“The notion of Vampyres” in Early America

The 1784 Connecticut Courant report about Isaac Johnson having the bodies of his children dug up, hoping to save other members of his family from consumption, didn’t use the word “vampire.”

Two years before, the Connecticut poet John Trumbull had used that word in the fourth canto of M’Fingal while discussing British prison commissary Joshua Loring:

The word “vampire” appeared more often in American newspapers during the following decades. One source was European literature. In 1786, for example, the French author Louis-Sébastien Mercier published a collection titled Mon Bonnet de nuit, soon translated into English as The Nightcap.

On 24 Nov 1787 the Pennsylvania Evening-Post published one piece by Mercier called “Opulence: A Vision.” Its narrator described obtaining the philosopher’s stone, which leads to wealth and a pretty young wife. Then, when everything seems to be going well—

American newspapers also printed extracts from Dr. Erasmus Darwin’s Botanic Garden (composed 1789-1793), which made a poetic hero of Benjamin Franklin and included such lines as this:

In fact, one of the earliest uses of ”vampires” as a political metaphor in English had a link to the American Revolution. It appeared during debate over how Parliament should respond to the Boston Tea Party in April 1774, as reported in London newspapers and eventually the 9 June 1774 Massachusetts Spy:

Of course, poets and propagandists could write about vampires without believing that they actually existed. And New England farmers didn’t need to know the word “vampire” to hold out hope that digging up bodies and burning those that seemed too well preserved might cure the dying. But as the word became more common in the 1800s, the belief might have spread along with it.

Two years before, the Connecticut poet John Trumbull had used that word in the fourth canto of M’Fingal while discussing British prison commissary Joshua Loring:

Aloft the mighty Loring stood,But Trumbull also included a footnoted explanation for his readers:

And thriv’d like Vampyre on their blood.

The notion of Vampyres is a superstition, that has greatly prevailed in many parts of Europe. They pretend it is a dead body, which rises out of its grave in the night, and sucks the blood of the living.Clearly the concept of vampires wasn’t yet common knowledge for Americans, even those who read satirical poetry.

The word “vampire” appeared more often in American newspapers during the following decades. One source was European literature. In 1786, for example, the French author Louis-Sébastien Mercier published a collection titled Mon Bonnet de nuit, soon translated into English as The Nightcap.

On 24 Nov 1787 the Pennsylvania Evening-Post published one piece by Mercier called “Opulence: A Vision.” Its narrator described obtaining the philosopher’s stone, which leads to wealth and a pretty young wife. Then, when everything seems to be going well—

a crowd of Vampires entered the room, and began to unfurnish my apartment. In vain did I make signs to them to desist; they carried every thing away, making many low bows. . . .(Spoiler: It was all a dream.)

Then I turned to my dearly beloved, and, in the effusion of my soul, said to her, “The Vampires have stripped me of all I had; but still I have thee.” She wept—I thought it proceeded from tenderness; but my wife so mild, so open, sprang from my arms, ran over the apartment with the looks and gesture of a fury, and, seeing it was stript, seized on a purse the Vampires had forgot in one of my waistcoat pockets, came to me, and, applying a vigorous stroke to my cheek, disappeared.

Stunned with this scene, I got up in bed, in order to run after my wife, for I loved her. I had grown fat from living well; but a little Vampire, thinner still than the others, sprang upon me, and began to suck me alive. He swelled on my body as I grew lank; he dried me up from head to foot, gorging himself with my blood, and I became so light, that the wind carried me off my magnificent bed with rich curtains through the window.

