To discourage various sorts of bad behavior, the town elected twelve men, one from each ward, to the office of “Tything Men.” In his dictionary Samuel Johnson defined a tithingman as “A petty police office; an under-constable.”

The town already had a warden and a constable from each ward, enforcing the Sabbath, delivering writs, and otherwise policing public morals. But in this month they apparently needed help.

Notably, colonial Boston never elected tithingmen again. The town had done without them since 1727. Yet the town felt they were important in 1770—perhaps as a belated response to the presence of soldiers, perhaps because with the Massacre people felt a renewed need for the town to look proper.

The committee on how “to strengthen the Non Importation Agreement; discountenance the Consumption of Tea and for employing the Poor by encouraging Home Manufactures” reported that three new ships would be built in town. Those vessels would of course provide for more employment, but how they affected tea and imports is unclear. Nonetheless, that committee’s report “passed in the affermative by a unanimous Vote.”

Later, another committee reported that 212 sellers of tea had signed an agreement “not to sell any more Teas, till the late Revenue Acts are repealed,” and others were willing to agree “if its general.” Bostonians had no way of knowing that over in London the Parliament was already moving to repeal the Townshend duties—except the one that produced the most revenue, the tax on tea.

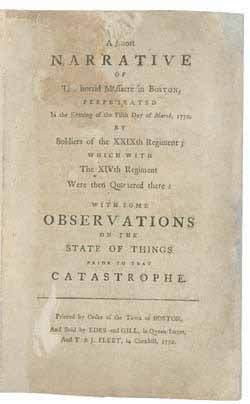

At this meeting James Bowdoin, Dr. Joseph Warren, and Samuel Pemberton reported that their analysis of “the execrable Massacre perpetrated on the Evening of the 5” was ready for printing. The town responded with an important vote:

whereas the publishing said Narrative with the Depositions accompanying it in this County, may be supposed by the unhappy Persons now in custody for tryal as tending to give an undue Byass to the minds of the Jury who are to try the same—The town would send copies of the report to advocates in London and sympathetic British politicians. As this letter shows, William Molineux sent a copy to Robert Treat Paine so he could prepare to prosecute the case. But the town meeting officially kept those books under wraps in America.

therefore Voted, that the Committee reserve all the printed Copies in their Hands excepting those to be sent to Great Britain ’till the further orders of the Town

Voted, that the Town Clerk [William Cooper] be directed not to give out Copies or deliver any of the Original Papers respecting the late horred Massacre; till the special order of the Town, or the direction of the Selectmen

On this same date, Josiah Quincy, Jr., told his father why he had agreed to defend Capt. Thomas Preston in court:

I at first declined being engaged; that after the best advice, and most mature deliberation had determined my judgment, I waited on Captain Preston, and told him I would afford him my assistance; but, prior to this, in presence of two of his friends, I made the most explicit declaration to him, of my real opinion, on the contests (as I expressed it to him) of the times, and that my heart and hand were indissolubly attached to the cause of my country; and finally, that I refused all engagement, until advised and urged to undertake it, by an Adams, a Hancock, a Molineux, a Cushing, a Henshaw, a Pemberton, a Warren, a Cooper, and a Phillips.Two of the three Short Narrative authors had urged Quincy to represent Preston, along with several of the town’s other leading politicians. Molineux, who had worked to build the case against Customs officer Edward Manwaring as being one of the shooters, nonetheless told Quincy to speak for the defense.

To make the town look good, to make any pardons seem unjust, and simply to be fair, the Boston Whigs wanted Capt. Preston, his soldiers, Manwaring, and even Ebenezer Richardson to have fair trials in Massachusetts courts.

And then to be hanged.

No comments:

Post a Comment