At the end of November 1773, the ship Dartmouth was moored in Boston’s inner harbor, watched by a militia-style patrol of volunteers to ensure the tea it carried was not unloaded and taxed.

The Rotch family’s vessel, under the command of James Hall, brought other cargo as well. Among those items were copies of Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.

Wheatley had recently become legally free, and she was counting on sales of those books for her income.

Fortunately, by 1 December the local Whigs made clear that everything could be unloaded from the Dartmouth except the East India Company tea, so the books came ashore.

Historians only recently recognized the connection between Wheatley’s book and the Boston Tea Party because no one mentioned it at the time. Wheatley may have been worried 250 years ago today, but by the time she was writing the letters that survive she had her books on dry land and was busy promoting orders.

Wheatley wrote that her books would arrive “in Capt. Hall,” using the common way of referring to a ship by its master rather than its name. About ten years ago Wheatley biographer Vincent Carretta, researcher Richard Kigel, and others realized that the captain of that name arriving in Boston around that time had to be James Hall on the Dartmouth.

The sestercentennial of the Tea Party thus coincides with the sestercentennial of the publication of Phillis Wheatley’s book in America, and both events are being commemorated this season.

Ada Solanke’s play Phillis in Boston will have its last performances for the year in Old South Meeting House, the poet’s own church, on Sunday, 3 December. That site-specific drama depicts the poet, her friend Obour Tanner, her husband-to-be John Peters, her recent owner Susannah Wheatley, and abolitionist Prince Hall. Order tickets here.

The next evening, 4 December, the Boston Public Library will host “Faces of Phillis,” a free program discussing the poet from various perspectives. It will start with a staged reading of parts of Solanke’s plays about Wheatley. Then there will be a panel featuring Solanke, sculptor Meredith Bergmann, and Kyera Singleton of the Royall House & Slave Quarters museum. The evening will conclude with Boston’s Poet Laureate, Porsha Olayiwola, performing a dramatic reading of her own work and one of Wheatley’s poems.

“Faces of Phillis” is scheduled to last from 6:00 to 7:30 P.M. Register for that event here.

History, analysis, and unabashed gossip about the start of the American Revolution in New England.

▼

Thursday, November 30, 2023

Wednesday, November 29, 2023

The Lexington Tea-Burning, in 1773 and 2023

As I recounted yesterday, on 13 Dec 1773 a town meeting in Lexington voted unanimously to resist the Tea Act, pledge not to help unload any East India Company tea, and condemn the consignees who were trying to import that tea.

That was the easy part. None of the people at the meeting were consignees, or Boston waterfront workers.

Then someone proposed a further measure: Any head of household in Lexington who would “Use or consume any Tea in their Famelies” should be treated with Neglect & Contempt.”

Even though all tea in town was by definition not imported under the Tea Act. Even though that tea might not even have been subject to the Townshend duties (if it had been smuggled in from Dutch islands).

No tea at all. As a gesture of solidarity with the people in Boston trying to stop the new tea cargoes from being landed, and a protest against Parliament’s revenue acts in general. Talk about giving up caffeine!

As I said before, Lexington was a strongly Whiggish community. We can see that in the fact that the meeting actually went through with this proposal, approving it without recorded dissent.

Furthermore, on 16 Dec 1773, Isaiah Thomas’s Massachusetts Spy reported:

About a decade ago, Lexington began to reenact that tea-burning each year a few days before the Boston Tea Party commemoration. The town will have a sestercentennial reenactment on Sunday, 10 December, in and around Buckman Tavern, which faces the common and the site of the meetinghouse where the events of 1773 took place.

The schedule of events:

That was the easy part. None of the people at the meeting were consignees, or Boston waterfront workers.

Then someone proposed a further measure: Any head of household in Lexington who would “Use or consume any Tea in their Famelies” should be treated with Neglect & Contempt.”

Even though all tea in town was by definition not imported under the Tea Act. Even though that tea might not even have been subject to the Townshend duties (if it had been smuggled in from Dutch islands).

No tea at all. As a gesture of solidarity with the people in Boston trying to stop the new tea cargoes from being landed, and a protest against Parliament’s revenue acts in general. Talk about giving up caffeine!

As I said before, Lexington was a strongly Whiggish community. We can see that in the fact that the meeting actually went through with this proposal, approving it without recorded dissent.

Furthermore, on 16 Dec 1773, Isaiah Thomas’s Massachusetts Spy reported:

We are positively informed that the patriotic inhabitants of Lexington, at a late meeting, unanimously resolved against the use of Bohea Tea of all sorts, Dutch or English importation; and to manifest the sincerity of their resolution, they bro’t together every ounce contained in the town, and committed it to one common bonfire.As it turned out, Charlestown took longer to act (I’ll get to that story). When the Boston Gazette and Boston Post-Boy (newspapers on opposite political sides) reprinted the item days later, they left out that last sentence.

We are also informed, Charlestown is in motion to follow their illustrious example.

About a decade ago, Lexington began to reenact that tea-burning each year a few days before the Boston Tea Party commemoration. The town will have a sestercentennial reenactment on Sunday, 10 December, in and around Buckman Tavern, which faces the common and the site of the meetinghouse where the events of 1773 took place.

The schedule of events:

- 9:30 A.M. – 4:00 P.M.: Pop-up exhibit on historic hot drinks upstairs at Buckman Tavern

- 12:00 noon – 3:00 P.M.: Drop-in activities upstairs at Buckman Tavern

- 12:30 P.M.: The Lexington Minute Men practice military drill

- 1:00: 18th-century townspeople (and local Boy Scouts) begin to build a fire

- 1:20 – 2:00: Music from the William Diamond Jr. Fife and Drum Corps and the Lexington Historical Society Colonial Singers

- 1:30: THE BURNING OF THE TEA

- 2:00: Concluding musket salute from the Lexington Minute Men

Tuesday, November 28, 2023

Lexington and the “subtle, wicked ministerial plan”

Last week I analyzed the accounts of tea burning in Marshfield 250 years ago and concluded that I found no strong evidence for the exact date of this event.

Marshfield was notable for being split between Whigs and Loyalists. It had an Anglican church as well as the Congregationalists. The control of town meeting teetered back and forth between factions. The tea-burning, whenever it happened, wasn’t an official act.

In contrast, the town of Lexington was militantly Whig. Its minister, the Rev. Jonas Clarke, supported that stance. Early on, the town voted to create a committee of correspondence to share news and views with Boston and elsewhere—a litmus test for radicalism.

On 13 Dec 1773, as the crisis over the East India Company cargoes in Boston heated up, Lexington called a town meeting. Charles Hudson’s town histories published the record, and Alexander Cain, author of We Stood Our Ground: Lexington in the First Year of the American Revolution, has shared more exact transcriptions at Untapped History. I drew the quotations that follow from a combination of those sources.

Lexington’s committee of correspondence produced a blistering statement about the Tea Act:

After the meeting unanimously approved those statements, someone proposed another:

TOMORROW: What happened next.

Marshfield was notable for being split between Whigs and Loyalists. It had an Anglican church as well as the Congregationalists. The control of town meeting teetered back and forth between factions. The tea-burning, whenever it happened, wasn’t an official act.

In contrast, the town of Lexington was militantly Whig. Its minister, the Rev. Jonas Clarke, supported that stance. Early on, the town voted to create a committee of correspondence to share news and views with Boston and elsewhere—a litmus test for radicalism.

On 13 Dec 1773, as the crisis over the East India Company cargoes in Boston heated up, Lexington called a town meeting. Charles Hudson’s town histories published the record, and Alexander Cain, author of We Stood Our Ground: Lexington in the First Year of the American Revolution, has shared more exact transcriptions at Untapped History. I drew the quotations that follow from a combination of those sources.

Lexington’s committee of correspondence produced a blistering statement about the Tea Act:

…the Enemies of the Rights & Liberties of Americans, greatly disappointed in the Success of the Revenue Act, are seeking to Avail themselves of New, & if possible, Yet more detestable Measures to distress, Enslave & destroy us.The committee proposed six resolves to steer the town away from this horrible fate. These included:

Not enough that a Tax was laid Upon Teas, which should be Imported by Us, for the Sole Purpose of Raising a revenue to support Taskmasters, Pensioners, &c., in Idleness and Luxury; But by a late Act of Parliament, to Appease the wrath of the East India Company, whose Trade to America had been greatly clogged by the operation of the Revenue Acts, Provision is made for said Company to export their teas to America free and discharged from all Duties and Customs in England, but liable to all the same Rules, Regulations, Penalties & Forfeitures in America, as are Provided by the Revenue Act. . . .

