The Details in the Devil

For the Washington Post, University of Delaware history professor Zara Anishanslin wrote about the roots of far-right accusations that the Devil is involved in American politics reach down deep to the Revolutionary protest movement.

Devils were a crucial element of American protests against the Stamp Act, including the August 1765 effigies hanging from what became Liberty Tree, the subsequent processions modeled on that event in other colonies, and even Isaiah Thomas’s little stamps on the Halifax Gazette.

I’d push that form of politics back even further because the Stamp Act protest borrowed imagery from New England Pope Nights, which always included the Devil and multiple imps. Since that holiday was part of the British Empire’s loud stance against Roman Catholicism and the Stuart claimants to the throne, using a religious figure of evil made sense.

And Pope Night was always political as well. The Stuart claimants were contemporary figures, and Charles Edward Stuart almost came within striking distance of the British throne in 1745. A 1750s Pope Night was recalled as lambasting Adm. John Byng, another contemporaneous villain. So the shift to using Pope Night–like effigies against men associated with the Stamp Act wasn’t all that big.

Likewise, after Benedict Arnold defected in 1780, Americans resurrected the Pope Night imagery, largely suppressed while leaders sought alliances with the Québecois and French, to show their enmity to him. The details might change, but the Devil did not.

Anishanslin also writes:

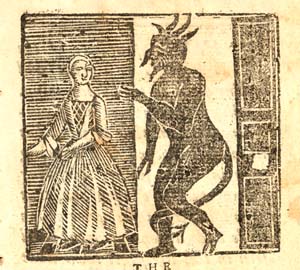

In contrast, woodcuts like the one above usually did show the devil as almost a black silhouette. Often that silhouette had a tail, long pointed nose, and spiky horns or hair—different from how artists of the time showed a generic “Black man.” While the symbolism of blackness itself in British-American culture can’t be denied, I don’t think British-American artists were depicting the Devil in the form of either a man or an African.

Devils were a crucial element of American protests against the Stamp Act, including the August 1765 effigies hanging from what became Liberty Tree, the subsequent processions modeled on that event in other colonies, and even Isaiah Thomas’s little stamps on the Halifax Gazette.

I’d push that form of politics back even further because the Stamp Act protest borrowed imagery from New England Pope Nights, which always included the Devil and multiple imps. Since that holiday was part of the British Empire’s loud stance against Roman Catholicism and the Stuart claimants to the throne, using a religious figure of evil made sense.

And Pope Night was always political as well. The Stuart claimants were contemporary figures, and Charles Edward Stuart almost came within striking distance of the British throne in 1745. A 1750s Pope Night was recalled as lambasting Adm. John Byng, another contemporaneous villain. So the shift to using Pope Night–like effigies against men associated with the Stamp Act wasn’t all that big.

Likewise, after Benedict Arnold defected in 1780, Americans resurrected the Pope Night imagery, largely suppressed while leaders sought alliances with the Québecois and French, to show their enmity to him. The details might change, but the Devil did not.

Anishanslin also writes:

How the devil looked was important. And in Colonial and revolutionary era America, the devil was often portrayed as a Black man. Illustrations of the devil in Cotton Mather’s account of the Salem Witch Trials and Paul Revere’s prints alike both showed the devil with black skin. Such depictions played into the racism and fear of slave revolt that undergirded much of the revolution.That made me take a closer look at figures of the devil in American printing. The first thing I noticed is a difference between the depictions in woodcuts and in more expensive engravings, such as Revere’s “A Warm Place—Hell.” Engravings could show more detail, but they couldn’t depict solid black. The devils and demons on those pages tend to look like dark, hairy monsters.

In contrast, woodcuts like the one above usually did show the devil as almost a black silhouette. Often that silhouette had a tail, long pointed nose, and spiky horns or hair—different from how artists of the time showed a generic “Black man.” While the symbolism of blackness itself in British-American culture can’t be denied, I don’t think British-American artists were depicting the Devil in the form of either a man or an African.

1 comment:

When HP Lovecraft depicted the Black Man of colonial lore in Dreams in the Witch House, he described him as white man with solid black skin. Given HPL's notorious racism, it seems reasonable to assume that if he thought the Black Man was supposed to be African, he would have described him as such.

This aligns with your last paragraph.

Post a Comment