“I will take your Body and I will Tar it”

But I couldn’t find that text and had to settle for quoting the proclamation Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson issued about it.

Later I came across the text of that letter in E. Alfred Jones’s The Loyalists of Massachusetts, so I’ll quote it today.

Henry’s wife Christian had already told her friend Elizabeth Smith about the local protesters:

the first thing that fell a Sacrifice to their Mallace and reveng was the Coach which caused so much desention between us they took the cushings out of and put them in the Brook and the next night Cut the Carraig to Peices.I first interpreted that “desention” to be between the Barneses, perhaps arguing over the expense of the coach. But in another letter Christian Barnes told Smith about “the Person that cut your Coach to Peices,” meaning that vehicle had first belonged to Smith or her late husband. So now I’m wondering if there had been some disagreement between the two ladies over that coach—perhaps Smith insisting that the Barneses take it as she left for Britain and Christian Barnes trying to resist.

The anonymous letter referred to the coach as a “booby hut,” a New England term for a carriage or coach body put on sleigh runners, as John Hancock’s coach has been preserved. Was that just a pejorative reference, or had the Smith carriage been left on runners since the winter?

In any event, Henry Barnes’s public complaints about the destruction of that vehicle spurred the anonymous writer:

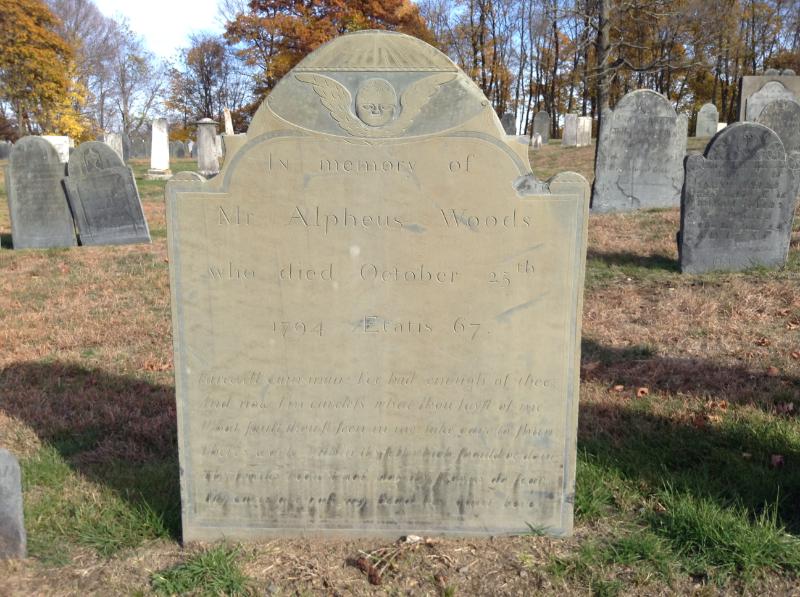

I understand you are about carrying your Old dam’d Booby Hutt to the General Court and from thence Home to England to get recompence for all the damage you have sustained since you have been an infamous Importer or a common Enemy to the Country—I find it striking that this letter doesn’t speak in the voice of the community as Whig missives usually did. Instead, the writer emphasizes himself as an individual—willing to sacrifice for the country, to be sure, but speaking and acting on his own. That makes me inclined to think it didn’t come from Alpheus Woods or another member of the Marlborough town committee to enforce non-importation but from someone riled up by the conflict and perhaps not in his right mind.

Therefore if you only want recompence for the damage you have done the Country in Importing goods contrary to the Agreement of Body of Merchants on this Continent I will recompence you without going there or any where else for I am determined to fetch you to terms even if I do it at the expence of my own Soul, or the Coat of a Sore Back or any other punishment in this World only for the good of my Country, for I stile myself a Son of LIBERTY,

therefore if you will Shut up your Store and Sell nothing out, nor Import any goods till the Importation takes place you shall sustain no more damage

But if not I will Fire your House and Store and destroy all your substance you have on the earth, And I will take your Body and I will Tar it, and if nothing else will do but Death you shall have it certainly, and so you will have no more Notice and if you do it by the 20th June 1770 Good and well, and if not you may depend upon my being as good as my word and so I will never write no more and so I stile myself Inspector General