Once admit this subtle, wicked ministerial plan to take place, once permit this tea, thus imposed upon us by the East India Company, to be landed, received, and vended by their consignees, factors, &c., the badge of our slavery is fixed, the foundation of ruin is surely laid; and, unless a wise and powerful God, by some unforeseen revolution in Providence, shall prevent, we shall soon be obliged to bid farewell to the once flourishing trade of America, and an everlasting adieu to those glorious rights and liberties for which our worthy ancestors so earnestly prayed, so bravely fought, so freely bled!

2. That we will not be concerned either directly or indirectly in landing, receiving, buying, or selling, or even using any of the Teas sent out by the East India Company, or that shall be imported subject to a duty imposed by Act of Parliament, for the purpose of raising a revenue in America.Other resolves endorsed everything the Bostonians were doing and condemned the tea consignees, even naming Richard Clarke and the Hutchinson brothers.

3. That all such persons as shall directly or indirectly aid and assist in landing, receiving, buying, selling, or using the Teas sent by the East India Company, or imported by others subject to a duty, for the purpose of a revenue, shall be deemed and treated by us as enemies of their country.

After the meeting unanimously approved those statements, someone proposed another:

That if any Head of a Family in this Town, or any Person, shall from this time forward; & until the Duty taken off, purchase any Tea, Use or consume any Tea in their Famelies, such person shall be looked upon as an Enemy to this town & to this Country, and shall by this Town be treated with Neglect & Contempt.Now they were getting personal.

TOMORROW: What happened next.

Monday, November 27, 2023

“Liberty or Death: Boston Tea Party” Now Streaming

A few months back, an invitation came to me through Revolution 250. Was I up for answering questions about the Boston Tea Party for a television show?

I said yes, trimmed my beard, put on a blazer, and showed up at History Cambridge as directed. The local production crew there was very nice, as was the producer asking the questions via a feed from New York.

Later I found out the program would be on Fox Nation, a subscription service. And only this past week did I learn that it’s titled Liberty or Death: Boston Tea Party and features Rob Lowe as the host and main narrator.

Hey, if I'd known that this production would be so star-studded, I might have asked for twice the money. (Really, I did this as a volunteer for Revolution 250.)

Liberty or Death: Boston Tea Party combines dramatized scenes with talking-heads interviews. It comes in four episodes, each about half an hour long. Here’s the trailer. To watch the whole thing this fall, one has to subscribe to Fox Nation.

I’m confident about the accuracy of what Benjamin L. Carp, Robert J. Allison, Hannah Farber, and any other historians on screen have said. I’m reasonably sure I didn’t embarrass myself with misstatements.

I can’t promise anything about the dramatized scenes or narration since we didn't see a script. And I have little doubt that if one of us talking heads said something that contradicted a dramatic scene, the interview would have been trimmed, not that footage. That’s show biz.

Ben Carp points out that since we appear in a show with Rob Lowe, we are now just three degrees of separation away from Kevin Bacon.

(Thanks to Adam Hodges, Ben Carp, and Bob Allison for alerting me that this show was now streaming away and that I wasn’t jettisoned before the final cut.)

I said yes, trimmed my beard, put on a blazer, and showed up at History Cambridge as directed. The local production crew there was very nice, as was the producer asking the questions via a feed from New York.

Later I found out the program would be on Fox Nation, a subscription service. And only this past week did I learn that it’s titled Liberty or Death: Boston Tea Party and features Rob Lowe as the host and main narrator.

Hey, if I'd known that this production would be so star-studded, I might have asked for twice the money. (Really, I did this as a volunteer for Revolution 250.)

Liberty or Death: Boston Tea Party combines dramatized scenes with talking-heads interviews. It comes in four episodes, each about half an hour long. Here’s the trailer. To watch the whole thing this fall, one has to subscribe to Fox Nation.

I’m confident about the accuracy of what Benjamin L. Carp, Robert J. Allison, Hannah Farber, and any other historians on screen have said. I’m reasonably sure I didn’t embarrass myself with misstatements.

I can’t promise anything about the dramatized scenes or narration since we didn't see a script. And I have little doubt that if one of us talking heads said something that contradicted a dramatic scene, the interview would have been trimmed, not that footage. That’s show biz.

Ben Carp points out that since we appear in a show with Rob Lowe, we are now just three degrees of separation away from Kevin Bacon.

(Thanks to Adam Hodges, Ben Carp, and Bob Allison for alerting me that this show was now streaming away and that I wasn’t jettisoned before the final cut.)

Sunday, November 26, 2023

Summing Up the Evidence on the Marshfield Tea Burning

Last week, inspired by today’s reenactment of the tea burning in Marshfield, I traced all the sources I could find about that event.

I found no contemporaneous or first-person account. The earliest description appeared in an 1854, and more details dribbled out over the next century and beyond, based on either family lore or no stated authority at all.

Hazy as that local tradition is, I nonetheless believe that people in Marshfield did burn tea in the wake of the Boston Tea Party.

The 1854 story echoes what happened in other Massachusetts communities, such as Salem, Lexington, and Newburyport.

First, the community agreed unofficially not to drink or sell tea to show their opposition to the Tea Act (not because the retail price of tea was too high). Local Whig leaders confiscated that form of property from shops and locked it up. Then something spurred younger, more radical Whigs to take the tea and make a show of burning it.

The 1854 report said Nehemiah Thomas confiscated the tea, and contemporaneous documents show he was indeed the town’s senior Whig, clerk, treasurer, and deacon. But that report also said he wasn’t in town for the burning.

Instead, late in the nineteenth century authors attached two brothers-in-law to the story: Jeremiah Low, who would have descendants in Marshfield, and Benjamin White, also documented as a Whig activist in this period. Plus other, unnamed citizens.

In the twentieth century local historians pointed to a very old building as one of the places the tea was stored. That’s plausible; in the 1770s the building was an ordinary, or tavern, and towns did use public houses for public business. That said, there might have been appeal in linking this rare surviving building to a historic event, providing a focus for commemoration. So I’m a little less convinced about that claim.

I’m still left puzzling about some details of this event, however. Here are my unanswered questions.

A. Starting with a history of the White family in 1895, authors describe Marshfield’s Tea Rock as “flat on ye top,” “flatt on ye top,” and “upon a stone quite flat on top”—all of those phrases within quotation marks. That implies they were quoting from a source. But none of those authors explains where those words come from, and a Google Books search turns up nothing. Is there a missing source?

B. In 1929 the Boston Herald said that after setting fire to the tea Jeremiah Low “was later forced to flee to New York with his family.” While not making an explicit connection, that article and local authors who repeated the information implied that the Lows had to leave town because of their Whig activity.

Whoever wrote that article certainly got some information from Low’s descendants. The reporter also wrote that “a fourth generation descendant of Jeremiah” was Seth Low [1850–1916], president of Columbia University and a reform mayor of New York.

However, L. E. Fredman’s article on Mayor Low in the Journal of American Studies in 1972 and online genealogies say the man was descended from a Low family in Ipswich and Salem, not Marshfield.

Furthermore, for most of the decade after 1773 Marshfield was a safe place for Whigs while New York was where Loyalists found refuge. So what was the real basis of this family lore? What had been lost or added?

C. What was the source for Cynthia Hagar Krusell’s statement in Of Tea and Tories (1976) that the Marshfield tea-burning occurred on the night of 19 Dec 1773? Was that just the first Sunday after the Boston Tea Party? If the event occurred when Nehemiah Thomas was out of town on some legislative business, as late-1800s sources suggest, that would have been late 1774 or afterward.

I found no contemporaneous or first-person account. The earliest description appeared in an 1854, and more details dribbled out over the next century and beyond, based on either family lore or no stated authority at all.

Hazy as that local tradition is, I nonetheless believe that people in Marshfield did burn tea in the wake of the Boston Tea Party.

The 1854 story echoes what happened in other Massachusetts communities, such as Salem, Lexington, and Newburyport.

First, the community agreed unofficially not to drink or sell tea to show their opposition to the Tea Act (not because the retail price of tea was too high). Local Whig leaders confiscated that form of property from shops and locked it up. Then something spurred younger, more radical Whigs to take the tea and make a show of burning it.

The 1854 report said Nehemiah Thomas confiscated the tea, and contemporaneous documents show he was indeed the town’s senior Whig, clerk, treasurer, and deacon. But that report also said he wasn’t in town for the burning.

