Springfield Armory National Historic Site and the Friends of Springfield Armory N.H.S. are organizing a one-day public symposium on Henry Knox, to be held on 6 May 2023.

As commander of artillery for the Continental Army, Knox recommended making Springfield the site of an arsenal and laboratory. That facility remained a federal armory in the early republic while Knox rose to be secretary of war.

The organizers have announced, “We invite scholars, historians, archivists, curators, and other interested parties to submit abstracts for short presentations that address Henry Knox and his role in American history.” These can include explorations of less admirable facets of this “complex and controversial man,” not just heroic portraits.

Presentations will be thirty minutes long (fifteen double-spaced pages when typed out) with ten minutes for questions. Up to eight proposals will be selected for the symposium.

Prospective presenters should send an abstract of no more than 500 words about their topic, including the presenter’s full name, contact information (name, title, organization, address, phone, email), and a 100-word biography. To send proposals, use the “email us” link on this page.

The due date for proposals is 8 March. By 22 March, the organizers will notify prospects if their proposals have been accepted. The presentations will be due on 19 April in order to ensure they will be ready for 6 May.

History, analysis, and unabashed gossip about the start of the American Revolution in New England.

▼

Tuesday, January 31, 2023

Monday, January 30, 2023

Matthew E. Henry‘s “self-evident”

Yesterday I went to a New England Poetry Club reading at the Fruitlands Museum in Harvard.

One of the poets sharing work was Matthew E. Henry, who is also a schoolteacher. He grew up in Boston and went to school in Wellesley, and in this poem he looked back on those years.

“self-evident” was a published first in the Tahoma Literary Review. It’s included in Henry’s collection The Colored Page, which on its webpage has the sell line: “How it started: Only Black kid in the room. Where we are: Only Black teacher in the building.”

One of the poets sharing work was Matthew E. Henry, who is also a schoolteacher. He grew up in Boston and went to school in Wellesley, and in this poem he looked back on those years.

self-evidentThe specific details, from the reminder of neighborhood enmities to the mention of Asa Pollard’s head, really evoke a post-Bicentennial Boston childhood. But they also remind us that nearby childhoods could be vastly different, then and now.

as a kid from Boston, the Revolutionary War

was my favorite subject in fourth grade.

a Tea Party I could respect. class trips vainly

searching for musket balls in Lexington treetops.

reading of decapitation by cannonball on Breed’s Hill.

even the sights in Southie— unsafe for me to visit—

were a source of tribal pride. like rooting for the Patriots.

we were told to don our colonial imagination caps

and tell our story of emancipation from the British.

where would we be? the Old South Meeting House?

the Old North Church? what would we see as we rose

to American greatness? our teacher should hear freedom

ringing in the streets through our words. I dropped my head

to begin— oversized pencil in hand— until I remembered.

seeing my inaction, she crouched and began to re-explain.

I patiently waited for her to finish, eyes on her lips,

then asked if she wanted me to pretend to be white,

or to picture myself for sale on the steps of Faneuil Hall,

or stacked in one-half of the Harbor ships heading to

and from the West Indies, explaining my parents’ patois.

after the vocal static— the hems and haws of white noise—

she suggested Crispus Attucks: the hometown boy, the Black

hero of the Boston Massacre. my siblings had taught me

the “one-drop rule,” and when to nod my head politely,

so I pretended he was not half Wampanoag, that Framingham

was not his master’s home, and imagined myself being

the first unarmed Black man shot on these urban streets.

“self-evident” was a published first in the Tahoma Literary Review. It’s included in Henry’s collection The Colored Page, which on its webpage has the sell line: “How it started: Only Black kid in the room. Where we are: Only Black teacher in the building.”

Sunday, January 29, 2023

Naming Names

In my recent sampling of historical fiction set in the Revolutionary period, I see authors having difficulty giving their characters authentic names.

Sometimes they fall into the trap of using given names familiar to us today but not in use then, such as “Suzanne” instead of “Susanna.” But more often writers go the other way and choose names that resonate with so much quaint historicity that we rarely see them today, such as “Norbert” or “Tristram”—but people of Revolutionary times didn’t see those names, either.

The problem is that the most common given names in Revolutionary times are quite familiar. Daniel Scott Smith showed this in a study of Massachusetts’s 1771 tax lists, published in the William & Mary Quarterly in 1994.

Among men, the names most frequently found were: John, Samuel, Joseph, William, Jonathan, Thomas, James, Benjamin, Daniel, and David.

Among women, the top names were: Mary, Elizabeth, Sarah, Hannah, Abigail, Lydia, Ann (or Anne or Anna), Rebecca, Martha, and Ruth.

All of those names are familiar today and have been familiar for a long time, meaning they don’t evoke any particular era. We have to go down the list to #11 for men and #12 for women before finding names we rarely use now: Ebenezer and Mehetabel.

What’s more, common names were more common in 1771—meaning that more of the men and women you met had the same popular given names. About 46% of all taxpaying men had one of those top-ten names listed above.

Among women, there was even less diversity. Slightly over two-thirds of all female taxpayers in Massachusetts shared the ten given names above. If you’ve ever done genealogy in this period, it feels like half of all the women are named Mary, Elizabeth, Sarah, Hannah, or Abigail. Smith’s number-crunching showed that’s actually a slight understatement. The correct figure is 52.8%.

In contrast, in the decades since World War 2, and especially in the decades since 1980, American parents have chosen an increasingly wider range of names, Sam Weinger reported through Medium. Notably, female names are now far more diverse than male names.

In 2014, a FiveThirtyEight article stated, “almost 30 percent of Americans have a given name that appears in the top 100 list.” Back in 1771, 30% of Massachusetts male taxpayers had a given name appearing in the top 5 list, and 27% of women were named either Mary or Elizabeth.

Sometimes they fall into the trap of using given names familiar to us today but not in use then, such as “Suzanne” instead of “Susanna.” But more often writers go the other way and choose names that resonate with so much quaint historicity that we rarely see them today, such as “Norbert” or “Tristram”—but people of Revolutionary times didn’t see those names, either.

The problem is that the most common given names in Revolutionary times are quite familiar. Daniel Scott Smith showed this in a study of Massachusetts’s 1771 tax lists, published in the William & Mary Quarterly in 1994.

Among men, the names most frequently found were: John, Samuel, Joseph, William, Jonathan, Thomas, James, Benjamin, Daniel, and David.

Among women, the top names were: Mary, Elizabeth, Sarah, Hannah, Abigail, Lydia, Ann (or Anne or Anna), Rebecca, Martha, and Ruth.

All of those names are familiar today and have been familiar for a long time, meaning they don’t evoke any particular era. We have to go down the list to #11 for men and #12 for women before finding names we rarely use now: Ebenezer and Mehetabel.

What’s more, common names were more common in 1771—meaning that more of the men and women you met had the same popular given names. About 46% of all taxpaying men had one of those top-ten names listed above.

Among women, there was even less diversity. Slightly over two-thirds of all female taxpayers in Massachusetts shared the ten given names above. If you’ve ever done genealogy in this period, it feels like half of all the women are named Mary, Elizabeth, Sarah, Hannah, or Abigail. Smith’s number-crunching showed that’s actually a slight understatement. The correct figure is 52.8%.

In contrast, in the decades since World War 2, and especially in the decades since 1980, American parents have chosen an increasingly wider range of names, Sam Weinger reported through Medium. Notably, female names are now far more diverse than male names.

In 2014, a FiveThirtyEight article stated, “almost 30 percent of Americans have a given name that appears in the top 100 list.” Back in 1771, 30% of Massachusetts male taxpayers had a given name appearing in the top 5 list, and 27% of women were named either Mary or Elizabeth.

Saturday, January 28, 2023

Fundraising for Security at Carpenters’ Hall

Carpenters’ Hall was built and owned by the Carpenters’ Company of the City and County of Philadelphia.

The guild started meeting in the building in 1771, though they continued working on it until 1775. By the fall of 1774 it was in good enough shape to host the First Continental Congress.

With delegates from twelve colonies participating, this was the broadest continental resistance gathering yet. It sent a petition to King George III, trying to go over the head of his ministers, and it called on Americans to adopt the Continental Association, a widespread boycott of British goods.

