“The dissolution of a very delicate frame”

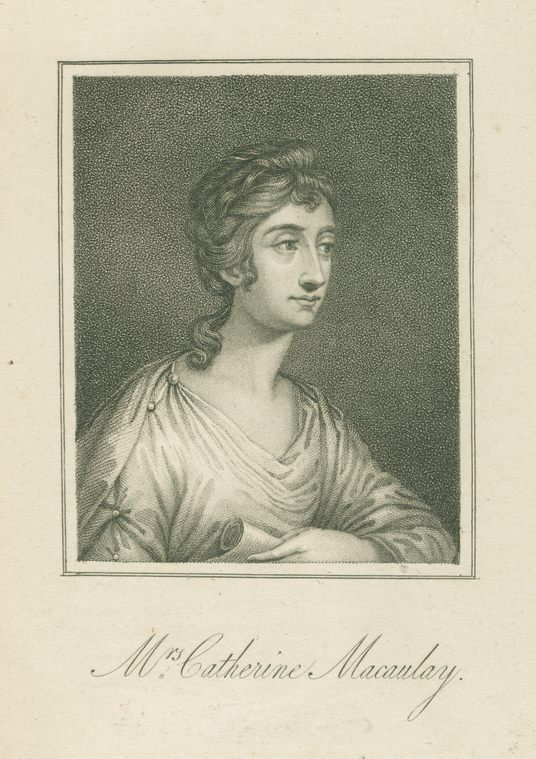

Catharine Macaulay wasn’t a well woman, and she wanted people to know it.

She began her first letter to John Adams, on 19 July 1771, with:

[I must note that Macaulay appears in Founders Online indexed under four separate names: Catharine Macaulay, Catherine Macaulay, Catharine Sawbridge Macaulay, and Catharine Sawbridge Macaulay Graham. No one click brings up all the letters to and from her. Linking those seems like a quick and useful digital humanities project.]

As I quoted here, in late 1776 the historian asked Dr. James Graham to treat her. Early the next year she offered a public testimonial to his experimental methods:

In February 1778 Macaulay told the Earl of Buchan:

TOMORROW: A doctor’s wife.

She began her first letter to John Adams, on 19 July 1771, with:

A very laborious attention to the finishing the fifth vol of my history of England with a severe fever of five months duration the consequence of that attention has hitherto deprived me of the opportunity of answering your very polite letter…And she quickly returned to that theme: “I am really very much concerned to hear that you labor under the heavy misfortune of a weak and infirm state of health. I simpathise with you in body and mind having rarely any alternative from either labor or pain.”

[I must note that Macaulay appears in Founders Online indexed under four separate names: Catharine Macaulay, Catherine Macaulay, Catharine Sawbridge Macaulay, and Catharine Sawbridge Macaulay Graham. No one click brings up all the letters to and from her. Linking those seems like a quick and useful digital humanities project.]

As I quoted here, in late 1776 the historian asked Dr. James Graham to treat her. Early the next year she offered a public testimonial to his experimental methods:

I have the happiness to declare, that a great part of my disease immediately gave way to your Chemical Essences, your Ætherial, Magnetic, and Electric Applications; the pains in my ears and throat subsided, the fevers and irritations of my nerves left me, and my spirits were sufficiently invigorated to break from a confinement of six weeks, and to exercise in the open air.In the summer of 1777, however, Macaulay’s health took a bad turn. She later told the new Earl of Harcourt:

By the accident of going into a tepid bath rather too cool and after a hot day, I was attacked, my Lord, at the end of the summer with one of the most formidable of all the species of intermittent fevers, and every symtom which could threaten the dissolution of a very delicate frame.But Macaulay was in no shape to travel to the south of France. Fortunately, Dr. Graham hurried back from his wife and children in Edinburgh to his celebrated patient in Bath.

The [medical] faculty here, after having made what was very bad much worse by their unavailing remedies, in despair of my life, and not caring that I should dye under their hands, sent me over to Nice for change of air.

In February 1778 Macaulay told the Earl of Buchan:

I must do Dr Graham the justice to observe to your Lordship that he not only strengthened and returned the injured state of my nerves, injured greatly by a long and severe application, but when on his return from Edinburgh he found me on the brink of the grave from the severe attack of a Billious intermitting Autumnal fever he under God gave me a rescue from the Grim Tyrant by a judicious mixture of the Bark,Macaulay started to feel strong enough to consider that trip to France. Dr. Graham evidently seconded his colleagues’ recommendation. But the historian’s health was still shaky enough that she needed a traveling companion, preferably a genteel lady like herself.

often I had repeatedly taken that Drug not only without success but with very ill effects when administered by others of the faculty, I do assure your Lordship I look upon Dr Graham as a happy Genius in the medical line of knowledge…

TOMORROW: A doctor’s wife.

No comments:

Post a Comment