When Did the American Revolution Begin?

Is this the anniversary of the day the American Revolution began?

That of course depends on accepting the idea that the American Revolution started on an identifiable day instead of building up gradually. Some revolutions are seen to start with a bang, like the storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, and others aren’t.

If there was one day when the political tensions between the imperial government in London and the North American colonies turned into (as yet unrecognized) revolution, I argue that day was 14 Aug 1765.

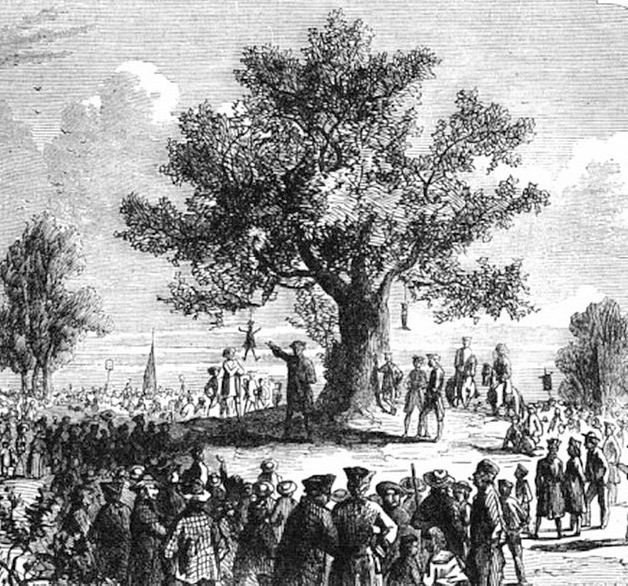

That’s when Boston’s Loyall Nine took American dissatisfaction with Parliament’s new Stamp Act out from legislative chambers, courtrooms, and newspaper essays into the streets. Specifically, into the main street through Boston where it met Essex Street in the shadow of a great elm.

In a notebook where he made notes on major historical events, the Rev. James Freeman collected details on the 14 August protest:

Boston had seen public disturbances, including the Knowles Riots in 1747. But this Stamp Act protest was something new. It was action against an official British law, not how particular officials were carrying out a disputed policy. The protest was designed not just to communicate anger to men in authority but also to educate and rile up ordinary people—the demonstrators stopped farmers coming into town and asked if their goods had been properly “stamped.”

Furthermore, Boston’s protests provided the template for more anti-Stamp Act actions up and down the Atlantic coast. Almost all those demonstrations included effigies of royal officials festooned with signs to make sure no one missed the point, bonfires after dark, and some light rioting. That produced a continental movement, not just a local brawl. Eventually that movement and the principles it promulgated, such as “no taxation without representation,” built into the American Revolution.

(I should note that James Freeman’s account must have been digested from newspapers and older people’s memories. In 1765 Freeman was only six years old and living in Charlestown.)

That of course depends on accepting the idea that the American Revolution started on an identifiable day instead of building up gradually. Some revolutions are seen to start with a bang, like the storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, and others aren’t.

If there was one day when the political tensions between the imperial government in London and the North American colonies turned into (as yet unrecognized) revolution, I argue that day was 14 Aug 1765.

That’s when Boston’s Loyall Nine took American dissatisfaction with Parliament’s new Stamp Act out from legislative chambers, courtrooms, and newspaper essays into the streets. Specifically, into the main street through Boston where it met Essex Street in the shadow of a great elm.

In a notebook where he made notes on major historical events, the Rev. James Freeman collected details on the 14 August protest:

The effigies of the distributor of stamps [Andrew Oliver], pendant, behind whom hung a boot newly soled with a Grenville sole, out of wc. proceeded the Devil was exhibited on the great tree in main street. The spectacle continued ye whole day wh.out the least opposition.Colonial politicians had gotten into many disputes with London and its appointees, such as the Boston merchants’ lawsuit against Customs officer Charles Paxton’s writs of assistance. But those disagreements went through formal, legal channels. So did the early objections to the Stamp Act. We have to go back to Massachusetts’s uprising against Gov. Edmund Andros in 1689 to find a big extralegal move against the government—and that was of course part of Britain’s Glorious Revolution.

About evening a no. of reputable persons assembled, cut down the effigies, placed it on a [wagon?], and covering it with a sheet, they proceeded in a regular solemn manner, amidst the acclamations of the populace thro the town, till they arrived at ye Court House [Town House], where after a short pause, they pass’d, & proceeding down King’s Street, soon reached a certain edifice then building for ye reception of stamps wc they quickly levelled with ye ground it stood on & wh the wooden remains therefrom march’d to Fort Hill, where kindling a fire the[y] burnt the effigies.

The gentleman who was to have been the distributor of the stamps had his house [?] near the hill, & by that means it received from the populace some small insults, such as breaking the windows of his kitchen which would have ended there, had not some indiscretions been committed by his friends within, wc so enraged the people, that they were not to be restrained from entering the house; the damages however was not great

Boston had seen public disturbances, including the Knowles Riots in 1747. But this Stamp Act protest was something new. It was action against an official British law, not how particular officials were carrying out a disputed policy. The protest was designed not just to communicate anger to men in authority but also to educate and rile up ordinary people—the demonstrators stopped farmers coming into town and asked if their goods had been properly “stamped.”

Furthermore, Boston’s protests provided the template for more anti-Stamp Act actions up and down the Atlantic coast. Almost all those demonstrations included effigies of royal officials festooned with signs to make sure no one missed the point, bonfires after dark, and some light rioting. That produced a continental movement, not just a local brawl. Eventually that movement and the principles it promulgated, such as “no taxation without representation,” built into the American Revolution.

(I should note that James Freeman’s account must have been digested from newspapers and older people’s memories. In 1765 Freeman was only six years old and living in Charlestown.)