“Possibly not the best man to colonize a new country”

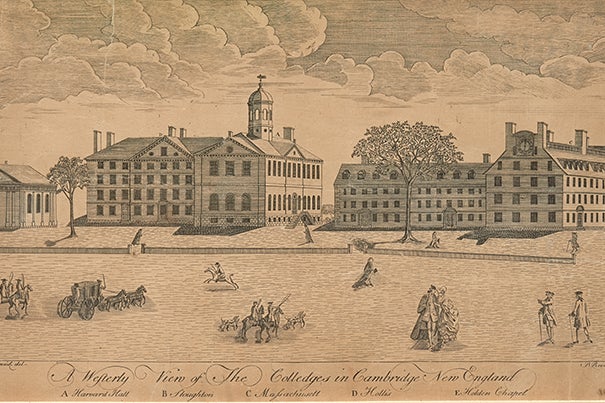

Hastings addressed his correspondent as “Friend Jacob.” Their families were known to each other, and Jacob probably had connections to Harvard College.

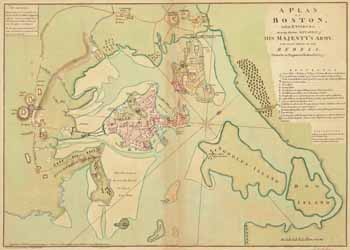

Another clue to Hastings’s correspondent is his comment “Am happy you had so safe a Passage & found your Friends well.” Jacob was obviously traveling. Hastings then offered basic information about the siege, meaning he knew Jacob was far from Massachusetts. Crown forces probably intercepted the letter at sea, not on land.

I looked at the entries in Sibley’s Harvard Graduates for Harvard students in this period named Jacob who might have gone abroad. Almost all were settled down as ministers by 1775, usually inside Massachusetts.

One remaining candidate is Jacob Welsh (1755–1822) from the class of 1774. He was the son of John Welsh (1730–1812), a Boston jeweler and member of the club that used the silver punch bowl now called the “Sons of Liberty Bowl.” This Jacob had one brother, John, Jr., born in 1757.

Sibley’s says nothing about Jacob Welsh’s whereabouts between graduating in July 1774 and entering the Continental Army as an ensign at the start of 1776. (He served until late 1778, first at Fort Ticonderoga and then in the artillery.) Did Welsh leave Massachusetts in that stretch, missing the start of the Revolutionary War because he was in Europe, the Caribbean, or the west?

Jacob Welsh did prove more peripatetic than most of his peers. In addition, Sibley’s says, he “looked for the main chance wherever it might present itself.” After the war he settled in Lunenburg briefly, serving as the town’s legislative representative. But then he sailed to England, smuggling home a “carding and spinning machine” in hopes of securing a state patent for himself. In 1791 Welsh went to Philadelphia and applied to President George Washington to help build the new national capital. He invested in lots of land, as far afield as Louisiana.

In 1807, it appears, Welsh wrote to Gen. Henry Burbeck, a fellow veteran of the Continental artillery corps. According to Heritage Auctions, he submitted “suggestions for the defense of Boston,” including “substitutions for round cannonballs.”

By 1809 Welsh faced a legal judgment of almost a thousand dollars owed to a merchant in Salem. The authorities began to seize his local property. Welsh lit out for Geauga County, Ohio, to manage land that his father had bought a decade before. A county history published in 1878 stated:

Jacob Welsh was a native of Boston, of an old family, and reared in luxury, possibly not the best man to colonize a new country. At the time he came to Ohio, he was a middle-aged man; a gentleman of the old school, of medium height, fair complexion, dressed in small-clothes, with long hose and buckles at the knee, and shoe-buckles over the instep, liberally educated, of imposing appearance and stately address, quite fitted to the aristocratic drawing-rooms of Boston, but not appearing to especial advantage in the woods, trails, and cabins of the Western Reserve. While he was a good conversationalist, he had little energy, small business capacity, and a large disposition to spend money.After another decade, enough people had settled around Welsh’s land to form a township. He promised his neighbors to “give glass and nails for a meeting-house, and fifty acres of land, to settle a minister.” In return, the township was named after him. In April 1820 Welshfield Township had its first election, and Jacob Welsh was chosen to be a trustee.

According to that county history, after Welsh died in 1822 locals found that he had “forgot” his promised bequests. Twelve years later, the community changed its name to Troy Township. That township’s website offers a more compact version of the story while Sibley’s says Welsh did make his promised donation. The county histories from 1878 and 1880 seem best documented, so I’ve relied on them.

Jacob Welsh’s gravestone appears above, courtesy of Find-a-Grave. The central, unincorporated part of Troy Township is still called Welshfield.