An “Extraordinary Proposal” from Lt. Gov. Hutchinson

The political prospects of non-importation veered wildly back and forth in the middle of January 1770.

As I’ve been tracing, the month opened with the town’s initial public agreement not to import goods from Britain expiring, a few shopkeepers openly defying the boycott, and some wealthy merchants decidedly lukewarm on it.

Of the top merchants on the original non-importation committee, rumors said that John Hancock and John Barrett had become “cool in the cause.” Thomas Cushing and Edward Payne had “deserted” it. John Rowe had trimmed his sails so much he was dining with Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson.

To regain control, the town’s political organizers called a big public meeting, taking the movement away from the merchants and bringing in the wider public. In a show of popular support, hundreds of men massed outside one of the importers’ shops. At the end of 17 January, the acting governor’s sons, Thomas Hutchinson, Jr., and Elisha Hutchinson, told representatives of the meeting that they were once again willing to cooperate.

Just one day later, however, the Hutchinsons were back to being defiant. Their father told the crowd in the king’s name to disperse from outside his house. The people then visited six other importers, but they all refused to yield their goods. That evening, supporters of the royal government thought the boycott would soon fall apart.

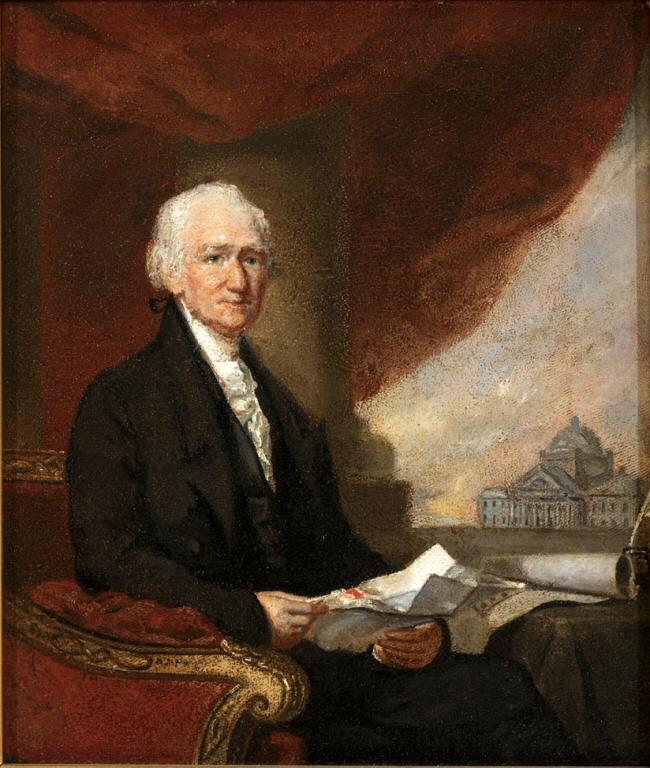

But then the acting governor shifted his stance. On the morning of 19 January, according to a Crown informant, Hutchinson sent for William Phillips, the moderator of those public meetings (shown above), and a member of the merchants’ inspection committee. He “told them that upon consideration he was now ready to make his Sons deliver up to the Committee what they had in their store and the Cash for the part they had sold.”

The Crown source, who appears to have been reporting to Customs Collector Joseph Harrison, called the acting governor’s change an “extraordinary proposal,” a “sudden and unexpected step” that “struck every person with astonishment.” According to that observer:

Bernard Bailyn’s Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson says nothing about this moment, which would soon be overshadowed by many other events of 1770. The best analysis seems to be in John W. Tyler’s Smugglers and Patriots.

It looks to me like Lt. Gov. Hutchinson felt that honor required his sons to cooperate with the non-importation committee for two reasons. First, Thomas, Jr., and Elisha had reached some sort of agreement on 17 January to turn over their tea. Their father reviewed the notes of that discussion. I suspect he felt that the young men were now duty-bound to stick to those terms.

Second, the acting governor knew he was vulnerable to charges of conflict of interest. If he took any steps to support the town’s importers, the Whigs could complain he was abusing his office to benefit his sons. Indeed, Hutchinson had invested a large chunk of money in his sons’ business. By taking Thomas, Jr., and Elisha out of the dispute, Lt. Gov. Hutchinson later explained, he had more leeway to protect the remaining importers.