Instead, late in the nineteenth century authors attached two brothers-in-law to the story: Jeremiah Low, who would have descendants in Marshfield, and Benjamin White, also documented as a Whig activist in this period. Plus other, unnamed citizens.

In the twentieth century local historians pointed to a very old building as one of the places the tea was stored. That’s plausible; in the 1770s the building was an ordinary, or tavern, and towns did use public houses for public business. That said, there might have been appeal in linking this rare surviving building to a historic event, providing a focus for commemoration. So I’m a little less convinced about that claim.

I’m still left puzzling about some details of this event, however. Here are my unanswered questions.

A. Starting with a history of the White family in 1895, authors describe Marshfield’s Tea Rock as “flat on ye top,” “flatt on ye top,” and “upon a stone quite flat on top”—all of those phrases within quotation marks. That implies they were quoting from a source. But none of those authors explains where those words come from, and a Google Books search turns up nothing. Is there a missing source?

B. In 1929 the Boston Herald said that after setting fire to the tea Jeremiah Low “was later forced to flee to New York with his family.” While not making an explicit connection, that article and local authors who repeated the information implied that the Lows had to leave town because of their Whig activity.

Whoever wrote that article certainly got some information from Low’s descendants. The reporter also wrote that “a fourth generation descendant of Jeremiah” was Seth Low [1850–1916], president of Columbia University and a reform mayor of New York.

However, L. E. Fredman’s article on Mayor Low in the Journal of American Studies in 1972 and online genealogies say the man was descended from a Low family in Ipswich and Salem, not Marshfield.

Furthermore, for most of the decade after 1773 Marshfield was a safe place for Whigs while New York was where Loyalists found refuge. So what was the real basis of this family lore? What had been lost or added?

C. What was the source for Cynthia Hagar Krusell’s statement in Of Tea and Tories (1976) that the Marshfield tea-burning occurred on the night of 19 Dec 1773? Was that just the first Sunday after the Boston Tea Party? If the event occurred when Nehemiah Thomas was out of town on some legislative business, as late-1800s sources suggest, that would have been late 1774 or afterward.

Saturday, November 25, 2023

“And all servile Labour is forbidden”

Thursday, 25 Nov 1773, 250 years ago today, was a holiday in Massachusetts.

About a month earlier, Thomas Hutchinson had issued this proclamation, printed on broadsides as shown at University Archives auction house:

In 1773, between the governor’s proclamation and Thanksgiving Day there had been two small riots over tea, Hutchinson’s sons and the other consignees were keeping low profiles, and everyone was on tenterhooks waiting for the first East India Company cargo to arrive.

According to merchant John Rowe, that Thanksgiving saw “Dull heavy Raw Weather.”

About a month earlier, Thomas Hutchinson had issued this proclamation, printed on broadsides as shown at University Archives auction house:

Massachusetts-Bay. }New Englanders expected to observe some autumn Thursday as a Thanksgiving, with sermons in the daytime and a big family dinner. However, the date of that holiday wasn’t set by the governors until the fall.

By the Governor.

A PROCLAMATION for a Publick Thanksgiving.

Whereas it is our incumbent Duty to make our frequent publick thankful Acknowledgement to Almighty GOD our great Benefactor, as well for the Mercies of his common Providence as for the distinguishing Favours which at any Time he may see meet to confer upon us:

AND WHEREAS among many other Instances of the Favour of Heaven towards us of a publick Nature in the Course of the Year past, it hath pleased God to continue the Life of our Sovereign Lord King GEORGE—of our most Gracious Queen CHARLOTTE and of the rest of the Royal Family—to succeed His Majesty’s Councils and Endeavours for Preserving Peace to the British Dominions—to continue to us a good Measure of Health—to prosper our Husbandry, Merchandize, and Fishery:

I HAVE therefore thought fit to appoint, and I do, with the Advice of His Majesty’s Council, appoint Thursday the Twenty-fifth Day of November next to be a Day of Publick Thanksgiving throughout the Province, exhorting and requiring the several Societies for Religious Worship to assemble on that Day, and to offer up their devout Praises to GOD for the several Mercies aforementioned, and for all other Favours which He hath been graciously pleased to bestow upon us, accompanying their Thanksgivings with fervent Prayers that, after they shall have sang the Praises of God, they may not forget his Works.

And all servile Labour is forbidden on the said Day.

GIVEN at the Council-Chamber in Boston, the Twenty-eighth Day of October, in the Fourteenth Year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord GEORGE the Third, by the Grace of GOD, of Great-Britain, France, and Ireland, KING, Defender of the Faith, &c. Annoq; Domini, 1773.

By His Excellency's Command,

Tho’s Flucker, Secr’y.

T. Hutchinson.

GOD Save the KING.

BOSTON: Printed by RICHARD DRAPER, Printer to His Excellency the Governor, and the Honorable His Majesty’s Council. 1773.

In 1773, between the governor’s proclamation and Thanksgiving Day there had been two small riots over tea, Hutchinson’s sons and the other consignees were keeping low profiles, and everyone was on tenterhooks waiting for the first East India Company cargo to arrive.

According to merchant John Rowe, that Thanksgiving saw “Dull heavy Raw Weather.”

Friday, November 24, 2023

“Three days after the Boston Tea Party”

In 1966, Congress and President Lyndon B. Johnson established the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission.

That body would accomplish little, but it shows that some Americans were looking ahead to the anniversaries of the Revolution.

On 16 December of that year, the Disabled American Veterans of Massachusetts performed a reenactment of the Boston Tea Party. The first replica ship wouldn’t open for another seven years, so they used another sailing vessel moored along the waterfront.

The next day, people in Marshfield reenacted the burning of tea in their town. According to the Quincy Patriot-Ledger, this commemoration took place “at the foot of Tea Rock Hill.” The tea was paraded from “the old Proctor Bourne Store (now LaForest’s),” and a Bourne descendant set it alight. There was a handbell choir.

The Patriot-Ledger’s stories on the event, both before and after, quoted liberally from Joseph C. Hagar’s tercentenary history of Marshfield, as I did yesterday.

The newspaper said the tea-burning in Marshfield happened “a few nights after the famous Boston Harbor event in December, 1773,” but was no more specific than that.

Ten years later, a Bicentennial publication pinned the event to a specific date. Of Tea and Tories was written by Cynthia Hagar Krusell, a granddaughter of Joseph C. Hagar and also a descendant of someone named Thomas involved in the original burning. (Two families named Thomas were among the first English settlers in the town, so by 1773 this could mean any number of people.)

Krusell was vice-chairman of the Marshfield Bicentennial Committee, which published her booklet in 1976. A trained artist, she drew a map and genealogies for it. About the tea-burning she wrote:

In 1773, the 19th of December was a Sunday. People gathered in their congregations, and they probably did discuss the destruction of the tea in Boston. However, New Englanders tended not to carry out political actions from Saturday night through Sunday night, viewing that stretch as the Sabbath.

COMING UP: After a Thanksgiving break, lingering questions.

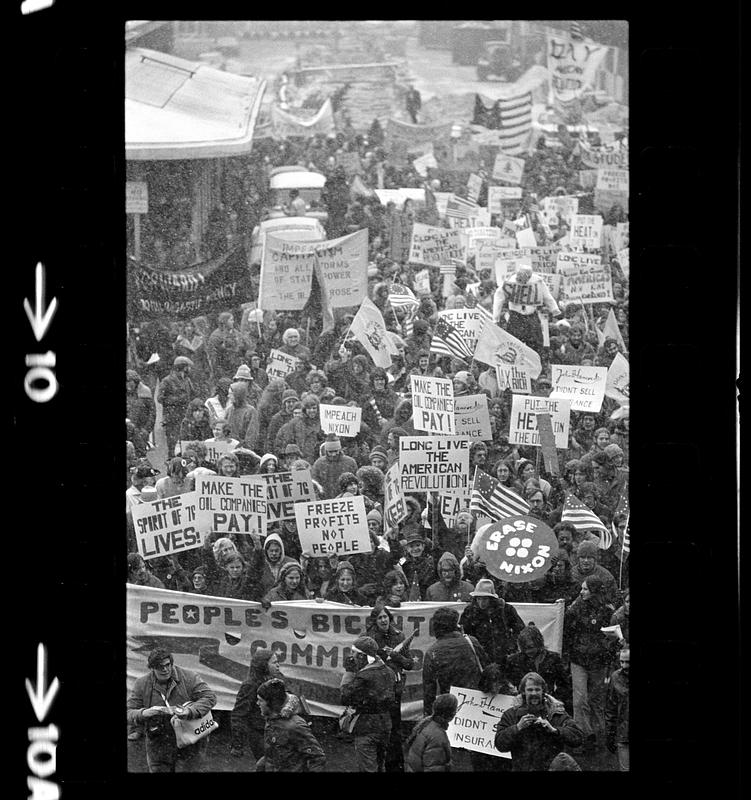

(I couldn’t find good photographs of the 1966 reenactments. The photo above, courtesy of Digital Commonwealth, shows a different Disabled American Veterans demonstration aboard the recreated tea ship Beaver, probably in 1979 or 1980, since the group was protesting Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.)

