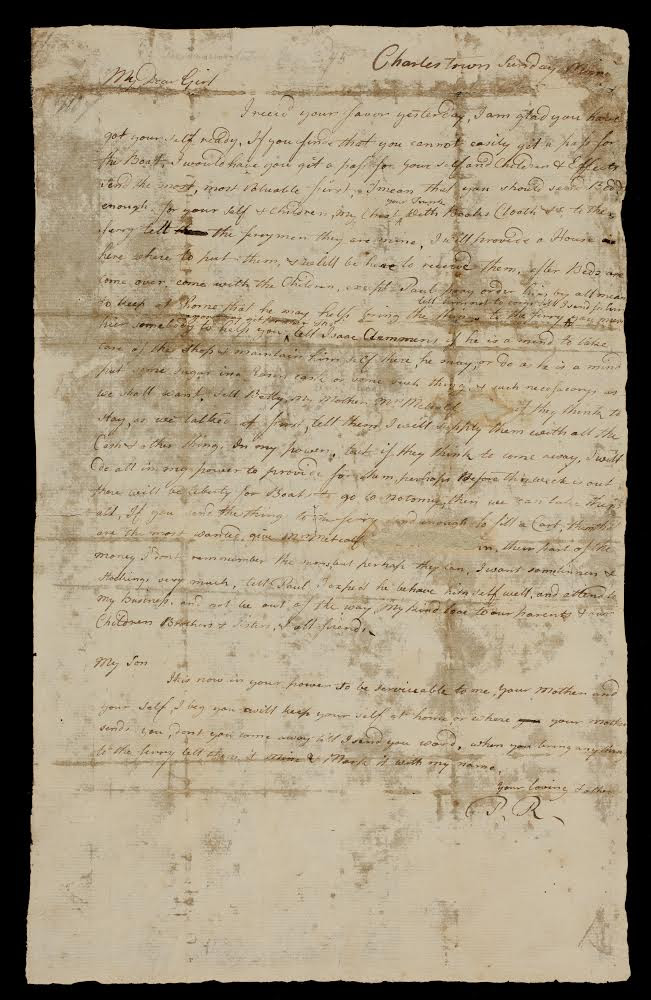

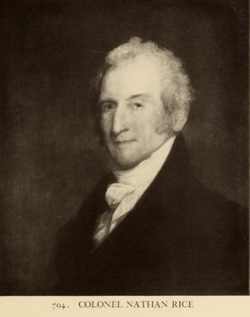

Shortly after the Siege of Boston began in the spring of 1775, Paul Revere took a few minutes to scrawl a hasty letter to his wife, Rachel. In it, he included details of his plan to get most of the Revere family out of occupied Boston.The letter is datelined only “Charlestown Sunday [Morn?].” Context indicates the silversmth wrote it on 23 or, more likely, 30 Apr 1775.

In 2011, a Revere descendant brought the document to the Paul Revere House, and three years later the museum acquired it.

The Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia told a similar story this summer:

Discovered in a shoebox in a Northern California garage, the long-lost Revolutionary War diary of John Claypoole is now on display at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. Claypoole was the third husband of Betsy Ross, the seamstress and upholsterer who has long been celebrated by many as the creator of the first American flag.At the time, Claypoole and Ross’s second husband, Joseph Ashburn, were in the Old Mill Prison in Plymouth, England, after being captured on American privateers. Ashburn died as a prisoner. Claypoole survived, brought the sad news to the widow, and then married her.

Claypoole’s handwritten diary, which includes letters and songs he transcribed, was written during the years 1781 and 1782…

Those documents have something in common besides being connected to middling-class craftspeople who lived through the Revolution and became household names in America’s Colonial Revival. Both were transcribed and published in the nineteenth century.

Elbridge H. Goss published the Revere letter in his 1891 biography, reporting the original as still being in the family. But within a generation scholars didn’t know where it was. They had to rely on Goss’s transcription.

Likewise, the Claypoole prison diary was published in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography in 1892 but then dropped out of sight until a descendant found it among her late mother’s family papers.

For both documents, scholars already had access to the texts. So where is the value in having the originals? Of course, it’s good to be able to confirm that a transcribed document actually exists, and that the published transcription is accurate and complete. There might be additional information (Goss didn’t publish the “Charlestown Sunday” line), perhaps in non-textual form (What size of notebook could a prisoner of war keep?).

But we also have to acknowledge that the authenticity and antiquity of a historical document produces a magnetic appeal that goes beyond the information it preserves. Though they might be most useful to historians as data repositories, they’re also relics of the past.