Later the Pennsylvania Provincial Conference and Convention met in Carpenters’ Hall to declare independence for that state, take control of the militia, and set up a new state constitution. (Meanwhile, the Second Continental Congress had taken over the nearby Pennsylvania State House, now called Independence Hall.)

Carpenters’ Hall remains the property of the Carpenters’ Company, but it’s also part of Independence National Historical Park, with National Park Service rangers leading free tours and programs.

For most of 2022, the building was closed for a $3 million renovation. It was due to reopen early this year.

On Christmas Eve, an N.P.S. officer discovered a fire in the building’s basement. Sprinklers went off, containing the flames, though that water harmed some files. Upper parts of the building sustained only smoke damage. Investigators determined the fire had been deliberately set.

The Carpenters’ Company has set up a Go Fund Me page for recovering from this arson, saying:

The guild started meeting in the building in 1771, though they continued working on it until 1775. By the fall of 1774 it was in good enough shape to host the First Continental Congress.

With delegates from twelve colonies participating, this was the broadest continental resistance gathering yet. It sent a petition to King George III, trying to go over the head of his ministers, and it called on Americans to adopt the Continental Association, a widespread boycott of British goods.

Later the Pennsylvania Provincial Conference and Convention met in Carpenters’ Hall to declare independence for that state, take control of the militia, and set up a new state constitution. (Meanwhile, the Second Continental Congress had taken over the nearby Pennsylvania State House, now called Independence Hall.)

Carpenters’ Hall remains the property of the Carpenters’ Company, but it’s also part of Independence National Historical Park, with National Park Service rangers leading free tours and programs.

For most of 2022, the building was closed for a $3 million renovation. It was due to reopen early this year.

On Christmas Eve, an N.P.S. officer discovered a fire in the building’s basement. Sprinklers went off, containing the flames, though that water harmed some files. Upper parts of the building sustained only smoke damage. Investigators determined the fire had been deliberately set.

The Carpenters’ Company has set up a Go Fund Me page for recovering from this arson, saying:

While insurance will cover much of the destruction, Carpenters' Hall will need to commit to new improvements to prevent another tragedy from occurring again in the future. Public donations will help to fund an improved security system, including new security cameras, fire protection systems, fireproof archival storage, and environmental protections for our collections.This effort seeks to raise $100,000 to preserve this historic building from future harm.

As we look towards the 250th anniversary of the First Continental Congress in just over a year, it is more vital than ever that we reopen the Hall as it was intended: as a meeting place for the community, a civic forum, and a building for the people.

Friday, January 27, 2023

“I am (as we say) a daughter of liberty”

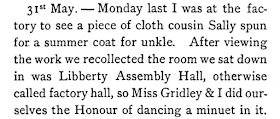

For a presentation this week that didn’t come off, I picked out three extracts from the letters of young teenager Anna Green Winslow to her mother in Nova Scotia, showing her political awakening. She wrote between November 1771 and May 1773.

Richard Gridley, retired artillery colonel, explained the political factions to Anna. As a girl, and an upper-class girl at that, Anna wasn’t supposed to demonstrate in the streets. But the Whig movement encouraged girls to participate in other ways, such as learning to spin so that local weavers could make more cloth so that local merchants didn’t have to import so much from Britain.

But Anna didn’t know how to spin.

So she contented herself by visiting the Manufactory where her cousin Sally’s yarn had been woven into cloth, and doing a little dance there. Anna could also participate in the movement as a consumer, choosing to buy more locally produced goods. In one letter she proudly described herself to her mother as a “daughter of liberty.” I’m not sure how Anna’s family felt about the politics she was learning in Boston. Her father, Joshua Winslow, was more closely allied with royal officials. Later in 1773 he lucked out (he thought) in being named one of the East India Company’s tea consignees in Boston. But when the town mobilized against allowing that tea to be landed, he had to lie low in Marshfield. Eventually, he left Massachusetts as a Loyalist.

Anna Green Winslow remained in the state, living in Hingham, but she died in 1780. Alas, outside of those letters to her mother in 1771–1773 we have almost no sources about Anna’s life, so we don’t know how her political outlook changed after the Whigs made her father an enemy for agreeing to sell tea, and after the war began.

Richard Gridley, retired artillery colonel, explained the political factions to Anna. As a girl, and an upper-class girl at that, Anna wasn’t supposed to demonstrate in the streets. But the Whig movement encouraged girls to participate in other ways, such as learning to spin so that local weavers could make more cloth so that local merchants didn’t have to import so much from Britain.

But Anna didn’t know how to spin.

So she contented herself by visiting the Manufactory where her cousin Sally’s yarn had been woven into cloth, and doing a little dance there. Anna could also participate in the movement as a consumer, choosing to buy more locally produced goods. In one letter she proudly described herself to her mother as a “daughter of liberty.” I’m not sure how Anna’s family felt about the politics she was learning in Boston. Her father, Joshua Winslow, was more closely allied with royal officials. Later in 1773 he lucked out (he thought) in being named one of the East India Company’s tea consignees in Boston. But when the town mobilized against allowing that tea to be landed, he had to lie low in Marshfield. Eventually, he left Massachusetts as a Loyalist.

Anna Green Winslow remained in the state, living in Hingham, but she died in 1780. Alas, outside of those letters to her mother in 1771–1773 we have almost no sources about Anna’s life, so we don’t know how her political outlook changed after the Whigs made her father an enemy for agreeing to sell tea, and after the war began.

Thursday, January 26, 2023

Davis on Ragsdale, Washington at the Plow

Camille Davis recently reviewed Bruce A. Ragsdale’s Washington at the Plow: The Founding Farmer and the Question of Slavery for H-Net.

Davis writes:

Davis writes:

Going beyond much of the historical analysis that presents farming as primarily an occupation that Washington held before the Revolution and a retirement activity that he reestablished after relinquishing command of the Continental Army, Ragsdale proves that farming was at the nexus of the first president’s personhood, an indelible component of his identity that he consistently developed. Additionally, Ragsdale uses Washington’s preoccupation with land ownership and cultivation to illuminate Washington’s decision-making processes as a slaveowner. Ragsdale believes Washington’s roles as landowner and slaveowner were inextricably linked.That overlap between what seem like the latest thinking and the most barbarous custom is provocative. Davis also notes some unanswered questions in Ragsdale’s analysis. Read the whole review here.

Ragsdale’s work illustrates that Washington’s preoccupation with agriculture was tied directly to the Enlightenment impetus of using science to assess, understand, and control one’s physical environment. Specifically, for Washington, this meant using scientific principles to improve soil conditions and crop growth. . . . As a private citizen, he continuously looked for ways to maximize the efficiency of enslaved persons working on his plantation. Additionally, he insisted that enslaved persons be kept aware of and trained on the most recent English farming techniques.

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

Researching Historic Carpentry

The North Bennet Street School (one of my mother’s multiple alma maters) just shared a blog post about graduates working at Colonial Williamsburg.

Of the alumni profiled, Jeremy Tritchler (shown above) and Brian Weldy studied in the Cabinet and Furniture Making program and Melanie Belongia in Violin Making—though she’s now applying those skills to harpsichords.

Tritchler was a geologist before trying the North Bennet Street School, and Belongia was a professional musician and law student. (My mother had also worked in several careers, in addition to raising two kids, when she decided to study piano tuning and repair.)

Today these three graduates are in the part of Colonial Williamsburg’s costumed staff who also work with wood and other eighteenth-century materials to produce cabinets, musical instruments, and other objects.

Meredith Fidrocki writes of Weldy, a master in the joiner’s shop:

Of the alumni profiled, Jeremy Tritchler (shown above) and Brian Weldy studied in the Cabinet and Furniture Making program and Melanie Belongia in Violin Making—though she’s now applying those skills to harpsichords.

Tritchler was a geologist before trying the North Bennet Street School, and Belongia was a professional musician and law student. (My mother had also worked in several careers, in addition to raising two kids, when she decided to study piano tuning and repair.)

Today these three graduates are in the part of Colonial Williamsburg’s costumed staff who also work with wood and other eighteenth-century materials to produce cabinets, musical instruments, and other objects.