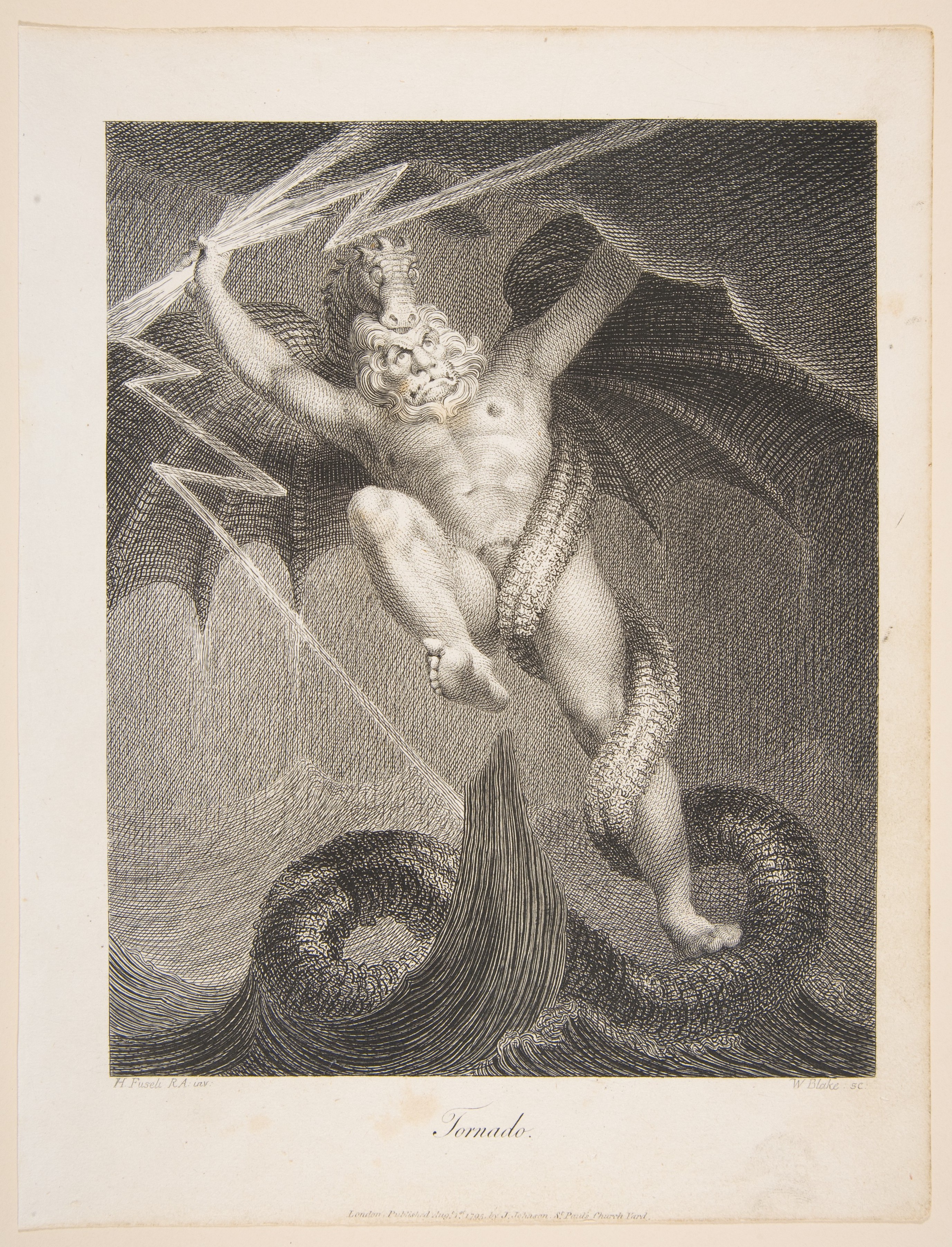

American newspapers also printed extracts from Dr. Erasmus Darwin’s Botanic Garden (composed 1789-1793), which made a poetic hero of Benjamin Franklin and included such lines as this:

So, born on sounding pinions to the West,Darwin used vampires, sucking blood from innocents, as a political metaphor. American authors couldn’t resist doing the same:

When Tyrant-Power had built his eagle nest;

While from his eyry shriek’d the famish’d brood,

Clenched their sharp claws, and champ’d their beaks for blood,

Immortal FRANKLIN watch’d the callow crew,

And stabb’d the struggling Vampires, ere they flew.

- Joel Barlow: “Courts and Kings, / These are the vampires nurs’d on nature’s spoils” (Gazette of the United States, 14 July 1792)

- “The Versifier”: “You’ll foil that Treasury Vampire who from spite, / Sucks from our coin its blood night after night” (Connecticut Courant, 4 Feb 1793)

In fact, one of the earliest uses of ”vampires” as a political metaphor in English had a link to the American Revolution. It appeared during debate over how Parliament should respond to the Boston Tea Party in April 1774, as reported in London newspapers and eventually the 9 June 1774 Massachusetts Spy:

Mr. [Edmund] Burke rose to explain, that he did not mean to cast the least slur upon the character of Mr. [George] Grenville; and concluded with saying, he would not raise the bodies of the dead, to make them vampires to suck out the virtues of the living.That line isn’t as well remembered as the two-hour speech Burke had given earlier that day, usually titled “On American Taxation.” But it shows how the idea of vampires had penetrated British culture on its way to America.

Of course, poets and propagandists could write about vampires without believing that they actually existed. And New England farmers didn’t need to know the word “vampire” to hold out hope that digging up bodies and burning those that seemed too well preserved might cure the dying. But as the word became more common in the 1800s, the belief might have spread along with it.

No comments:

Post a Comment