Bernard reported to his superior in London, Secretary of State Hillsborough:

I went early to the Council to watch the Proceedings of the House, having been informed that they intended to originate an Invitation for another Congress [like the Stamp Act Congress]: In which Case the Moment I got Intelligence of it I intended to dissolve them.The representatives actually started the day with a few housekeeping items, certifying financial accounts and putting off petitions to a future session—preparing for the body to be dissolved. Only then did they turn to the royal government’s demand that they rescind the Circular Letter.

The House kept themselves locked up all the Morning; the best Part of which was spent in preparing a Letter to your Lordship which I am told is very lengthy: but as I have not seen it and probably shall not be allowed a Sight of it ’till it is printed in the Newspapers, I will say no more of it than that I am told it is in the old Strain, complaining that they have been misrepresented; tho’ the present Censure arises from an Act of theirs which they have had circulated throughout his Majesty’s Dominions:

The House cleared the gallery of spectators, informed the Council they were going into debate, and told the doorkeeper not to call out any members or bring in any messages. A committee led by Samuel Adams and James Otis, Jr., presented the drafts of replies to the governor and Secretary of State.

The letter to Bernard is four pages long in the legislative record. The letter to Hillsborough, written for the signature of speaker of the house Thomas Cushing, is five and a half pages. Clearly those documents had been in the works for days as the House handled other business and stalled for time.

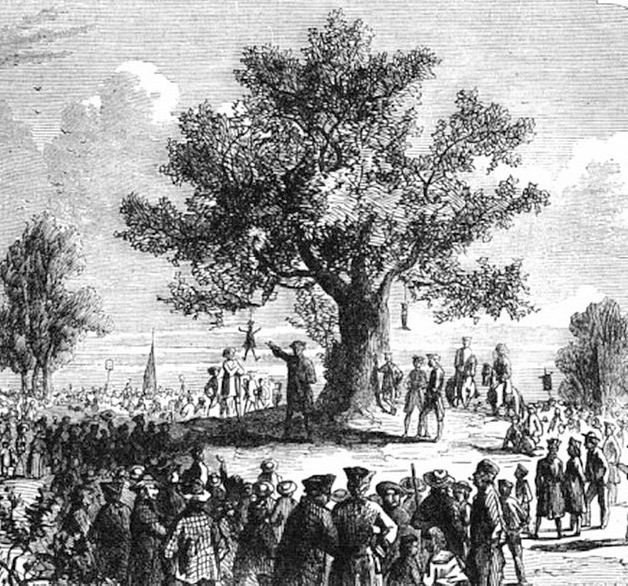

After the letter to Hillsborough was read twice, and perhaps tweaked, the legislators voted 92–13 to accept it. Then the House was asked whether it would rescind the Circular Letter, as London had ordered. Again, 92 representatives defied the royal orders, and only 17 voted to rescind. This was one of the rare “roll call votes” in the colonial House with every legislator’s choice recorded and published.

Bernard complained, “among the Majority were many Members who were scarce ever known upon any other Occasion to vote against the Government Side of a Question; so greatly has infatuation and intimidation gained Ground.” Clearly legislators thought that defiance would be popular with voters.

And the House wasn’t done. It then appointed Adams, Otis, Jerathmeel Bowers, Col. James Otis, and John Hancock to draft a petition “praying that His Majesty would be graciously pleased to remove his Excellency Francis Bernard, Esq; from the Government of this Province.” The vote on that motion was not recorded, and Bernard said it “was carried by a Majority of 5” only. But what a surprise! Adams had a two-page draft of that petition ready to go.

Rather than immediately dissolve the legislature, Gov. Bernard decided to wait until he had officially received the House’s response. He felt confident that this new committee wouldn’t be able “to cook up something” to present as an impeachable offense. Indeed, after some debate the House asked Adams and colleagues to “bring in the Evidence in Support” of their charges.

In late afternoon, Bernard sent a message to the House members to meet him in the Council chamber with their official answer to his demand. But even then there was a surprise. The night before, the Council had the named its own “Committee to consider the State of the Province,” including Whigs James Bowdoin, William Brattle, and Royall Tyler and government supporters Thomas Flucker and James Russell. That committee wanted to read their own petition to the king. Bernard wanted to go straight to shutting down the House. He reported the resulting dispute:

as soon as the House entered one of the Committee of the Council expostulated with me upon my calling up the House while the Council was proceeding on the Address and was so indecent as to appeal to the House. I silenced him: another Gentleman interposed; I stopt him also, and proceeded to the Prorogation.The governor informed the assembled legislators which of the bills approved by both chambers of the General Court in the legislative session he had approved. Then secretary Andrew Oliver announced that Gov. Bernard prorogued the House, sending all the representatives home.

The conflict over the Circular Letter was officially over. The House had refused to retract it, and the governor had followed the orders from London to dissolve the body. Protests and petitions about the Townshend Act went on. But now the Massachusetts Whigs had a new grievance, and a new triumph. Soon Paul Revere engraved on the Sons of Liberty Bowl:

To the Memory of the glorious NINETY-TWO: Members

of the Honbl. House of Representatives of the Massachusetts-Bay

who, undaunted by the insolent Menaces of Villains in Power,

from a Strict Regard to Conscience, and the LIBERTIES

of their Constituents, on the 30th. of June 1768

Voted NOT TO RESCIND.