Meredith Fidrocki writes of Weldy, a master in the joiner’s shop:

Projects require meticulous research. How did a colonial Joiner make this efficiently and economically? Figuring that out is one of Brian’s favorite parts of the job. “Not too many people can say they’ve crawled up in the steeple of the Bruton Parish Church,” he laughs, recalling up-close exploration of the 18th-century church on the museum grounds. “The beams come together in a beautiful latticework.” In the shop, he’s currently recreating one of the circular windows from the church.In fact, all three craftspeople speak of enjoying the research side of the job.

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

“Orders for the Lighting of the Lamps”

As I recounted yesterday, the official records of Boston’s selectmen from the end of August 1774 reveal that the town’s first street lamps, acquired at great expense and trouble just a few months before, were no longer being lit.

The immediate question was how the town would treat its contract with Edward Smith, hired back in March to oversee the lamplighters and maintain supplies. On 31 August the selectmen decided:

The decision to stop lighting the lamps coincided with the return of British army regiments to the streets. The presence of those soldiers didn’t make Bostonians feel so secure they decided street lighting was unnecessary. Based on their memories of 1768, citizens expected that having hundreds more young men in town, especially entitled young officers, would bring more trouble, not less.

At a meeting on 3 November, the town endorsed a recommendation to “augment the Town Watch to the Number of Twelve Men in each Watch” instead of four—a huge increase in personnel and expense.

That same town meeting took this confusing series of votes:

On 24 November, the selectmen chose one of their number, Timothy Newell, to “receive from John Rowe Esq. all the Lamps and Tin Plates which he has in his hands, and to deposite the same in the upper loft of Faneuil Hall.” Rowe (shown above) had chaired the committee to acquire and install the street lights, and now he was done with the project. The extra equipment went into Boston’s attic, not to be brought out until the lamps had been lit again.

The immediate question was how the town would treat its contract with Edward Smith, hired back in March to oversee the lamplighters and maintain supplies. On 31 August the selectmen decided:

Whereas it was agreed with Mr. Edward Smith to take the care of the Town Lamps for twelve months he to receive the sum of Forty Pounds Sterg. for that term of time, and whereas £13–6–8– lawful mony has been paid him for one quarter, & another quarter expires this day; but by reason of the distress occasioned by the Boston Port Bill, the Lamps have not been light the last Quarter—therefore,The town was thus still spending money on the street lights even though they weren’t lighting anything—and in a difficult economic time, too. But the selectmen could justify that as a payment for future service, and they kept Smith satisfied.

Voted, that mr. Smith have a draft for said last Quarter as tho’ the service had been performed he having engaged to perform said service in any future time when called upon for that purpose, it being his intention and agreement to perform the service at the rate he had engaged for a twelve month, when the Town shall think proper to have the Lamps again lighted; and to consider this 2d. Quarters pay as so much advanced on account of service, which remains still to be performed by him, when called upon for that purpose.

In the memo. Book he has signed his Name to such a Writing as the above.

The decision to stop lighting the lamps coincided with the return of British army regiments to the streets. The presence of those soldiers didn’t make Bostonians feel so secure they decided street lighting was unnecessary. Based on their memories of 1768, citizens expected that having hundreds more young men in town, especially entitled young officers, would bring more trouble, not less.

At a meeting on 3 November, the town endorsed a recommendation to “augment the Town Watch to the Number of Twelve Men in each Watch” instead of four—a huge increase in personnel and expense.

That same town meeting took this confusing series of votes:

Upon a Motion made, Voted, that the Selectmen be desired to give Orders for the Lighting of the Lamps, when they shall think it proper.——That appears to be the last recorded discussion of the street lamps before the war. Presumably they remained dark.

Voted, that a Comittee be now chosen to procure Subscriptions for the Purpose of Lighting of the Town Lamps.

On a Motion made, Voted, that the above Vote respecting Subscriptions for lighting the Lamps be reconsidered

On 24 November, the selectmen chose one of their number, Timothy Newell, to “receive from John Rowe Esq. all the Lamps and Tin Plates which he has in his hands, and to deposite the same in the upper loft of Faneuil Hall.” Rowe (shown above) had chaired the committee to acquire and install the street lights, and now he was done with the project. The extra equipment went into Boston’s attic, not to be brought out until the lamps had been lit again.

Monday, January 23, 2023

When the Lights Went Out in Boston

The latest episode of the fine HUB History podcast focused on how Boston installed its first street lamps in 1773 and 1774, the effort hampered by the equipment being wrecked on Cape Cod along with some East India Company tea.

The discussion doesn’t end with those whale-oil lamps but traces the changes in illumination technology to today. Along the way, we learn that the “historic” street lamps now decorating certain Boston neighborhoods are far younger than most people assume.

The podcast’s story of the first street lamps draws heavily on the records of Boston’s town meeting and the journal of John Rowe, the merchant put in charge of the lamp committee.

Here’s another aspect of the story, preserved in the records of Boston’s selectmen. Each year’s first town meeting chose those seven officials to carry out ordinary business and deal directly with contractors.

On 1 March, those officials recorded:

Three months later, on 1 June, the selectmen met with the lamplighters themselves, named as “Messrs. Barker, Fowle, Stevens, Wm. & Thomas Sharp, Hoadly, & Ayres.” Those men “agreed with the Selectmen that they would continue Lamp Lighters thro’ the Winter.”

But bigger questions were roiling the town. On 13 May there was a meeting to hear the new Boston Port Bill and formulate a response to it. That discussion continued through meeting after meeting all summer. Almost everyone agreed that the Port Bill was a constitutional affront and an economic disaster. And, of course, alongside Parliament’s new law, companies of British army regulars were once again marching on Boston streets.

One response to the law was not to light those new street lamps after all. There’s no record of a decision, nor report in the newspapers. But on 24 August Edward Smith “apply’d to the Selectmen and acquainted them he expected to be paid according to Agreement although the Lamps had not been lighted the last Quarter.”

At the end of the month the selectmen’s records confirmed: “by reason of the distress occasioned by the Boston Port Bill, the Lamps have not been light the last Quarter.”

As the HUB History episode recounts, although the town governed the process of installing and maintaining the street lamps, it didn’t undertake to pay for them through taxes. Instead, Boston asked wealthy citizens to donate money for that effort. Enough money had come in the buy the lamps, install them, and hire staff to maintain them.

But with the Port Bill straining the town’s trade with Britain and other colonies, those wealthy citizens might have felt they couldn’t afford to pay for street lamps after all. Or perhaps people felt the illumination clashed with the somber, resentful mood of a town protesting arbitrary law and military occupation. Maybe the longer days of midyear made it easier to do without street lighting. With no visible decision point, it’s impossible to know for sure why the lamps weren’t lit and who made that choice.

(We do know that, since the lamps went dark in June, that decision had nothing to do with the ‘arms race’ that broke out in September, with Patriots trying to smuggle artillery and other weapons of war out of Boston and the British military trying to stop them. When I wrote about that conflict in The Road to Concord, I wondered if dark streets made moving cannon around at night easier, but that could only be conjecture.)

TOMORROW: Making choices in the dark.

The discussion doesn’t end with those whale-oil lamps but traces the changes in illumination technology to today. Along the way, we learn that the “historic” street lamps now decorating certain Boston neighborhoods are far younger than most people assume.

The podcast’s story of the first street lamps draws heavily on the records of Boston’s town meeting and the journal of John Rowe, the merchant put in charge of the lamp committee.

Here’s another aspect of the story, preserved in the records of Boston’s selectmen. Each year’s first town meeting chose those seven officials to carry out ordinary business and deal directly with contractors.

On 1 March, those officials recorded:

It was agreed with Edward Smyth to have £40— Sterg. for one year, for overseeing the Lamps & Lamplighters & delivering the Oyle & Wicks & other necessary.Smith (as the name was more often written) got paid £13.6.8 for the first quarter of the year, March through May. (No, I don’t know why the town paid Smith a third of his annual salary to cover a quarter of the year.)

Three months later, on 1 June, the selectmen met with the lamplighters themselves, named as “Messrs. Barker, Fowle, Stevens, Wm. & Thomas Sharp, Hoadly, & Ayres.” Those men “agreed with the Selectmen that they would continue Lamp Lighters thro’ the Winter.”