That body would accomplish little, but it shows that some Americans were looking ahead to the anniversaries of the Revolution.

On 16 December of that year, the Disabled American Veterans of Massachusetts performed a reenactment of the Boston Tea Party. The first replica ship wouldn’t open for another seven years, so they used another sailing vessel moored along the waterfront.

The next day, people in Marshfield reenacted the burning of tea in their town. According to the Quincy Patriot-Ledger, this commemoration took place “at the foot of Tea Rock Hill.” The tea was paraded from “the old Proctor Bourne Store (now LaForest’s),” and a Bourne descendant set it alight. There was a handbell choir.

The Patriot-Ledger’s stories on the event, both before and after, quoted liberally from Joseph C. Hagar’s tercentenary history of Marshfield, as I did yesterday.

The newspaper said the tea-burning in Marshfield happened “a few nights after the famous Boston Harbor event in December, 1773,” but was no more specific than that.

Ten years later, a Bicentennial publication pinned the event to a specific date. Of Tea and Tories was written by Cynthia Hagar Krusell, a granddaughter of Joseph C. Hagar and also a descendant of someone named Thomas involved in the original burning. (Two families named Thomas were among the first English settlers in the town, so by 1773 this could mean any number of people.)

Krusell was vice-chairman of the Marshfield Bicentennial Committee, which published her booklet in 1976. A trained artist, she drew a map and genealogies for it. About the tea-burning she wrote:

The first rebel action occurred at midnight December 19, 1773, three days after the Boston Tea Party. A band of local Patriots, emboldened by fellow rebels in Boston, crept by night into the John Bourne ordinary by the town training green. They seized boxes of British tea stored there and in Nehemiah Thomas’s cellar, piled them on an ox-drawn wagon and silently bore them to “a stone quite flat on top” which stood on the crest of a nearby hill, thereafter immortalized as Tea Rock Hill.So far as I can tell, Krusell’s publication was the first to specify a date for the burning, 19 December. But she didn’t cite evidence for that detail or others. Nothing in her list of sources leaps out to suggest the date came from a diary or other document that previous historians hadn’t seen.

Sensing the impact of the moment, they knelt in humble prayer while Jeremiah Lowe touched the tea with his torch, igniting simultaneously the spark of Revolutionary fervor in Marshfield.

In 1773, the 19th of December was a Sunday. People gathered in their congregations, and they probably did discuss the destruction of the tea in Boston. However, New Englanders tended not to carry out political actions from Saturday night through Sunday night, viewing that stretch as the Sabbath.

COMING UP: After a Thanksgiving break, lingering questions.

(I couldn’t find good photographs of the 1966 reenactments. The photo above, courtesy of Digital Commonwealth, shows a different Disabled American Veterans demonstration aboard the recreated tea ship Beaver, probably in 1979 or 1980, since the group was protesting Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.)

Thursday, November 23, 2023

The Tercentenary Telling of the Marshfield Tea Burning

In 1940, the town of Marshfield celebrated the 300th anniversary of its founding.

Among the projects of the Tercentenary Committee was the publication of a new town history assembled by Joseph C. Hagar, who had succeeded Lysander S. Richards as head of the local historical society.

That book’s title page says: Marshfield 70°–40´W : 42°–5´N: The Autobiography of a Puritan Town. Book cataloguers have been divided on whether the title includes that longitude and latitude, or whether they’re just too much trouble.

On the burning of tea in the town, Hagar wrote:

This book adds a couple of details to the story of the tea burning, such as the pause for prayer before the bonfire—apparently based on what Charles Petersen’s grandmother told him.

Most important, Hagar’s recounting specified a new location for the stash of confiscated tea: “the former old John Bourne store.” In terms of commemoration, that had a couple of advantages over Deacon Nehemiah Thomas’s house, the only place previously named:

TOMORROW: Two generations on, and the first reenactment.

Among the projects of the Tercentenary Committee was the publication of a new town history assembled by Joseph C. Hagar, who had succeeded Lysander S. Richards as head of the local historical society.

That book’s title page says: Marshfield 70°–40´W : 42°–5´N: The Autobiography of a Puritan Town. Book cataloguers have been divided on whether the title includes that longitude and latitude, or whether they’re just too much trouble.

On the burning of tea in the town, Hagar wrote:

The British had brought a large quantity of tea to the town, which they were unable to sell on account of the high price. They stored it in various places in the village.Hagar’s book doesn’t cite evidence for specific statements. It echoes passages from sources like the D.A.R. description of the event, sometimes word for word, without acknowledgment. It contains errors. (There was no Jonathan Bourne, for instance.) All that makes it a frustrating source to work with, but it was the towns’s official tercentenary history.

On the southwest side of the old Marshfield Training Green is a hill on which now stands quite a modern residence. This hill is known as Tea Rock Hill, although the rock itself has been blasted and pieces used in the foundations of two nearby homes. The ledge, however, is still visible.

Not far away toward the South river, but northeast from the hill, stands the former old John Bourne store, now a fairly modern Post Office. The store was built in 1709. Toward the east are two houses of interest, both being old Thomas homes. . . . [One was] the residence of Nehemiah Thomas; and in his cellar was stored some of the tea which had been brought into the town. More tea was stored in the old Bourne store.

A few days after the Boston Tea Party, the enthusiastic patriots of Marshfield (one of whom, Jonathan Bourne, fought in the battle of Bunker Hill) marched quietly and earnestly to these places and secured the tea there stored. This act required courage and conviction as Marshfield had such a strong Tory element. The tea was loaded onto an ox-cart and hauled to Tea Rock Hill.

Among the patriots were women and children as well as men. Mr. Charles Peterson remembers that his grandmother told him she was one of the group.

On the top of the hill they placed the tea “upon a stone quite flat on top” and as it was evening, they knelt in the dim light of the primitive lanterns and offered prayer. A torch carried by Jeremiah Lowe was applied to the tea and it was burned. Jeremiah Lowe was later forced to flee to New York with his family.

This book adds a couple of details to the story of the tea burning, such as the pause for prayer before the bonfire—apparently based on what Charles Petersen’s grandmother told him.

Most important, Hagar’s recounting specified a new location for the stash of confiscated tea: “the former old John Bourne store.” In terms of commemoration, that had a couple of advantages over Deacon Nehemiah Thomas’s house, the only place previously named:

- First, it was closer to Tea Rock Hill, making for a more compact commemoration.

- Second, it still existed, albeit as a part of a larger building.

TOMORROW: Two generations on, and the first reenactment.

Wednesday, November 22, 2023

Tea Burning on Marshfield Town Green, 26 Nov.

On Sunday, 26 November, a bevy of organizations—Historic Winslow House, Revolution250, the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum, and Old Town Trolley Tours—will commemorate the burning of tea in Marshfield.

The “Revolution Brewing” event will feature a sestercentennial reenactment on the town green, with parking available at town hall. The schedule comes in three phases.

2:00 to 3:00 P.M.

Welcoming proclamation, fife & drum music, the march of the local militia, and a mock drill eighteenth-century games for children. Hot chocolate will be available for purchase.

3:00 to 4:00 P.M.

Locals portray Whigs and Loyalists debating the historical events that led to the crisis over tea at the end of 1773. As I’ve written, Marshfield was pretty evenly split between friends of the royal government and their opponents. Therefore, unlike in most places—and particularly in, say, a Boston or Lexington town meeting—men and women on both sides did feel free to speak their minds.

At the end of this hour, the radical Whigs will burn tea to show their solidarity with the mysterious figures who destroyed the East India Company cargos in Boston, and with all those North American boycotting tea to protest Parliament’s tax on it.

4:00 to 5:00 P.M.

