“Voted to proceed to the Business of the Meeting”

In response, those men “unanimously voted to proceed to the Business of the Meeting.” Sheriff Stephen Greenleaf asked moderator William Phillips for a written message to take back to the governor. The meeting came up with this note, addressed to the sheriff:

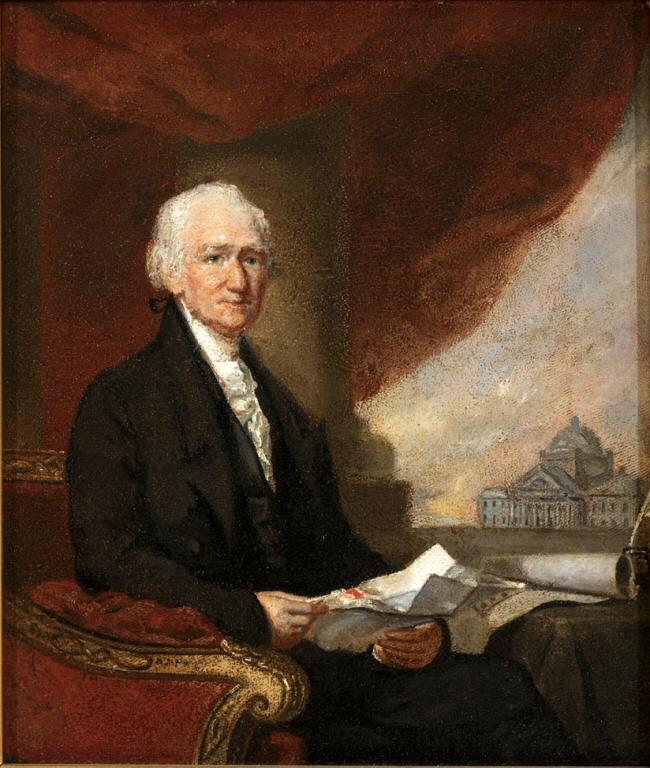

It is the unanimous Desire of this Body, that you inform his Honor the Lieutenant-Governor, that his Address to this Body has been read and attended to, with all that Deference and Solemnity which the Message and the Times demand; and it is the unanimous Opinion of this Body, after serious Consideration and Debate, that this Meeting is warranted by Law: And they desire you to inform his Honor, that they had determined to keep Consciences void of just Offence towards God and towards Man.In Smugglers and Patriots, John W. Tyler stated that letter was written in the fine hand of John Hancock (shown above). The previous week, he shied from leading a crowd to the governor’s house. Now Hancock was ready to stand at the front of the movement.

Before leaving, Greenleaf made sure to tell the people he wanted “to be considered in the Light only of the Bearer of his Honor’s Letter.” In other words, Hutchinson stood alone, his show of authority ending in a resounding defeat.

The “Body of the Trade” then proceeded through a series of votes. In response to accusations that someone had tried to burn down the store of importer William Jackson, the meeting offered a £100 reward for the arsonist. A further resolution suggested that an enemy of the community—Harbottle Dorr suggested it was Jackson himself—had planted the evidence of that crime.

Another resolution asked people “totally to abstain from the use of Tea upon any pretence whatever” since tea accounted for “the greatest Part of the Revenue” from the Townshend duties.

But the main business of the meeting was about naming and shaming the shopkeepers who were still defying the non-importation committee.

The first group was the merchants Jackson, Theophilus Lillie, John Taylor, and Nathaniel Rogers. The meeting deemed them “obstinate and inveterate Enemies of their Country, and Subverters of the Rights and Liberties of this Continent.” It declared that people should respond by “withholding not only all commercial Dealing; but every Act and Office of common Civility” from them. The resolution went on for a long time. You can read it here in the Boston Gazette.

Then the meeting turned to a second group of defiant businesspeople:

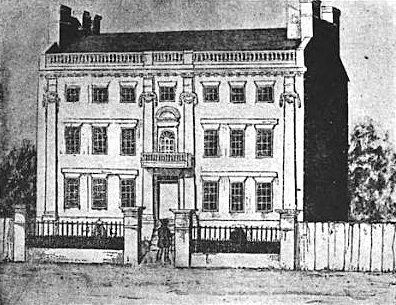

- John Bernard, a grown son of the departed governor, Francis Bernard.

- James and Patrick McMaster, brothers from Scotland who had set up as “factors,” or wholesalers, in Boston.

- Ame and Elizabeth Cumings, sisters from Concord who had opened a shop to support themselves; their late parents had also come from Scotland.

- John Mein, printer from Scotland, still in hiding at Castle William after a fight with merchants back in October.

The next day, Lt. Gov. Hutchinson wrote to Lord Hillsborough, the Secretary of State, about his attempt to stop the meeting. He said he’d spoken with Phillips, his Council, and the town’s justices of the peace about how such meetings would lead to “high treason,” but no one had agreed with him. He acknowledged his letter had failed to disperse the crowd. But Hutchinson insisted that “it made them more anxious to restrain all disorders.”

In the coming weeks, we’ll see how that worked out.