But bigger questions were roiling the town. On 13 May there was a meeting to hear the new Boston Port Bill and formulate a response to it. That discussion continued through meeting after meeting all summer. Almost everyone agreed that the Port Bill was a constitutional affront and an economic disaster. And, of course, alongside Parliament’s new law, companies of British army regulars were once again marching on Boston streets.

One response to the law was not to light those new street lamps after all. There’s no record of a decision, nor report in the newspapers. But on 24 August Edward Smith “apply’d to the Selectmen and acquainted them he expected to be paid according to Agreement although the Lamps had not been lighted the last Quarter.”

At the end of the month the selectmen’s records confirmed: “by reason of the distress occasioned by the Boston Port Bill, the Lamps have not been light the last Quarter.”

As the HUB History episode recounts, although the town governed the process of installing and maintaining the street lamps, it didn’t undertake to pay for them through taxes. Instead, Boston asked wealthy citizens to donate money for that effort. Enough money had come in the buy the lamps, install them, and hire staff to maintain them.

But with the Port Bill straining the town’s trade with Britain and other colonies, those wealthy citizens might have felt they couldn’t afford to pay for street lamps after all. Or perhaps people felt the illumination clashed with the somber, resentful mood of a town protesting arbitrary law and military occupation. Maybe the longer days of midyear made it easier to do without street lighting. With no visible decision point, it’s impossible to know for sure why the lamps weren’t lit and who made that choice.

(We do know that, since the lamps went dark in June, that decision had nothing to do with the ‘arms race’ that broke out in September, with Patriots trying to smuggle artillery and other weapons of war out of Boston and the British military trying to stop them. When I wrote about that conflict in The Road to Concord, I wondered if dark streets made moving cannon around at night easier, but that could only be conjecture.)

TOMORROW: Making choices in the dark.

Sunday, January 22, 2023

Four Million Pounds of Leaves

At the Regency Explorer, Anna M. Thane shared information about a problem I hadn’t consider: counterfeit tea.

That doesn’t mean the labrador and other herbal infusions that Whig leaders like Dr. Thomas Young promoted as a substitute for tea during the boycott 250 years ago.

Rather, this problem was leaves of other plants sold as genuine tea in Britain. According to Thane:

In 1820 a chemist named Frederick Accum published A Treatise on Adulterations of Food, and Culinary Poisons in London describing the tricks of making counterfeit tea and also the ways of testing the leaves one had bought to make sure they were genuine.

Check out the Regency Explorer for that vital information. Seems like it might be especially useful for a mystery novelist.

That doesn’t mean the labrador and other herbal infusions that Whig leaders like Dr. Thomas Young promoted as a substitute for tea during the boycott 250 years ago.

Rather, this problem was leaves of other plants sold as genuine tea in Britain. According to Thane:

A government report states in 1783 that the quantity of fictitious tea made from sloe and ash-tree leaves sums up to more than four million pounds (compare to the whole quantity of genuine tea sold by the East India Company: about 6 million pounds per year).For consumers the problem wasn’t just not getting the tea (and caffeine) they expected. Turning sloe and ash-tree leaves into something that looked like black tea started with boiling them with verdigris, which was poisonous. For green tea, the leaves would be colored with the same substance. Also, sloe was known as a purgative.

In 1820 a chemist named Frederick Accum published A Treatise on Adulterations of Food, and Culinary Poisons in London describing the tricks of making counterfeit tea and also the ways of testing the leaves one had bought to make sure they were genuine.

Check out the Regency Explorer for that vital information. Seems like it might be especially useful for a mystery novelist.

Saturday, January 21, 2023

Fort Ti War College of the Seven Years’ War, 19–21 May

Fort Ticonderoga is holding its Twenty-Seventh Annual War College of the Seven Years’ War on the weekend of 19–21 May.

This will be a hybrid conference, so fans of the conflict can attend in upstate New York or watch online.

The scheduled presentations reflect that war’s reputation as a global conflict, bringing scholars from multiple countries.

Friday, 19 May

This day’s presenters are all graduate students sharing their new research.

Basic registration is $175, but there are discounts for being a Fort Ti member, registering early, and participating online instead of on-scene, so a member like myself can listen to the presentations for as little as $100. There are also scholarships for teachers who are attending the War College of the Seven Years’ War for the first time. Check out the whole registration scheme at this webpage.

This will be a hybrid conference, so fans of the conflict can attend in upstate New York or watch online.

The scheduled presentations reflect that war’s reputation as a global conflict, bringing scholars from multiple countries.

Friday, 19 May

- Matthew Keagle, Fort Ticonderoga Curator, “Highlights from the Robert Nittolo Collection”

- Ellen Fogel Walker, Public Affairs Coordinator at Culloden Battlefiel, “Anchors for Collective Identity: Culloden Militaria of the ’45, Artefacts and Memorabilia”

- Jay Donis, professor at Thiel College, “Building an American Identity on the Mid-Atlantic Frontier in the 1760s”

- James Kirby Martin, coauthor of Forgotten Allies, “The Six Nations Confronts the French and Indian War: Joseph Brant Versus Han Yerry”

- Ian McCulloch, former Director of the Canadian Forces’ Centre for National Security Studies, “John Bradstreet’s Raid 1758: A Revisionist Assessment”

- Djordje Djuric, professor at the Faculty of Philosophy in Novi Sad, “Simeon Piscevic (Simeon Piščević), General and Diplomat of the Era of the Seven Years’ War”

This day’s presenters are all graduate students sharing their new research.

- Jenifer Ishee, Mississippi State University, “Captive Bodies: Examining the Material Culture of Captivity during the Seven Years’ War”

- Clément Monseigne, Bordeaux University, “Feeling Strangeness: the Sensory Experience of War in North America (1754-1760)”

- Daniel Bishop, Texas A&M University, “‘Lay’d up And Decay’d’: Examining the History and Archaeological Material of the King’s Shipyard at Fort Ticonderoga”

- Camden R. Elliott, Harvard University, “‘That Most Fatal disorder to the Virginians’: The Seven Years’ War and a Pandemic of Smallpox, 1756-1766”

Basic registration is $175, but there are discounts for being a Fort Ti member, registering early, and participating online instead of on-scene, so a member like myself can listen to the presentations for as little as $100. There are also scholarships for teachers who are attending the War College of the Seven Years’ War for the first time. Check out the whole registration scheme at this webpage.

Friday, January 20, 2023

A Likely Addition to Phillis Wheatley’s Works

Prof. Wendy Raphael Roberts of the University of Albany has announced the discovery of a previously unknown poem by Phillis Wheatley, “On the Death of Love Rotch.”

Or, as this press release from the university says, Roberts found a poem in the 1782 commonplace book of Mary Powel Potts (1769–1787) of Pennsylvania, the lines dated to 1767 and attributed to “A Negro Girl about 15 years of age.”

Since we know of only one teen-aged girl of African descent writing poetry in British North America at the time, Phillis Wheatley is the most likely candidate.

Of course, a few years ago we assumed that the black portrait artist advertising in Boston newspapers 250 years ago this season had to be Scipio Moorhead, since he was the only possibility to appear in the published sources. (In fact, one of the main sources about him is a poem by Phillis Wheatley.)

But then Paula Bagger put together manuscript sources (including letters I quoted back here) to bring out the life of Prince Demah, now almost certainly the portraitist in those advertisements.

Thus, while it would be unlikely that two African girls were writing poetry in New England in 1767, it’s not impossible.

There are, however, some additional clues pointing to Wheatley:

There are still some mysteries. For one:

Another open question:

Or, as this press release from the university says, Roberts found a poem in the 1782 commonplace book of Mary Powel Potts (1769–1787) of Pennsylvania, the lines dated to 1767 and attributed to “A Negro Girl about 15 years of age.”

Since we know of only one teen-aged girl of African descent writing poetry in British North America at the time, Phillis Wheatley is the most likely candidate.

Of course, a few years ago we assumed that the black portrait artist advertising in Boston newspapers 250 years ago this season had to be Scipio Moorhead, since he was the only possibility to appear in the published sources. (In fact, one of the main sources about him is a poem by Phillis Wheatley.)

But then Paula Bagger put together manuscript sources (including letters I quoted back here) to bring out the life of Prince Demah, now almost certainly the portraitist in those advertisements.

Thus, while it would be unlikely that two African girls were writing poetry in New England in 1767, it’s not impossible.

