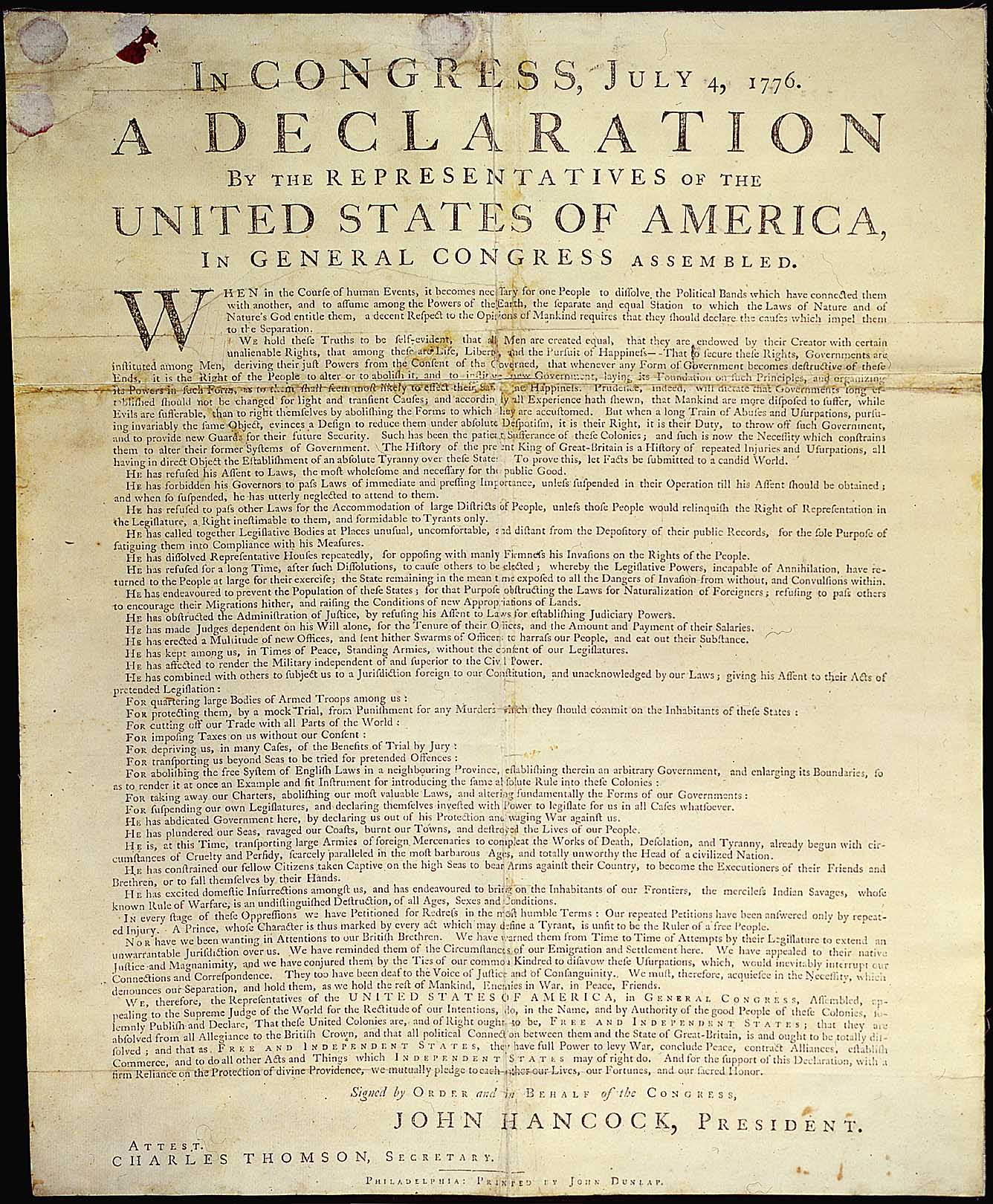

The first printing of the Declaration by John Dunlap, the first newspaper printing, and the official government transcript all format those grievances with the same indentation and emphasis.

The famous handwritten copy likewise makes no clear distinction among the grievances. That’s because none of those clauses are set out in separate paragraphs, scribe Timothy Matlack formatting the whole thing in just two blocks of text.

So if all those complaints are supposed to be parallel, why aren’t they worded in the same way?

Last month in a series of Twitter postings starting here, Jack Rakove, emeritus William Robertson Coe Professor of History and American Studies and professor of political science at Stanford, wrote:

I wondered if those three categories mapped onto the three grammatically distinct groups of complaints. In the end, I concluded they don’t match up exactly, but Rakove’s observation got me thinking about how those groupings pointed in somewhat different directions rather than running in parallel.

TOMORROW: Sorting out the lists.

I know this problem might not look as weighty as one-sided descriptions of policy, piling all the blame onto King George, the hypocrisy of complaining about wartime measures the Continental governments had also taken, or the hollowness of those “self-evident” truths in practice, but it really did bother me.

The Continental Congress listed twenty-seven grievances, starting with “He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good” and ending with “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

As you see, the grumbling moves from a vague disagreement about policy and governance to incendiary language about non-white warriors killing women and children.

Along the way, the grammatical structure of those grievances changes. The first thirteen are complete sentences beginning “He has…” Then come “For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us” and eight more similarly constructed phrases that are not even complete sentences. The list resumes the “He has…” for the last five complaints.

The first printing of the Declaration by John Dunlap, the first newspaper printing, and the official government transcript all format those grievances with the same indentation and emphasis.

The famous handwritten copy likewise makes no clear distinction among the grievances. That’s because none of those clauses are set out in separate paragraphs, scribe Timothy Matlack formatting the whole thing in just two blocks of text.

So if all those complaints are supposed to be parallel, why aren’t they worded in the same way?

Last month in a series of Twitter postings starting here, Jack Rakove, emeritus William Robertson Coe Professor of History and American Studies and professor of political science at Stanford, wrote:

The real structure of the DoI, once past its Preamble, has three distinct parts: a summary of longstanding grievances of imperial governance; a denunciation of all the recent acts adopted in response to the Boston Tea Party and other acts of intercolonial resistance; and a concluding set (I would say the last 5 listed) relating to the forms of military repression and violence directed against the colonists, obviously including but hardly limited to the invitation to insurrection on the part of the enslaved and indigenous peoples.In other words, the first batch of grievances covered the years 1760 to 1773, the next batch the Coercive Acts of 1774, and the last bunch the British government’s decisions since the start of the war.

I wondered if those three categories mapped onto the three grammatically distinct groups of complaints. In the end, I concluded they don’t match up exactly, but Rakove’s observation got me thinking about how those groupings pointed in somewhat different directions rather than running in parallel.

TOMORROW: Sorting out the lists.

1 comment:

I started to smile just reading that you were bothered by the lack of parallel structure in the wording of grievances in the Declaration. I can't wait to follow you to the bottom of this.

Post a Comment