“I then went up stairs into the lower west chamber”

Though one of the most respected magistrates in Boston refused to proceed with that case, the grand jury decided to investigate. According to an anonymous Crown informant:

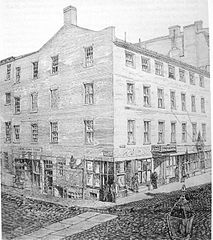

the Grand Jury had the people who were in the Custom House, Vizt. [Bartholomew] Green’s Son [Hammond] & Daughter [Ann], and Thomas [Greenwood] & Molly [Rogers] two Servants, before them, once and sometimes twice a day for several days, but they continued uniform in one story Vizt. that there was no other person in the house that Night but themselves that at the time the soldiers fired, they were in the Room, where the supposed fireing was, and were certain there was no such thing.On 24 Mar 1770, 250 years ago today, Justices John Ruddock and John Hill took down the testimony of three of the people who looked after the Customs House: John Green, his brother Hammond Green, and Thomas Greenwood.

Every method was made use of by threatning to make them fix it on some person but to no effect—

I’ve quoted two of those men in detail before, so here’s what Hammond Green had to say about the evening of 5 March, as printed in the Short Narrative report:

between the hours of eight and nine o’clock, I went to the Custom-house; when I came to the front-door of the said house, there were standing two young women belonging to said house [Elizabeth Avery and Mary Rogers], and two boys belonging to Mr. [John] Piemont the barber [Bartholomew Broaders and Edward Garrick];Jackson had already testified on 16 March that “when I knocked at the Custom-house door, all the persons I saw at the window over the centry box at the Customhouse (which window was then opened) was Mr. Hammond Green and some women.”

I went into the house, and they all followed me, after that Mr. Sawny Irving came into the kitchen where we were, and afterwards I lighted him out at the front-door; I then went back into the kitchen again, and the boys above-mentioned went out; after that two other boys, belonging to Mr. Plemont [one probably Richard Ward], came into the kitchen, also my brother John, who had been in a little while before;

he went to the back door and opened it, saying that something was the matter in the street, upon which, with the other three, I went to the corner of Royal Exchange-lane in King-street, and heard an huzzaing, as I thought, towards Dr. [Samuel] Cooper’s meeting, and then saw one of the first-mentioned boys, who said the centry had struck him; at which time there were not above eight or nine men and boys in King-street;

after that I went to the steps of the custom-house door, and Mary Rogers, Eliza. Avery, and Ann Green, came to the door, at the same time heard a bell ring, upon the people’s crying fire, we all went into the house and I lock’d the door, saying, we shall know if any body comes;

after that, Thomas Greenwood came to the door and I let him in, he said, that there was a number of people in the street; I told him if he wanted to see any thing to go up stairs, but to take no candle with him; he went up stairs, and the three women aforementioned went with him, and I went and fastened the windows, doors, and gate;

I left the light in the kitchen, and was going up stairs, but met Greenwood in the room next to the kitchen, and he said, that he would not stay in the house, for he was afraid it would be pulled down, but I was not afraid of any such thing;

I then went up stairs into the lower west chamber, next to Royal Exchange-lane, and saw several guns fired in King-street, which killed three persons, which I saw lay on the snow in the street, supposing the snow to be near a foot deep;

after that, I let Eliza. Avery out of the front door, and shut it after her, and went up the chamber again;

then my father, Mr. Bartholomew Green, came and knock’d at the door, and I let him in; we both went into the kitchen and he asked me what was the matter; I told him that there were three persons shot by the soldiers who stood at the door of the Customhouse; he then asked me where the girls were, I told him they were up stairs, and we went up together, and he opened the window, and I shut it again directly; he then opened it again, and we both looked out;

at which time Mr. Thomas Jackson, jun. knock’d at the door,

I…asked who was there?

Mr. Jackson said, it is I, Hammond let me in;

I told if him my father was out, or any of the commissioners came, I would not let them in.

In sum, Hammond Green swore that he’d been in the Customs House the whole night, and he hadn’t seen Charles Bourgate, Edward Manwaring, John Munro, or a “tall man” with a musket. Furthermore, five other people in or around the building corroborated Green’s story. Four had even been in the room where the gunmen supposedly stood. And the local authorities had sworn testimony from at least four of those witnesses.

Nevertheless, the legal case against Edward Manwaring rolled on.