There are, however, some additional clues pointing to Wheatley:

- Wheatley often wrote memorial verse like this elegy, particularly when she was starting out. She didn’t necessarily know the people she wrote about.

- The title and date of this poem match the details of Love (Macy) Rotch, a Quaker on Nantucket, who died 14 Nov 1767.

- Wheatley wrote “To a Gentleman on his Voyage to Great Britain for the Recovery of his Health” to Love Rotch’s son Joseph, Jr., reportedly in or before 1767. (Boston newspapers reported in March 1773 that he had died in England.)

- Love Rotch’s other sons, William and Francis, owned the ship Dartmouth, which carried the first edition of Wheatley’s poems back to Boston in 1773.

- We know Wheatley’s poems circulated in manuscript and commonplace books among Philadelphia Quaker women like Mary Powel Potts.

There are still some mysteries. For one:

The only thing that didn’t make sense to Roberts was the copyist’s claim that Love Rotch was the poet’s mistress, since it was widely known that Susanna Wheatley held that role.Roberts apparently suggests that the Wheatley family loaned or rented Phillis to the Rotch family. That strikes me as a more complex, less likely explanation than that Potts or her teacher misunderstood the origin of the poem and assumed it reflected the author’s lament for someone she knew well.

Another open question:

Roberts found another anonymous poem in the Potts book that she believes Wheatley wrote but can only speculatively attribute to her. Titled “The Black Rose,” it mourns the death of a Black woman named Rose and uses theology to critique a society that refused to mourn the enslaved and oppressed. It would be the only known elegy Wheatley wrote for a Black woman.Also a mystery in the press release is the actual text of these poems. Those will presumably appear with Prof. Roberts’s analysis in the upcoming Early American Literature article. On Thursday, 26 January, at 6:00 P.M., the Library Company of Philadelphia will host a virtual talk by Roberts on “A Newly Unearthed Poem by Phillis Wheatley (Peters) and the Future of the Wheatley Canon.”

Thursday, January 19, 2023

“The Hive” in Concord, 18–19 Feb.

On the weekend of 18–19 February, Minute Man National Historical Park, Friends of Minute Man, Revolution 250, and the Massachusetts Army National Guard will host this year’s edition of “The Hive: A Symposium for Living History Interpreters.”

The 2023 Hive will offer two straight days of presentations and workshops on the start of the American Revolution, geared toward eighteenth-century reenactors and living-history interpreters.

As in past years, these sessions are designed to improve the accuracy of people’s portrayals of that past, particularly for the commemorations of the Battle of Lexington and Concord in April but beyond that as well.

That concern for accuracy in costuming, weapons, and other material culture is why the continuously improving “Battle Road Standards” are a benchmark for Revolutionary reenactments. But it’s also valuable to understand the political issues, the social milieu, and the ordinary customs of the time when interacting with the public.

This year the Hive will take place at the Massachusetts National Guard Armory in Concord. The schedule is still being filled out, but some of the planned presentations are:

For more information about this free event for dedicated reenactors (and those curious about being dedicated), visit the park’s webpage.

The 2023 Hive will offer two straight days of presentations and workshops on the start of the American Revolution, geared toward eighteenth-century reenactors and living-history interpreters.

As in past years, these sessions are designed to improve the accuracy of people’s portrayals of that past, particularly for the commemorations of the Battle of Lexington and Concord in April but beyond that as well.

That concern for accuracy in costuming, weapons, and other material culture is why the continuously improving “Battle Road Standards” are a benchmark for Revolutionary reenactments. But it’s also valuable to understand the political issues, the social milieu, and the ordinary customs of the time when interacting with the public.

This year the Hive will take place at the Massachusetts National Guard Armory in Concord. The schedule is still being filled out, but some of the planned presentations are:

- Bob Allison, “Why Did the Revolution Happen?”

- Michele Gabrielson, “A Pressing Matter: Media Literacy & 18th-Century Newspapers”

- Henry Cooke, “Introduction to Men’s Clothing”

- Ruth Hodges, “Introduction to Women’s Clothing”

- Paul O’Shaughnessy, “Basic Musket Maintenance”

- Jim Hollister, “Interpretive Skills Workshop”

- Larissa Sasgen, “Essential Stitches for Beginners”

- Niels Hobbs, “Re-fit Your Kit: Things that Bring Your Impression to the Next Level”

- Adam Hodges LeClaire, “Portraying the Lower Sort”

- Alex Cain and Joel Bohy, “Militia Equipment in 1775”

For more information about this free event for dedicated reenactors (and those curious about being dedicated), visit the park’s webpage.

Wednesday, January 18, 2023

Dublin Seminar Call for Papers on “Indigenous Histories”

The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife has announced the subject of its June 2023 conference: “Indigenous Histories in New England: Pastkeepers and Pastkeeping.”

The seminar’s call for papers says:

For more detail on how to propose a paper, go to the Dublin Seminar webpage. The program and registration details for this conference will also appear on the Dublin Seminar website in the spring.

The seminar’s call for papers says:

Three decades have passed since the 1993 publication of the Seminar’s proceedings Algonkians of New England. Over that space of time, both the study of Indigenous histories in the region (encompassing present-day New England and adjacent areas of New York and Canada), and understanding of the memory work of pastkeepers and pastkeeping, have been transformed. The 2023 Seminar Indigenous Histories in New England: Pastkeepers and Pastkeeping will explore long traditions of Indigenous pastkeeping and the wide variety of ways in which Native peoples have stewarded history and memory.The Seminar will convene at Historic Deerfield on 23–24 June. It will be a hybrid program, with both on-site and virtual registration options for attendees.

The Seminar invites proposals for papers that focus on addressing the gaps in Indigenous voice and visibility in public views of the past. We wish to critically consider who has claimed responsibility for “keeping” the Indigenous past in New England, including how it has been represented (for better or worse), how historical research can be decolonized and improved, and what museums and tribal nations have done to engage the public in better understandings.

Papers offering historical perspective might explore, for instance:The Seminar will give particular attention to the work of museums, archives, historic preservation organizations, cultural centers, and initiatives that over the past thirty years have worked to provide more holistic and inclusive representations of regional Indigenous peoples and histories.

- Indigenous forms of memory-making and pastkeeping, on landscapes and in oral tradition

- Native American authors of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth century, including autobiography and tribal histories

- collections of material culture; histories of tribal museums

- repatriation and cultural recovery

- language reclamation

- artwork as vehicles for historical reflection

For more detail on how to propose a paper, go to the Dublin Seminar webpage. The program and registration details for this conference will also appear on the Dublin Seminar website in the spring.

Tuesday, January 17, 2023

History Camp Valley Forge, 19–21 May

The History Camp organization has opened registration for events in and around Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, on 19–21 May.

History Camp Valley Forge offers three events with separate sign-ups, so people can choose which they want to attend.

Friday, 19 May

Forging the Continental Army

This is a limited-enrollment, all-day symposium at Valley Forge featuring talks by speakers recruited for their expertise on that site:

Saturday, 20 May

History Camp Valley Forge

This day will be a history camp of the sort established in Boston in 2014. Anyone can propose a presentation on any historical topic, with proposals due by 10 April. Organizers will choose a slate of sessions, seeking to maximize interest, variety, and enthusiastic and experienced presenters. The schedule will be announced shortly before the day, and attendees choose which of the many talks to attend. Light breakfast and lunch are included with registration. (Attendees can also continue their discussions at a nearby inn in the evening, paying their own tab.)

Some of the sessions are already listed on the webpage, and those with Revolutionary links include:

Sunday, 21 May

Tours of Revolutionary Philadelphia

Starting at 8:30 on Sunday morning, attendees will take a coach tour to see the Anthony Wayne house in Waynesborough and then on to Philadelphia for three tours led by National Park Service rangers:

History Camp Valley Forge offers three events with separate sign-ups, so people can choose which they want to attend.