Presentation on the aftermath of the tea crisis and what would lie ahead for Marshfield in 1774. The town became the only territory in modern Massachusetts outside of Boston that the royal authorities controlled at the start of the war.

Folks are invited to bring loose tea to be burned or sent to Boston to be dumped into the harbor in the 16 December reenactment of the Boston Tea Party.

TOMORROW: Back to the historical inquiry.

[The photo above comes from a recent tea burning in Lexington. That town has been reenacting its tea-burning for a few years now while Marshfield is doing it especially for this anniversary year. I’ll be running info on Lexington’s 2023 event soon.]

The “Revolution Brewing” event will feature a sestercentennial reenactment on the town green, with parking available at town hall. The schedule comes in three phases.

2:00 to 3:00 P.M.

Welcoming proclamation, fife & drum music, the march of the local militia, and a mock drill eighteenth-century games for children. Hot chocolate will be available for purchase.

3:00 to 4:00 P.M.

Locals portray Whigs and Loyalists debating the historical events that led to the crisis over tea at the end of 1773. As I’ve written, Marshfield was pretty evenly split between friends of the royal government and their opponents. Therefore, unlike in most places—and particularly in, say, a Boston or Lexington town meeting—men and women on both sides did feel free to speak their minds.

At the end of this hour, the radical Whigs will burn tea to show their solidarity with the mysterious figures who destroyed the East India Company cargos in Boston, and with all those North American boycotting tea to protest Parliament’s tax on it.

4:00 to 5:00 P.M.

Presentation on the aftermath of the tea crisis and what would lie ahead for Marshfield in 1774. The town became the only territory in modern Massachusetts outside of Boston that the royal authorities controlled at the start of the war.

Folks are invited to bring loose tea to be burned or sent to Boston to be dumped into the harbor in the 16 December reenactment of the Boston Tea Party.

TOMORROW: Back to the historical inquiry.

[The photo above comes from a recent tea burning in Lexington. That town has been reenacting its tea-burning for a few years now while Marshfield is doing it especially for this anniversary year. I’ll be running info on Lexington’s 2023 event soon.]

Tuesday, November 21, 2023

“To praise their act is to set a bad example”

On 8 Aug 1929, two days after the Boston Herald reported on the dedication of a historic marker at Marshfield’s Tea Rock Hill, the newspaper ran this letter to the editor:

Some internet sleuthing indicates that Cosgrave graduated from Indiana University in 1909 and studied economics at Harvard University as the Henry Lee Memorial Fellow. He then taught economics at Indiana, the Carnegie Institute of Technology, and the Pittsburgh Trade Union College.

By the mid-1920s Cosgrave was working for the Workers’ Education Bureau of America, established to assist labor colleges and worker training centers. He gave speeches and published articles with titles like “Labor in the Ancient World,” “Is Rent Justifiable,” “Organized Labor and the Schools,” and “Christmas Clubs.” (Sometimes his last name was reported as “Cosgrove.”)

In April 1929, a few months before his letter about the Marshfield tea burning, Cosgrave signed letters to the Columbus Evening Dispatch identifying himself as publicity agent for the Ohio State Federation of Labor. That same year, the American Federation of Labor took over the W.E.B.A. and pulled it away from more radical unions. Cosgrave remained active in the labor movement, whether or not with that organization, because around 1940 the A.F.L. was promoting his series of articles titled “After the War.”

I haven’t found any source linking Cosgrave to Framingham aside from this letter. Having grown up in Muncie, he was back there by 1933, and seems to have done most of his work in the country’s industrial heartland. But his job took him to speak to many groups of workers. Perhaps Cosgrave was traveling through Massachusetts in August 1929, saw the Boston Herald article, and had to comment on the irony of the D.A.R. commemorating the destruction of private property to make a political point.

For nearly two hundred years now, per the argument in Alfred F. Young’s The Shoemaker and the Tea Party, Americans have debated the political resonance of the Boston Tea Party for contemporary issues. Cosgrave’s letter extended the same argument to the Marshfield tea burning.

Most Americans have agreed, perhaps based on nothing more than pictures in their schoolbooks, that the colonial resistance to the Tea Act of 1773 is a fine model of political activism. But is the lesson that sometimes protesters need to destroy private property to make their point and save society from a worse fate? Or is it that the good protests were tightly controlled and, furthermore, deep in the past, over esoteric issues that have little relevance today?

TOMORROW: This weekend in Marshfield.

(The photo above, courtesy of Digital Commonwealth, shows the People’s Bicentennial Commission demonstrating at Faneuil Hall during the Boston Tea Party bicentennial in 1973.)

The Tea Rock chapter, D.A.R., did a very questionable thing yesterday when it dedicated a bronze tablet to the memory of the men of Marshfield who in 1773 burned tea brought there by the British to sell. After all, that tea was private property and it was illegal for the men of Marshfield to burn it. and to praise their act is to set a bad example before certain elements today.Because sarcasm is just as hard to detect in ink as in pixels, the paper headlined this letter “SATIRICAL.”

LLOYD M. COSGRAVE.

Framingham, Aug. 6.

Some internet sleuthing indicates that Cosgrave graduated from Indiana University in 1909 and studied economics at Harvard University as the Henry Lee Memorial Fellow. He then taught economics at Indiana, the Carnegie Institute of Technology, and the Pittsburgh Trade Union College.

By the mid-1920s Cosgrave was working for the Workers’ Education Bureau of America, established to assist labor colleges and worker training centers. He gave speeches and published articles with titles like “Labor in the Ancient World,” “Is Rent Justifiable,” “Organized Labor and the Schools,” and “Christmas Clubs.” (Sometimes his last name was reported as “Cosgrove.”)

In April 1929, a few months before his letter about the Marshfield tea burning, Cosgrave signed letters to the Columbus Evening Dispatch identifying himself as publicity agent for the Ohio State Federation of Labor. That same year, the American Federation of Labor took over the W.E.B.A. and pulled it away from more radical unions. Cosgrave remained active in the labor movement, whether or not with that organization, because around 1940 the A.F.L. was promoting his series of articles titled “After the War.”

I haven’t found any source linking Cosgrave to Framingham aside from this letter. Having grown up in Muncie, he was back there by 1933, and seems to have done most of his work in the country’s industrial heartland. But his job took him to speak to many groups of workers. Perhaps Cosgrave was traveling through Massachusetts in August 1929, saw the Boston Herald article, and had to comment on the irony of the D.A.R. commemorating the destruction of private property to make a political point.

For nearly two hundred years now, per the argument in Alfred F. Young’s The Shoemaker and the Tea Party, Americans have debated the political resonance of the Boston Tea Party for contemporary issues. Cosgrave’s letter extended the same argument to the Marshfield tea burning.

Most Americans have agreed, perhaps based on nothing more than pictures in their schoolbooks, that the colonial resistance to the Tea Act of 1773 is a fine model of political activism. But is the lesson that sometimes protesters need to destroy private property to make their point and save society from a worse fate? Or is it that the good protests were tightly controlled and, furthermore, deep in the past, over esoteric issues that have little relevance today?

TOMORROW: This weekend in Marshfield.

(The photo above, courtesy of Digital Commonwealth, shows the People’s Bicentennial Commission demonstrating at Faneuil Hall during the Boston Tea Party bicentennial in 1973.)

Monday, November 20, 2023

“We have a rock that is a relic of the Revolution”

The wonderfully named Lysander Salmon Richards (1835–1926, shown here) published a two-volume History of Marshfield in 1901 and 1905.

In the first volume he summed up what authors of the previous century had written about how locals had burned tea during the fraught last weeks of 1773:

By that point, the landscape of Revolutionary Marshfield had changed—literally. To the dismay of the town’s first chronicler, Marcia A. Thomas, Tea Rock had been blasted into pieces, some of them used for the foundations of nearby houses. That’s why Richards wrote, “what there is remaining of it.” Nehemiah Thomas’s house was also gone.

Some Marshfield residents were determined to keep that story alive, though. In 1916 the town some local women established the Tea Rock Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. On 5 Aug 1929 they unveiled a historic marker on Tea Rock Hill.

The next day’s Boston Herald laid out that generation’s understanding of the historic event:

TOMORROW: Objections and details.