Of course, the immediate effect the Hutchinsons’ cave-in was that the other importers got nervous. They saw the acting governor and his well-connected sons yielding to the Whigs. It was all very well for Lt. Gov. Hutchinson to say he would support them more strongly now—but would he really? Meanwhile, the “Body of the Trade” in Faneuil Hall continued to grow, amounting to “more than Twelve Hundred Persons” on 19 January, according to the Boston Gazette.

That morning, Nathaniel Cary sent the public meeting a letter to say he was turning over his imported goods to the committee. Late in the day Benjamin Greene followed suit. Deacon Phillips had moved quickly to take the Hutchinsons’ tea inventory. That left only four importers still in defiance: William Jackson, Theophilus Lillie, John Taylor, and Nathaniel Rogers.

The “Body of the People” and their leaders recognized victory. They quickly accepted those merchants’ offers and adjourned the meeting until Tuesday.

COMING UP: The battle rejoined.

As I’ve been tracing, the month opened with the town’s initial public agreement not to import goods from Britain expiring, a few shopkeepers openly defying the boycott, and some wealthy merchants decidedly lukewarm on it.

Of the top merchants on the original non-importation committee, rumors said that John Hancock and John Barrett had become “cool in the cause.” Thomas Cushing and Edward Payne had “deserted” it. John Rowe had trimmed his sails so much he was dining with Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson.

To regain control, the town’s political organizers called a big public meeting, taking the movement away from the merchants and bringing in the wider public. In a show of popular support, hundreds of men massed outside one of the importers’ shops. At the end of 17 January, the acting governor’s sons, Thomas Hutchinson, Jr., and Elisha Hutchinson, told representatives of the meeting that they were once again willing to cooperate.

Just one day later, however, the Hutchinsons were back to being defiant. Their father told the crowd in the king’s name to disperse from outside his house. The people then visited six other importers, but they all refused to yield their goods. That evening, supporters of the royal government thought the boycott would soon fall apart.

But then the acting governor shifted his stance. On the morning of 19 January, according to a Crown informant, Hutchinson sent for William Phillips, the moderator of those public meetings (shown above), and a member of the merchants’ inspection committee. He “told them that upon consideration he was now ready to make his Sons deliver up to the Committee what they had in their store and the Cash for the part they had sold.”

The Crown source, who appears to have been reporting to Customs Collector Joseph Harrison, called the acting governor’s change an “extraordinary proposal,” a “sudden and unexpected step” that “struck every person with astonishment.” According to that observer:

it was well known that the most zealous partizans of the faction had given up all hopes of carrying their point the Night before, and that their only intention of meeting this day was to pass a few resolves to publish in the Newspapers as a justification of their Conduct to the other Collonies.The informant might overstate how little hope the top Whigs had felt, but the governor’s cooperation was still an overnight reversal.

Bernard Bailyn’s Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson says nothing about this moment, which would soon be overshadowed by many other events of 1770. The best analysis seems to be in John W. Tyler’s Smugglers and Patriots.

It looks to me like Lt. Gov. Hutchinson felt that honor required his sons to cooperate with the non-importation committee for two reasons. First, Thomas, Jr., and Elisha had reached some sort of agreement on 17 January to turn over their tea. Their father reviewed the notes of that discussion. I suspect he felt that the young men were now duty-bound to stick to those terms.

Second, the acting governor knew he was vulnerable to charges of conflict of interest. If he took any steps to support the town’s importers, the Whigs could complain he was abusing his office to benefit his sons. Indeed, Hutchinson had invested a large chunk of money in his sons’ business. By taking Thomas, Jr., and Elisha out of the dispute, Lt. Gov. Hutchinson later explained, he had more leeway to protect the remaining importers.

Of course, the immediate effect the Hutchinsons’ cave-in was that the other importers got nervous. They saw the acting governor and his well-connected sons yielding to the Whigs. It was all very well for Lt. Gov. Hutchinson to say he would support them more strongly now—but would he really? Meanwhile, the “Body of the Trade” in Faneuil Hall continued to grow, amounting to “more than Twelve Hundred Persons” on 19 January, according to the Boston Gazette.

That morning, Nathaniel Cary sent the public meeting a letter to say he was turning over his imported goods to the committee. Late in the day Benjamin Greene followed suit. Deacon Phillips had moved quickly to take the Hutchinsons’ tea inventory. That left only four importers still in defiance: William Jackson, Theophilus Lillie, John Taylor, and Nathaniel Rogers.

The “Body of the People” and their leaders recognized victory. They quickly accepted those merchants’ offers and adjourned the meeting until Tuesday.

COMING UP: The battle rejoined.

No comments:

Post a Comment