Friday, 19 May

Forging the Continental Army

This is a limited-enrollment, all-day symposium at Valley Forge featuring talks by speakers recruited for their expertise on that site:

- Phillip Greenwalt, author of The Winter that Won the War

- Mark Edward Lender, author of Cabal!: The Plot Against General Washington

- Richard Bell, author of a forthcoming book on Gen. Steuben

- Nancy K. Loane, author of Following the Drum: Women at the Valley Forge Encampment

- Ken Gavin, leading a tour by coach and foot of the Valley Forge camp

Saturday, 20 May

History Camp Valley Forge

This day will be a history camp of the sort established in Boston in 2014. Anyone can propose a presentation on any historical topic, with proposals due by 10 April. Organizers will choose a slate of sessions, seeking to maximize interest, variety, and enthusiastic and experienced presenters. The schedule will be announced shortly before the day, and attendees choose which of the many talks to attend. Light breakfast and lunch are included with registration. (Attendees can also continue their discussions at a nearby inn in the evening, paying their own tab.)

Some of the sessions are already listed on the webpage, and those with Revolutionary links include:

- Michael Troy of the American Revolution Podcast, “The Philadelphia Bible Riots of 1844”

- Jerry Landry of the Presidencies of the United States podcast on Dolley Madison

- Bil Lewis, James Madison interpreter, ”Madison v. Hamilton”

- Salina Baker, historical novelist, on Gen. Nathanael Greene

- Matthew Mees, Revolutionary-era interpreter, “French Siege Craft in America”

Sunday, 21 May

Tours of Revolutionary Philadelphia

Starting at 8:30 on Sunday morning, attendees will take a coach tour to see the Anthony Wayne house in Waynesborough and then on to Philadelphia for three tours led by National Park Service rangers:

- “The Room Where it Happened” at Independence National Historical Park

- “The British Occupation of Philadelphia” walking tour

- “Dr. Franklin’s Philadelphia” walking tour

Monday, January 16, 2023

“Poor Mrs. Macaulay! She is irrecoverably fallen.”

In October 1778, the historian Catharine Macaulay left Bath and the home she shared with the Rev. Thomas Wilson.

One possible reason for Macaulay’s move was that Wilson kept pressing her to marry him. Everyone knew the minister was besotted with the widowed author. He’d already signed over a lease to his house, erected a statue in London, and published a book of fawning poetry. But she declined to make him her second husband.

As Bob Ruppert described in this Journal of the American Revolution article, Macaulay moved across England to Leicester in the East Midlands. That was the city where her friend Elizabeth Arnold lived.

Arnold was the sister of Macaulay’s physician, Dr. James Graham, and wife of another physician who managed an asylum for the mentally ill. The two women had visited France together in late 1777.

On 14 November, a minister in Leicester married Macaulay to Dr. Graham. Not James Graham, who was with his wife and children in Scotland. That would have provided plenty of scandal and confirmed a rumor that John Wilkes had recorded earlier in the year.

Rather, the historian married William Graham, younger brother of Dr. James Graham and Elizabeth Arnold.

Much younger brother, in fact. William Graham was only twenty-one years old. He was barely a doctor, having studied in Edinburgh and trained as a surgeon’s mate for the East India Company.

Even by the modern standard of “half your age plus seven,” William Graham seemed “too young” for Macaulay, who was forty-seven. And of course Macaulay was a woman. A woman who had put herself into the public eye by writing about history and politics.

The reaction was swift and negative. One acquaintance at Bath, Edmund Rack, wrote to Richard Polwhele, an eighteen-year-old admirer of the historian, on 29 December:

COMING UP: More reactions.

[The portrait of “Mrs. Catherine M’Caulay” above is a woodcut printed in Nathaniel Ames’s Astronomical Diary; or Almanack for 1772. Paul Revere supplied versions of this cut to both Ezekiel Russell and Edes and Gill for their competing editions. Printing this illustration of Macaulay shows the admiration, or at least curiosity, that she inspired in New England at that time. (The almanac’s other images featured John Dickinson and the dwarf Emma Leach.) This image comes courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.]

One possible reason for Macaulay’s move was that Wilson kept pressing her to marry him. Everyone knew the minister was besotted with the widowed author. He’d already signed over a lease to his house, erected a statue in London, and published a book of fawning poetry. But she declined to make him her second husband.

As Bob Ruppert described in this Journal of the American Revolution article, Macaulay moved across England to Leicester in the East Midlands. That was the city where her friend Elizabeth Arnold lived.

Arnold was the sister of Macaulay’s physician, Dr. James Graham, and wife of another physician who managed an asylum for the mentally ill. The two women had visited France together in late 1777.

On 14 November, a minister in Leicester married Macaulay to Dr. Graham. Not James Graham, who was with his wife and children in Scotland. That would have provided plenty of scandal and confirmed a rumor that John Wilkes had recorded earlier in the year.

Rather, the historian married William Graham, younger brother of Dr. James Graham and Elizabeth Arnold.

Much younger brother, in fact. William Graham was only twenty-one years old. He was barely a doctor, having studied in Edinburgh and trained as a surgeon’s mate for the East India Company.

Even by the modern standard of “half your age plus seven,” William Graham seemed “too young” for Macaulay, who was forty-seven. And of course Macaulay was a woman. A woman who had put herself into the public eye by writing about history and politics.

The reaction was swift and negative. One acquaintance at Bath, Edmund Rack, wrote to Richard Polwhele, an eighteen-year-old admirer of the historian, on 29 December:

Poor Mrs. Macaulay! She is irrecoverably fallen. “Frailty, thy name is Woman!” Her passions, even at 52 [sic], were too strong for her reason; and she has taken to bed a stout brawny Scotchman of 21. For shame! Her enemies’ triumph is now complete. Her friends can say nothing in her favour. O, poor Catharine!—never canst thou emerge from the abyss into which thou art fallen!And that was one of the more sympathetic responses.

COMING UP: More reactions.

[The portrait of “Mrs. Catherine M’Caulay” above is a woodcut printed in Nathaniel Ames’s Astronomical Diary; or Almanack for 1772. Paul Revere supplied versions of this cut to both Ezekiel Russell and Edes and Gill for their competing editions. Printing this illustration of Macaulay shows the admiration, or at least curiosity, that she inspired in New England at that time. (The almanac’s other images featured John Dickinson and the dwarf Emma Leach.) This image comes courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.]

Sunday, January 15, 2023

“The highest dispenser of human fame, Mr. Johnson’s pocket book”

In late 1777, around the time the British historian Catharine Macaulay was visiting France for her health, she appeared in an engraving.

Macaulay was a celebrity, so she had been depicted in many engravings—some admiring, some satirical. But this picture was unusual.

It was a group portrait titled The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain, drawn by Richard Samuel and engraved by someone named Walker. It appeared as a foldout in The Ladies New and Polite Pocket Memorandum-Book, for the Year of Our Lord 1778, published in London by Joseph Johnson.

The print showed nine women in vaguely classical costume engaged in different arts: music, painting, and so on. The caption below identified those women as:

Samuel completed a painting based on the same composition and exhibited it at the Royal Academy in 1779. As shown above, it now belongs to Britain’s National Portrait Gallery.

As portraiture, however, those pictures aren’t very good. Without the engraving’s caption, it would be impossible to connect the nine figures in the painting to the actual writers and artists. On 23 November, one of those women, poet and translator Elizabeth Carter (1717–1806), wrote to another, Blue Stockings Society hostess Elizabeth Montagu (1720–1800):

Still, this image reflects Macaulay’s place in British culture at the start of 1778. She was not only a celebrated historian, but she was being held up as the nation’s answer to the Muse of History herself.

And then it all came crashing down.

TOMORROW: A step too far.

Macaulay was a celebrity, so she had been depicted in many engravings—some admiring, some satirical. But this picture was unusual.

It was a group portrait titled The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain, drawn by Richard Samuel and engraved by someone named Walker. It appeared as a foldout in The Ladies New and Polite Pocket Memorandum-Book, for the Year of Our Lord 1778, published in London by Joseph Johnson.

The print showed nine women in vaguely classical costume engaged in different arts: music, painting, and so on. The caption below identified those women as:

Miss Carter, Mrs. Barbauld, Mrs. Angelica Kauffman, on the Right hand; Mrs. Sheridan, in the Middle; Mrs. Lenox, Mrs. Macaulay, Miss More, Mrs. Montague, and Mrs. Griffith, on the Left hand.These were all British women who had gained fame for some kind of writing, painting, or musical performances.

Samuel completed a painting based on the same composition and exhibited it at the Royal Academy in 1779. As shown above, it now belongs to Britain’s National Portrait Gallery.