In the first volume he summed up what authors of the previous century had written about how locals had burned tea during the fraught last weeks of 1773:

We do not have in Marshfield an historic rock, like Plymouth Rock, a relic of the Pilgrims, but we have a rock that is a relic of the Revolution. When the Boston Tea Party threw overboard in the Boston Harbor all the tea on the ships in the harbor, the patriots of Marshfield learned there was a large quantity of tea secreted by some authorities in the cellar of a house on the site now occupied by Mr. Seaverns, two or three hundred feet from the street leading from the First Congregational church to the Marshfield station.In the second volume Richards included a close rewrite of what members of the White family had written about their ancestor ten years before:

The Marshfield patriots, not to be outdone by the Boston tea sinkers, marched to the said house and demanded the tea. Resistance being useless, it was given up and carried to a rock on a hill directly opposite Dr. Stephen Henry’s residence, not far from the First Congregational church, and there heaped upon this huge rock, it was set afire and burned to ashes. This rock (what there is remaining of it) has since been called “Tea Rock.”

Mr. [Benjamin] White was commissioned to collect the tea after it was voted not to drink it. They stored it in the house of Nehemiah Thomas. Saving the tea at that time did not satisfy those earnest, honest whigs, so they took this confiscated article and carried it into a nearby field, where there was a large rock, “flatt on ye top,” pouring it thereon, and then Mr. White and his brother-in-law, Jeremiah Low, (two staunch old whigs,) applied the torch amid rejoicings.To compare those paragraphs with the passages I quoted yesterday, it looks like Richards didn’t add any facts to the story besides who lived in the houses in his time.

By that point, the landscape of Revolutionary Marshfield had changed—literally. To the dismay of the town’s first chronicler, Marcia A. Thomas, Tea Rock had been blasted into pieces, some of them used for the foundations of nearby houses. That’s why Richards wrote, “what there is remaining of it.” Nehemiah Thomas’s house was also gone.

Some Marshfield residents were determined to keep that story alive, though. In 1916 the town some local women established the Tea Rock Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. On 5 Aug 1929 they unveiled a historic marker on Tea Rock Hill.

The next day’s Boston Herald laid out that generation’s understanding of the historic event:

…the men of Marshfield…in December, 1773, burned tea brought here by the British after the latter had failed to sell it to the public at a high price.The story had changed in the quarter-century since Richards’s writing. For some reason, the problem with the tea was that it was too expensive, not that it was taxed. An ox cart made its first appearance in the story, though it would have been a logical assumption before. The tea came from several unstated locations, not just Nehemiah Thomas’s house. Indeed, there was no mention of Thomas or Benjamin White, another documented political leader of the time. Only Jeremiah Low’s name was molded into the tablet.

So much of the tea remained unsold that the British stored it in various parts of the village. Then, one night, patriots raided these places, loaded the tea onto an ox cart, hauled it to the top of the elevation known as Tea Rock hill, on which the residence of Elijah Ames now stands, and burned it.

The torch was applied by Jeremiah Lowe, who was later forced to flee to New York with his family. . . . John and Mary Ford, children of Edward Ford of Marshfield, direct descendants of Jeremiah Lowe, assisted in unveiling the tablet, which is affixed to a large granite boulder.

The memorial is inscribed as follows:

“On this hill, in December, 1773, the staunch Whig, Jeremiah Lowe, applied the torch which burned the tea confiscated by the patriots from the public and private stores of the town of Marshfield. Erected by Tea Rock Chapter, D.A.R. of Marshfield, 1929.” . . .

Miss Louise Wardsworth, regent of Tea Rock Chapter, read the history of the burning of the tea, and vocal solos were given by Miss Elsie Sennott.

TOMORROW: Objections and details.

Sunday, November 19, 2023

Bad Day at Tea Rock

As I recounted back in 2016, Marshfield was unusually split in the last years before the war. Some influential men supported the Crown, and some opposed it.

Control of town meetings went back and forth, and the faction that was outvoted in the official meeting would gather and grumble about the results.

One documented leader of the local resistance was Nehemiah Thomas (1712–1782), both treasurer and clerk for the town as well as a deacon at the meetinghouse.

Another was Benjamin White (1725–1783), who sometimes filled in as clerk and would also represent the town in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress.

In late 1773 Marshfield got into a tussle over tea. The official side of that dispute is documented in the record of a town meeting on 31 Jan 1774 that protested the Boston Tea Party, and then a protest against that protest, both published in the Boston newspapers.

However, there appears to have been more direct action in December, not described in writing until decades later.

The first mention of this incident I’ve found was in Marcia A. Thomas’s Memorials of Marshfield (1854):

TOMORROW: Traditions in the twentieth century.

[The photograph of the marker on Marshfield’s Tea Rock Hill comes from Patrick Browne, who in his Historical Digression blog synthesized the accounts of the town’s tea-burning.]

Control of town meetings went back and forth, and the faction that was outvoted in the official meeting would gather and grumble about the results.

One documented leader of the local resistance was Nehemiah Thomas (1712–1782), both treasurer and clerk for the town as well as a deacon at the meetinghouse.

Another was Benjamin White (1725–1783), who sometimes filled in as clerk and would also represent the town in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress.

In late 1773 Marshfield got into a tussle over tea. The official side of that dispute is documented in the record of a town meeting on 31 Jan 1774 that protested the Boston Tea Party, and then a protest against that protest, both published in the Boston newspapers.

However, there appears to have been more direct action in December, not described in writing until decades later.

The first mention of this incident I’ve found was in Marcia A. Thomas’s Memorials of Marshfield (1854):

While [Nehemiah Thomas was] absent, on one of these occasions, the whigs of the vicinity, in the ardor of their patriotism, took from his house, contrary to his intention, a quantity which had been seized by them and deposited there. This was burnt on a rock, near the meetinghouse, with much eclat. This was known afterwards as Tea Rock.In the 13 Sept 1869 Springfield Republican I found this:

A few rods from the Marshfield post-office is “Tea-rock hill.” During the revolutionary period all the tea was secreted in the entry of one of the colonists. While he was at Boston, attending the Continental Congress [sic], a few ardent whigs, who did not believe in the soothing qualities of tea bearing a British tax, seized and burned it upon the hill’s summit.L. Vernon Briggs’s History of Shipbuilding on North River (1889) devoted a footnote to the memories of Isaac Thomas (1765–1859), including:

He saw the burning of the obnoxious tea on the height which yet bears its name, and saw the torch touched to the fire fated pile by that devoted Whig, Jeremiah Low.Thomas and Samuel White’s family history published in 1895 stated:

Benjamin White was one of the committee to collect the tea after it was voted not to use it, and it was stored in Nehemiah Thomas’s house. He did not feel satisfied with this, it looked as if saved for future use. When the Whigs of the vicinity, in the ardor of their patriotism, seized this tea, carrying it into a field near by, where there was a large rock which was “flat on ye top,” poured the tea thereon, when Benjamin White and his brother-in-law, Jeremiah Low, two staunch old Whigs, God bless them! applied the torch with much rejoicing. This was known ever afterwards as “Tea Rock.”The following year, Caleb A. Wall borrowed much of that language for The Historic Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773.

TOMORROW: Traditions in the twentieth century.

[The photograph of the marker on Marshfield’s Tea Rock Hill comes from Patrick Browne, who in his Historical Digression blog synthesized the accounts of the town’s tea-burning.]

Saturday, November 18, 2023

Fichter on the Fate of the Tea

We’re one month out from the sestercentennial of the Boston Tea Party, so we’ll be consuming an increasing amount of that topic.

The anniversary has brought a new study of British North America’s tea crisis: Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776 by James R. Fichter.

Fichter is a professor of international history at the University of Hong Kong, closer to where the Chinese tea began its global journey than to where it went into the salt water. He is also the author of So Great a Proffit: How the East Indies Transformed Anglo-American Capitalism and editor of British and French Colonialism in Africa, Asia and the Middle East: Connected Empires across the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Centuries.

Tea looks at the data on consumption and sale of tea in North America, showing that people continued to consume it even as it became freighted with political meaning. It was a source of caffeine, after all.

In fact, Fichter points out, of the five ships carrying East India Company tea that landed in America, one way or another, two cargos were eventually consumed on the continent. Champions of the traditional narrative might respond that none of that tea was drunk by Patriot Americans under Crown government as initially intended. Details are in the book.

Earlier this month, Fichter chatted long-distance with the Emerging Revolutionary War team. The recording of that discussion can be viewed on Facebook and on YouTube.

Fichter will also be in Boston on 16 December as one of the speakers at the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts’s Tea Party Symposium. You can now use that link to register for a seat in advance.

The anniversary has brought a new study of British North America’s tea crisis: Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776 by James R. Fichter.

