“I was requested by my Father to go to the Stable”

As I described yesterday, in 1791 Duncan Ingraham asked the Massachusetts government to compensate him for property taken from him before the Revolutionary War.

Specifically, Ingraham wanted to be paid for “four, four pound iron Cannon of the value ninety six pounds.” (A “four pound” cannon didn’t weigh or cost four pounds; rather, it shot a cannonball that weighed four pounds.)

To support that claim, Ingraham attached an affidavit from dry goods merchant John Molineux (1753-1794) which said:

That October 1774 date is significant. The congress convened for the first time on 7 October. Then delegates debated how best to oppose the royal authorities. Not until 20 October did the shadow legislature formally take up the question of “what is necessary to be now done for the defence and safety of the province,” and it took another week before the body appointed a committee to start buying military supplies.

That means Molineux was collecting cannon—which have no peacetime use—for the Provincial Congress before that legislature officially voted to prepare for war. We know Molineux must have acted before that 27 October vote because he died on 22 October.

Nonetheless, in 1792 the official state legislature paid Duncan Ingraham for his four iron cannon, recognizing that they had become part of the Patriots’ artillery force. Molineux probably jumped the gun, or in fact several guns, but retroactively the government agreed that he’d acted “by Authority.”

TOMORROW: How much money did Ingraham get?

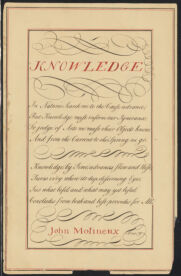

(The image above is a handwriting specimen that John Molineux produced in the 1760s for his writing-school master, Abiah Holbrook, now in the Harvard University library collection.)

Specifically, Ingraham wanted to be paid for “four, four pound iron Cannon of the value ninety six pounds.” (A “four pound” cannon didn’t weigh or cost four pounds; rather, it shot a cannonball that weighed four pounds.)

To support that claim, Ingraham attached an affidavit from dry goods merchant John Molineux (1753-1794) which said:

I John Molineux of Boston in the County of Suffolk & Commonwealth of Massachusetts, declare, that according to the best of my remembrance, some time in the Month of October in the Year 1774, I was requested by my Father to go to the Stable, belonging to the House of Capt. Ingraham at West Boston, with two Teams, & take from thence two Pair Cannon, which was accordingly done, & conveyed into the Country, & beleive they were taken by AuthorityMolineux’s father was the hardware merchant William Molineux, who had been at the forefront of the Boston resistance, pushing into confrontations, since about 1767. Ingraham was thus the second Boston businessman, after Joseph Webb, to formally claim that William Molineux had taken cannon from him for the use of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress.

That October 1774 date is significant. The congress convened for the first time on 7 October. Then delegates debated how best to oppose the royal authorities. Not until 20 October did the shadow legislature formally take up the question of “what is necessary to be now done for the defence and safety of the province,” and it took another week before the body appointed a committee to start buying military supplies.

That means Molineux was collecting cannon—which have no peacetime use—for the Provincial Congress before that legislature officially voted to prepare for war. We know Molineux must have acted before that 27 October vote because he died on 22 October.

Nonetheless, in 1792 the official state legislature paid Duncan Ingraham for his four iron cannon, recognizing that they had become part of the Patriots’ artillery force. Molineux probably jumped the gun, or in fact several guns, but retroactively the government agreed that he’d acted “by Authority.”

TOMORROW: How much money did Ingraham get?

(The image above is a handwriting specimen that John Molineux produced in the 1760s for his writing-school master, Abiah Holbrook, now in the Harvard University library collection.)