As portraiture, however, those pictures aren’t very good. Without the engraving’s caption, it would be impossible to connect the nine figures in the painting to the actual writers and artists. On 23 November, one of those women, poet and translator Elizabeth Carter (1717–1806), wrote to another, Blue Stockings Society hostess Elizabeth Montagu (1720–1800):

O Dear, O dear, how pretty we look, and what brave things has Mr. Johnson said of us! Indeed, my dear friend, I am just as sensible to present fame as you can be. Your Virgils and your Horaces may talk what they will of posterity, but I think it is much better to be celebrated by the men, women, and children, among whom one is actually living and looking.As for Catharine Macaulay, she had an unusual face, already captured in those many engravings and at least one statue. By this date she was in her late forties, a widow, not in good health. But the figure of Clio, Muse of History, holding a scroll toward the center of the pictures doesn’t exhibit any of those personal features.

One thing is very particularly agreeable to my vanity, to say nothing about my heart, that it seems to be a decided point, that you and I are always to figure in the literary world together, and that from the classical poet, the water drinking rhymes, to the highest dispenser of human fame, Mr. Johnson’s pocket book, it is perfectly well understood, that we are to make our appearance in the same piece. I am mortified, however, that we do not in this last display of our persons and talents stand in the same corner.

As I am told we do not, for to say truth, by the mere testimony of my own eyes, I cannot very exactly tell which is you, and which is I, and which is any body else. But this must arise from the deficiency of my sight, for some of the good people of Deal, I am told, affirm my picture to be excessively like.

Still, this image reflects Macaulay’s place in British culture at the start of 1778. She was not only a celebrated historian, but she was being held up as the nation’s answer to the Muse of History herself.

And then it all came crashing down.

TOMORROW: A step too far.

Saturday, January 14, 2023

“As rotten as an old Catherine pear”

In April 1778, John Wilkes was back at Bath (if he had ever left). On the 28th he wrote to his daughter Polly about the well known author Catharine Macaulay:

The “new caricature” from Darly was evidently the one at the bottom of this post, showing Macaulay stalked by death while she applied makeup. That picture also included Wilson’s profile.

Wilkes knew that Macaulay didn’t like that portrayal. Nevertheless, he recommended that his daughter buy the picture.

And then a few lines later Wilkes wrote: “To-day I dine with Mrs. Macaulay and the Doctor.”

What a delightful man.

TOMORROW: A more flattering, less recognizable picture.

Yesterday we went to Kitty Macaulay, as she is still called. She looked as rotten as an old Catherine pear. Lord I[rnham]. was disgusted with her manner, &c.Back in May 1777, the artist Mattina Darly had published a cartoon of Macaulay writing while the Rev. Dr. Thomas Wilson looked on, titled “The Historians.” Behind them was a bust of Alfred the Great, reflecting both Whiggish admiration for that early king and how the minister had named his mansion Alfred House. The image above comes courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library.

Darley has just published a new caricature of her and the Doctor, which she owns has vexed her to the heart. It is worth your buying.

The “new caricature” from Darly was evidently the one at the bottom of this post, showing Macaulay stalked by death while she applied makeup. That picture also included Wilson’s profile.

Wilkes knew that Macaulay didn’t like that portrayal. Nevertheless, he recommended that his daughter buy the picture.

And then a few lines later Wilkes wrote: “To-day I dine with Mrs. Macaulay and the Doctor.”

What a delightful man.

TOMORROW: A more flattering, less recognizable picture.

Friday, January 13, 2023

John Wilkes’s Gossip about “Kitty Macaulay”

Catharine Macaulay was a celebrity in Britain, so her return from France at the start of 1778 attracted notice.

John Wilkes was in Bath when Macaulay arrived home. He wrote to his 28-year-old daughter Mary (called Polly, and shown here with dad) on 4 January:

TOMORROW: Wilkes gives unabashed gossip a bad name.

John Wilkes was in Bath when Macaulay arrived home. He wrote to his 28-year-old daughter Mary (called Polly, and shown here with dad) on 4 January:

Mrs. Macaulay returned to Dr. [Thomas] Wilson on Friday. I saw her yesterday very ill indeed, and raving against France and everything in that country. She even says their soups are detestable, as bad as Lacedemonian black broth, and their game insipid, all their meat bad, and their poultry execrable. Yet she says, that she dined at some of the best tables and was infinitely caressed.Three days later Wilkes told his daughter that his health had improved and he was thinking about returning to London. He added:

She saw Dr. [Benjamin] Franklin, but refused his invitation to dinner, for fear of being confined on her return in consequence of the Habeas Corpus Act.

“Lord J——s C——t, Mr. Wilkes, you know, I am very fond of partridges. I saw them often served up, but could not eat them, I found them so hard and ill-flavoured.[”]

I stayed with her nearly an hour, in which time, I believe, she exclaimed twenty times, [“]Lord J——s C——t.” She was painted up to the eyes, and looks quite ghastly and ghostly. She has sent away her English woman, and has only a French valet-de-chambre and friseur, at which the reverend Doctor is indignant, and with whom the English servants already quarrel.

The rage of politics is, I think, more violent at Bath than even at London, and nothing is talked of but America, except Kitty Macaulay, who grows worse daily. The doctor [Wilson] looks stupid and sulky.And the day after that Wilkes suggested Macaulay was having an affair:

It is not only my opinion, but that of the generality of Mrs. Macaulay’s friends, that her head is affected, and some indiscretions with Dr. G—— are the common topic of conversation.Dr. James Graham had treated Macaulay’s headaches and other neurological symptoms, using her endorsement to build his career. Wilkes evidently thought their relationship went beyond doctor and patient. And of course he would know.

TOMORROW: Wilkes gives unabashed gossip a bad name.

Thursday, January 12, 2023

Catharine Macaulay “just returned from a Journey to Paris”

Today, after a gap of more than four months, I’m picking up the story of the British author Catharine Macaulay.

To catch us up, I’ll quote Macaulay’s own letter to the Earl of Buchan dated 23 Feb 1778:

Both Macaulay and Lord Buchan supported the American cause. France had just become a formal ally of the U.S. of A., and Macaulay wrote:

The author also told the earl: “I have this month published a vol of the history of England from the revolution to the resignation of Sir Robert Walpole.” That was the first volume of a never-completed set titled The History of England from the Revolution to the Present Time in a Series of Letters to a Friend. It was less formal than Macaulay’s earlier histories.

The “Friend” was the Rev. Dr. Thomas Wilson—Macaulay’s patron, host, and unrequited suitor in Bath. A portrait of Wilson with Macaulay’s daughter set me off on the author’s story last May. That daughter, Catherine Sophia, was “at a Boarding School at Chelsea” when her mother wrote to Lord Buchan; she would turn thirteen the next day.

TOMORROW: The Wilkesite view.

To catch us up, I’ll quote Macaulay’s own letter to the Earl of Buchan dated 23 Feb 1778:

The favor of your Lordship’s letter found me just returned from a Journey to Paris where I resided a few weeks for the recovery of my health after a long and dangerous illness.Macaulay had gained the strength to undertake that journey only after Dr. James Graham had provided her with “a judicious mixture of the Bark” to treat her “Billious intermitting Autumnal fever,” as I quoted here. The doctor’s sister Elizabeth Arnold was Macaulay’s traveling companion.

Both Macaulay and Lord Buchan supported the American cause. France had just become a formal ally of the U.S. of A., and Macaulay wrote:

I have the pleasure to inform your Lordship that sentiments of liberty which are as you observe lost in these united Kingdoms never flourished in a larger extent or with more vigorous animating force than they do at present in France.That reflected the Enlightenment circles that Macaulay visited since France was, after all, still a less democratic regime than Britain.

The author also told the earl: “I have this month published a vol of the history of England from the revolution to the resignation of Sir Robert Walpole.” That was the first volume of a never-completed set titled The History of England from the Revolution to the Present Time in a Series of Letters to a Friend. It was less formal than Macaulay’s earlier histories.

The “Friend” was the Rev. Dr. Thomas Wilson—Macaulay’s patron, host, and unrequited suitor in Bath. A portrait of Wilson with Macaulay’s daughter set me off on the author’s story last May. That daughter, Catherine Sophia, was “at a Boarding School at Chelsea” when her mother wrote to Lord Buchan; she would turn thirteen the next day.