Fichter is a professor of international history at the University of Hong Kong, closer to where the Chinese tea began its global journey than to where it went into the salt water. He is also the author of So Great a Proffit: How the East Indies Transformed Anglo-American Capitalism and editor of British and French Colonialism in Africa, Asia and the Middle East: Connected Empires across the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Centuries.

Tea looks at the data on consumption and sale of tea in North America, showing that people continued to consume it even as it became freighted with political meaning. It was a source of caffeine, after all.

In fact, Fichter points out, of the five ships carrying East India Company tea that landed in America, one way or another, two cargos were eventually consumed on the continent. Champions of the traditional narrative might respond that none of that tea was drunk by Patriot Americans under Crown government as initially intended. Details are in the book.

Earlier this month, Fichter chatted long-distance with the Emerging Revolutionary War team. The recording of that discussion can be viewed on Facebook and on YouTube.

Fichter will also be in Boston on 16 December as one of the speakers at the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts’s Tea Party Symposium. You can now use that link to register for a seat in advance.

Friday, November 17, 2023

Peering into a Prison in 1799

Richard Brunton (1749–1832) came to America to fight for his king as a grenadier in the 38th Regiment. That lasted until 1779, when he deserted.

As Deborah M. Child relates in her biography, Soldier, Engraver, Forger, Brunton struggled to make an honest living in New England with his talent and training as an engraver.

One product he kept coming back to was family registers and other genealogical forms. Another was counterfeit currency.

In 1799 the state of Connecticut sent Brunton to the Old New-Gate Prison in East Granby for forging coins. To pay his accompanying fine, he made art, including a portrait of Gov. Jonathan Trumbull, a seal of the state arms, and a picture of Old New-Gate itself.

That prison, also known as the Simsbury Mines, was notorious as a place where the state held Loyalists underground during the Revolutionary War. However, in 1790 the state took over the property and rebuilt it according to a modern philosophy of criminal punishment, based on locking people up for years doing labor instead of physically punishing or hanging them. Brunton depicted the place he came to know during his two-year sentence.

The Boston Rare Maps page for this print says:

The copperplate for Brunton’s Old New-Gate image survived until about 1870, when a few more prints were made. Only a handful of copies survive, and it’s impossible to tell whether they came from the initial run or the reprint decades after the artist died.

The example shown above was recently acquired by the John Carter Brown Library in Rhode Island. Other prints are at the Connecticut Historical Society and the Massachusetts Historical Society.

As Deborah M. Child relates in her biography, Soldier, Engraver, Forger, Brunton struggled to make an honest living in New England with his talent and training as an engraver.

One product he kept coming back to was family registers and other genealogical forms. Another was counterfeit currency.

In 1799 the state of Connecticut sent Brunton to the Old New-Gate Prison in East Granby for forging coins. To pay his accompanying fine, he made art, including a portrait of Gov. Jonathan Trumbull, a seal of the state arms, and a picture of Old New-Gate itself.

That prison, also known as the Simsbury Mines, was notorious as a place where the state held Loyalists underground during the Revolutionary War. However, in 1790 the state took over the property and rebuilt it according to a modern philosophy of criminal punishment, based on locking people up for years doing labor instead of physically punishing or hanging them. Brunton depicted the place he came to know during his two-year sentence.

The Boston Rare Maps page for this print says:

The view suggests that coopering (barrel making) was a major activity for prisoners, as two figures can be seen at upper right engaged in the task, while another at the bottom seems to be bringing a completed barrel to a shed.After being released, Brunton went back to Boston, where he was arrested for counterfeiting again in 1807. He served more years in a Massachusetts state prison and finally lived out his life in Groton.

Also visible are what appear to be two African-American figures carrying buckets can be seen in the view; these figures, which are completely blackened, stand out conspicuously from the others in the view. It is documented that enslaved African-Americans worked in the copper mine that had earlier operated in the location of the prison. Whether African-American were also engaged at the prison as well is a question for further research raised by this work.

Although the engraving contains an image of a prisoner receiving the lash, as a state prison Newgate followed a relatively humane approach for the period; a prisoner could be given no more than 10 lashes, and there was a limit on time served there. Participation in labor was required of all prisoners, and in addition to coopering they also engaged in nail making, blacksmithing, wagon and plow manufacture, shoe making, basket weaving and machining.

The copperplate for Brunton’s Old New-Gate image survived until about 1870, when a few more prints were made. Only a handful of copies survive, and it’s impossible to tell whether they came from the initial run or the reprint decades after the artist died.

The example shown above was recently acquired by the John Carter Brown Library in Rhode Island. Other prints are at the Connecticut Historical Society and the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Thursday, November 16, 2023

Dickinson Biography to be Published in 2024

More than eleven years ago I posted this observation about how many books on Thomas Paine had come out in recent years, belying his fans’ claim that he was a neglected Founder.

As I wrote that, I looked around for a foil and landed on this:

Nonetheless, back in 2011 I could find only two recent books on Dickinson, one from a press affiliated with the National Review and the other by Jane Calvert, apparently based on her doctoral dissertation.

Calvert went on to launch the John Dickinson Writings Project, where she is Director and Chief Editor, as well as becoming a professor at the University of Kentucky.

Oxford University Press has just announced that next summer it will publish Penman of the Founding: A Biography of John Dickinson by Calvert. This will be the first full, scholarly, modern biographer of this important and unique figure among the Founders.

Ironically, Calvert’s university webpage says, “Professor Calvert has also produced work on Thomas Paine.” So it’s possible to do both!

As I wrote that, I looked around for a foil and landed on this:

Let’s compare Paine to, say, John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, author of Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, the most influential American political essay before Common Sense.Dickinson made even more contributions to the American cause, such as writing the first draft of the Articles of Confederation and chairing the Annapolis Convention.

In addition to writing that book and “The Liberty Song,” Dickinson was an important delegate to the Continental Congress, top official of Pennsylvania’s wartime government, and a delegate to the Constitutional Convention.

Dickinson was on the losing side of the debate over the Declaration of Independence but on the right side of the debate over slavery.

Nonetheless, back in 2011 I could find only two recent books on Dickinson, one from a press affiliated with the National Review and the other by Jane Calvert, apparently based on her doctoral dissertation.

Calvert went on to launch the John Dickinson Writings Project, where she is Director and Chief Editor, as well as becoming a professor at the University of Kentucky.

Oxford University Press has just announced that next summer it will publish Penman of the Founding: A Biography of John Dickinson by Calvert. This will be the first full, scholarly, modern biographer of this important and unique figure among the Founders.

Ironically, Calvert’s university webpage says, “Professor Calvert has also produced work on Thomas Paine.” So it’s possible to do both!

Wednesday, November 15, 2023

Gomes Prize for The Contagion of Liberty

On 15 Nov 1773, 250 years ago today, the Essex Hospital on an island off Marblehead took in its second round of patients for smallpox inoculation.

The dispute over that hospital, which culminated in its destruction in late January, is a reminder that not all conflicts in Revolutionary New England broke down along the lines of Patriot v. Loyalist.

Some of the local merchants who had invested in the hospital were stalwarts of the local resistance—as were some of the local laborers and seamen who destroyed it.

That sestercentennial anniversary seems like a good occasion to note that the Massachusetts Historical Society just gave the 2023 Peter J. Gomes Memorial Book Prize for best nonfiction work on the history of Massachusetts to Andrew M. Wehrman for The Contagion of Liberty: The Politics of Smallpox in the American Revolution.

Wehrman is a professor of history at Central Michigan University. Back in 2008, he received the Walter Muir Whitehill Award for his article, “The Siege of ‘Castle Pox’: A Medical Revolution in Marblehead, Massachusetts, 1764–1777.” Wehrman’s book expands on that incident to trace the debate over how to fight smallpox through the Revolutionary War.

By that time, most people understood how inoculation worked—the scientific dispute had been settled decades earlier. But there were practical problems of isolating people who had been inoculated until they stopped being infectious. Those problems were why folks in Essex County destroyed the smallpox hospital off their coast, and why Gen. George Washington waited so long before having his troops inoculated.

The dispute over that hospital, which culminated in its destruction in late January, is a reminder that not all conflicts in Revolutionary New England broke down along the lines of Patriot v. Loyalist.

Some of the local merchants who had invested in the hospital were stalwarts of the local resistance—as were some of the local laborers and seamen who destroyed it.