TOMORROW: The Wilkesite view.

Wednesday, January 11, 2023

“She was surprised by the firing of the king’s troops”

Last month Alex Cain at Historical Nerdery rounded up four accounts from women who had all-too-close encounters with British troops during the Battle of Lexington and Concord.

Those are all stories preserved in the women’s own words, not questionable latter-day legends like Lydia Barnard.

Those accounts survive because:

Cain notes that the Rev. David McClure also wrote about seeing houses like Bradish’s along the battle road in Menotomy shot up with musket balls. Indeed, people can see the physical evidence of those shots in the Jason Russell House, as shown above.

But did the British muskets do all that damage? With a finite amount of ammunition, would the regulars have fired so many balls into a house with no one firing back from inside? Or might a lot of those bullets have come from provincial militiamen firing at the redcoats they saw around that house?

Those are all stories preserved in the women’s own words, not questionable latter-day legends like Lydia Barnard.

Those accounts survive because:

- Hannah Adams and Hannah Bradish described experiences that the Patriots could present to the world as atrocities, and therefore wrote down and spread around in 1775.

- Mary Hartwell and Anna Munroe lived long enough to be among the few people to remember 1775, making other people more interested in hearing and recording their stories.

about five o’clock on Wednesday last, afternoon, being in her bed-chamber, with her infant child, about eight days old, she was surprised by the firing of the king’s troops and our people, on their return from Concord. She being weak and unable to go out of her house, in order to secure herself and family, they all retired into the kitchen, in the back part of the house. She soon found the house surrounded with the king’s troops; that upon observation made, at least seventy bullets were shot into the front part of the house; several bullets lodged in the kitchen where she was, and one passed through an easy chair she had just gone from.After the battle, Bradish reported finding many things missing, “which, she verily believes, were taken out of the house by the king's troops.”

Cain notes that the Rev. David McClure also wrote about seeing houses like Bradish’s along the battle road in Menotomy shot up with musket balls. Indeed, people can see the physical evidence of those shots in the Jason Russell House, as shown above.

But did the British muskets do all that damage? With a finite amount of ammunition, would the regulars have fired so many balls into a house with no one firing back from inside? Or might a lot of those bullets have come from provincial militiamen firing at the redcoats they saw around that house?

Tuesday, January 10, 2023

Robert R. Livingston and the Brothels of New York

Last month, as part of a series of articles on members of Congress and slavery, the Washington Post published Gillian Brockell’s survey of artwork in the U.S. Capitol.

One passage that caught my eye was about the two sculptures New York has chosen to display:

But of course that wasn’t the detail that caught my eye—the reference to brothels did. That included a link to this article at the Gotham Center’s webpage about the Robert Livingston Papers, which says:

But here’s where the trail gets twisted. Page 484 of Gotham said:

Students at Columbia University used city records and newspaper reports to study the university’s connections to slavery. One section of that digital presentation is titled “Livingston Brothels: Columbia and Profits from Black Bodies.” That includes a “Timeline of Livingston Brothel Ownership” which states:

As for owning 154 Anthony Street in the 1820s, or 152 Anthony Street in the 1830s as a later panel says, Chancellor Livingston died in 1813. Perhaps this property was part of an unsettled estate, or there was another member of the family with a similar name (John had a son named Robert M. Livingston). But the Robert R. Livingston of the Continental Congress wasn’t around in the 1820s and 1830s when those properties were documented brothels.

Once again, Gilfoyle’s City of Eros and Wallace and Burrows’s Gotham don’t link Robert R. Livingston to buildings where prostitutes worked—they just say he was the older brother of John R. Livingston. There’s clear evidence that John owned and managed those properties, but that evidence dates from after Robert’s death. Furthermore, according to Gilfoyle, Robert tried to dissuade John from trading with Britain during the Revolutionary War, and John did it anyway, so we can hardly conclude the brothers always acted in concert. I welcome news of more recent findings that would change this picture, but I didn’t come across any.

Robert R. Livingston was undeniably a slaveholder. But as for him owning brothels, that idea appears to be a mistake. Robert’s historical celebrity seems to have drawn a couple of authoritative sources into blaming him for his younger brother’s activities.

One passage that caught my eye was about the two sculptures New York has chosen to display:

One is Declaration of Independence co-writer Robert R. Livingston, who came from a prominent slave-trading family and personally enslaved 15 people in 1790. He also owned brothels that housed Black women who may have been enslaved.Livingston (1746–1813, shown here) was on the committee of five Continental Congress delegates appointed to write the Declaration in May 1776. He participated in committee discussions but didn’t contribute memorably to the text, abstained from voting for independence along with the other New York delegates, and left the Congress before the formal signing.

But of course that wasn’t the detail that caught my eye—the reference to brothels did. That included a link to this article at the Gotham Center’s webpage about the Robert Livingston Papers, which says:

Along with members of his family, Livingston was also a slaveowner. According to the first federal census of 1790, he owned at least fifteen enslaved people. . . . By 1810 he owned at least five slaves. In addition, the Chancellor owned several brothels in lower Manhattan, which made have been homes for Black servants, or prostitutes.That looks like an authoritative source. The Gotham Center says it “was founded in 2000 by Mike Wallace, after his landmark work Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, co-authored with Edwin Burrows, won the Pulitzer.”

But here’s where the trail gets twisted. Page 484 of Gotham said:

One of the most enterprising de facto whoremasters was John R. Livingston, brother of the Chancellor (and steamboat financier) Robert Livingston. By 1828 he controlled at least five brothels near Paradise Square and a score more elsewhere in the city, with a tenant roster that included some of the best-known madams in New York. His involvement was well known, and when irate neighbors complained, he simply reshuffled the offending women to another of his buildings.Going back further in that book’s sources, Timothy J. Gilfoyle’s City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex, 1790-1920 (1992) laid out many details about John R. Livingston’s brothels. But Robert R. Livingston appears in that study only as John’s brother. Neither book states that Robert owned any brothels, even as part of a family concern.

Students at Columbia University used city records and newspaper reports to study the university’s connections to slavery. One section of that digital presentation is titled “Livingston Brothels: Columbia and Profits from Black Bodies.” That includes a “Timeline of Livingston Brothel Ownership” which states:

From 1820 - 1829 the Livingston family owned an astonishing number of properties on Anthony St; 26, 28, 30, 143, 147, 149, 154 Anthony St, and briefly 24, 30, 45, 140, 141, 142, 153, 155, and 157 Anthony St. John R Livingston owned the majority of these brothels, however, Robert R Livingston, one of Columbia’s most important founders, owned 154 Anthony St through this decade.I’m not sure what “one of Columbia’s most important founders” means here. Columbia was founded as King’s College in 1754, and Robert R. Livingston attended as an adolescent, graduating in 1765. He’s thus a Founder associated with Columbia, but he didn’t found Columbia. (His older cousin and successor in the Congress, Philip Livingston, was involved in setting up the college.)

As for owning 154 Anthony Street in the 1820s, or 152 Anthony Street in the 1830s as a later panel says, Chancellor Livingston died in 1813. Perhaps this property was part of an unsettled estate, or there was another member of the family with a similar name (John had a son named Robert M. Livingston). But the Robert R. Livingston of the Continental Congress wasn’t around in the 1820s and 1830s when those properties were documented brothels.

Once again, Gilfoyle’s City of Eros and Wallace and Burrows’s Gotham don’t link Robert R. Livingston to buildings where prostitutes worked—they just say he was the older brother of John R. Livingston. There’s clear evidence that John owned and managed those properties, but that evidence dates from after Robert’s death. Furthermore, according to Gilfoyle, Robert tried to dissuade John from trading with Britain during the Revolutionary War, and John did it anyway, so we can hardly conclude the brothers always acted in concert. I welcome news of more recent findings that would change this picture, but I didn’t come across any.

Robert R. Livingston was undeniably a slaveholder. But as for him owning brothels, that idea appears to be a mistake. Robert’s historical celebrity seems to have drawn a couple of authoritative sources into blaming him for his younger brother’s activities.

Monday, January 09, 2023

Boston Tea Party Online Panel Discussion, 10 Jan.