That sestercentennial anniversary seems like a good occasion to note that the Massachusetts Historical Society just gave the 2023 Peter J. Gomes Memorial Book Prize for best nonfiction work on the history of Massachusetts to Andrew M. Wehrman for The Contagion of Liberty: The Politics of Smallpox in the American Revolution.

Wehrman is a professor of history at Central Michigan University. Back in 2008, he received the Walter Muir Whitehill Award for his article, “The Siege of ‘Castle Pox’: A Medical Revolution in Marblehead, Massachusetts, 1764–1777.” Wehrman’s book expands on that incident to trace the debate over how to fight smallpox through the Revolutionary War.

By that time, most people understood how inoculation worked—the scientific dispute had been settled decades earlier. But there were practical problems of isolating people who had been inoculated until they stopped being infectious. Those problems were why folks in Essex County destroyed the smallpox hospital off their coast, and why Gen. George Washington waited so long before having his troops inoculated.

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

“The famous Jacob Bates hath lately exhibited here”

We last left the equestrian Jacob Bates as he arrived in Newport, having already exhibited his skills in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston.

As I noted then, Bates didn’t advertise in Rhode Island newspapers the way he’d done in those other cities. Thus, we don’t have that sort of evidence about his shows.

But we do have a description written on 14 Nov 1773, 250 years ago today, in a letter by the lawyer William Ellery (1727–1820, shown here):

The “Mr. Honyman” who provided land for Bates’s display was probably James Honeyman, Esq. (1710–1778), a prominent lawyer and broker of marine insurance. His namesake father had been rector of Newport’s Trinity Church. In the early part of his career Honeyman was elected to various offices, including Rhode Island attorney general. By this time, however, he held royal appointments instead since he leaned toward the Crown in politics. During the war Honeyman resigned his remaining government posts and tried to sit out disputes.

William Ellery himself went on to represent Rhode Island in the Second Continental Congress, arriving just in time to vote for and sign the Declaration of Independence and remaining until 1785.

As I noted then, Bates didn’t advertise in Rhode Island newspapers the way he’d done in those other cities. Thus, we don’t have that sort of evidence about his shows.

But we do have a description written on 14 Nov 1773, 250 years ago today, in a letter by the lawyer William Ellery (1727–1820, shown here):

But I cannot bid you adieu in this solemn manner. Totus mundus agit histrionem. [The whole world’s a stage.] The famous Jacob Bates hath lately exhibited here his most surprising feats of horsemanship, in a circus or enclosure of about one hundred and twenty feet in diameter, erected at the east end of Mr. Honyman’s field. The number of spectators was from three to seven hundred. He exhibited four times, and took half a dollar for a ticket.Like the person who wrote to the Boston Evening-Post quoted here, Ellery saw Bates as the sort of London showman that good New Englanders should beware of. Yet he also viewed that particular equestrian act as better than other theatricals. Indeed, he appears to have enjoyed the spectacle.

A mountebank doctor, who lately came into America from some part of Europe, (Great Britain, I believe,) and who is expected here, is now haranguing daily, from a wagon, to the good gaping people of Connecticut, and, while they are gaping, he is picking their pockets. Strolling players we have had among us. I expect that, in a few years, Drury Lane and Sadler’s Wells, &c., will be translated into America.

I wish, while we are encouraging the importation of the amusements, follies, and vices of Great Britain, America would encourage the introduction of her virtues, if she have any; for I am sure, by thus countenancing her follies and vices, we shall lose the little stock of virtue that is left among us. This I am very clear in, that exhibitions of players, rope-dancers, and mountebanks, (I must confess, indeed, there is something manly and generous in the exhibitions of Mr. Bates; for a well-formed man, and a well-shaped, well-limbed, well-sized horse, are fine figures, and in his manage are displayed amazing strength, resolution, and activity,) have a more effectual tendency, by disembowelling the purse, and enfeebling the mind, to sap the foundations of patriotism and public virtue, than any of the yet practised efforts of a despotic ministry. But it will be in vain to talk against these things, while there are a hundred fools to one wise man.

The “Mr. Honyman” who provided land for Bates’s display was probably James Honeyman, Esq. (1710–1778), a prominent lawyer and broker of marine insurance. His namesake father had been rector of Newport’s Trinity Church. In the early part of his career Honeyman was elected to various offices, including Rhode Island attorney general. By this time, however, he held royal appointments instead since he leaned toward the Crown in politics. During the war Honeyman resigned his remaining government posts and tried to sit out disputes.

William Ellery himself went on to represent Rhode Island in the Second Continental Congress, arriving just in time to vote for and sign the Declaration of Independence and remaining until 1785.

Monday, November 13, 2023

“Say, didst thou never practise such deceit?”

As I described yesterday, in March 1769 the British writer Horace Walpole asked Thomas Chatterton for more information about the fifteenth-century manuscript he said he was transcribing.

Chatterton’s 30 March reply included more verses and some remarks about his life as a poor young law clerk in Bristol, but no solid evidence. Walpole, born into wealth, became suspicious of a scam. He asked literary friends about the Rowley writings. They told him the language and form weren’t authentic.

On 4 April, Walpole sent Chatterton what he viewed as an avuncular letter, advising him to stick to his studies instead of literary forgeries. That document doesn’t survive.

Four days later, Chatterton replied, insisting that the Rowley writings were genuine. He also admitted he was “but 16 Years of Age.” And in a snit he wrote about “destroying all my useless Lumber of Literature, and never using my Pen again but in the Law.”

Then Chatterton sent another letter on 14 April, asking Walpole to return his manuscripts. This paper has a scrawled postscript: “Apprentice to an Attorney Mr Lambert, who is a Good Master; I find engrossing Mortgages &c a very irksome employ.”

Walpole went to France before returning the documents. That prompted even angrier demands from the teenager in July and August. On his return, Walpole wrote a response accusing Chatterton of “entertaining yourself at my expense” but decided not to send it. Instead, he just bundled up the Rowley papers and mailed them to Bristol.

At some point, and it’s unclear when, Chatterton summed up his feelings in a poem about Horace Walpole being mean, snobby, and hypocritical:

That fall, the young man turned to political writing using the name Decimus. In 1770 he left the attorney’s office and moved to London to establish a literary career. John Wilkes and other opposition politicians admired his essays, but no one paid him for them. He penned some more Rowley poems but couldn’t publish them, either.

On 24 Aug 1770 Chatterton killed himself by drinking arsenic. He was three months shy of turning eighteen. He was evidently a person of strong moods.

Seven years later, a scholar named Thomas Tyrwhitt collected some of Chatterton’s manuscripts and published Poems Supposed to have been Written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and Others, in the Fifteenth Century. He was among the shrinking number of people who thought the Rowley documents were genuine.

That book prompted articles about Chatterton, the supposed young discoverer. One detail in those reports was that Walpole had discouraged him. Indeed, a writer from Bristol said that Walpole’s dismissal had led to Chatterton’s suicide “soon after,” though a year had passed between the events.

But remember how Walpole owned a printing press? He could put out his side of the story. He printed a small private edition, enough to circulate among his many literary friends.

Meanwhile, Chatterton’s work, life, and death became yet another inspiration for the Romantics.

As a result, the exchange between Chatterton and Walpole is well known to scholars of literature and literary gossip. Some documents in their brief 1769 correspondence are already in libraries. Walpole’s early biographer, Mary Berry, had access to all the letters that survived in his papers and summarized them.

Now a few more of those documents—Chatterton’s letters, Walpole’s unsent reply, and his note on when he returned the Rowley writings—have come on the auction market. Bonhams is offering the collection for sale on 14 November. The estimated price is £100,000–150,000.

Chatterton’s 30 March reply included more verses and some remarks about his life as a poor young law clerk in Bristol, but no solid evidence. Walpole, born into wealth, became suspicious of a scam. He asked literary friends about the Rowley writings. They told him the language and form weren’t authentic.

On 4 April, Walpole sent Chatterton what he viewed as an avuncular letter, advising him to stick to his studies instead of literary forgeries. That document doesn’t survive.

Four days later, Chatterton replied, insisting that the Rowley writings were genuine. He also admitted he was “but 16 Years of Age.” And in a snit he wrote about “destroying all my useless Lumber of Literature, and never using my Pen again but in the Law.”

Then Chatterton sent another letter on 14 April, asking Walpole to return his manuscripts. This paper has a scrawled postscript: “Apprentice to an Attorney Mr Lambert, who is a Good Master; I find engrossing Mortgages &c a very irksome employ.”